Training and utilizing scent detection dogs in the identification of the European spruce bark beetle Ips typographus

Kangaslampi R., Tikkanen O.-P. (2026). Training and utilizing scent detection dogs in the identification of the European spruce bark beetle Ips typographus. Silva Fennica vol. 60 no. 1 article id 25022. https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.25022

Highlights

- Scent detection dogs can identify a small sample of live European spruce bark beetles with a 98% sensitivity in the laboratory

- Training a scent detection dog to detect bark beetles is relatively time-efficient

- Early intervention strategies may benefit from inclusion of scent detection dogs in the management process.

Abstract

The European spruce bark beetle (Ips typographus L.) thrives in weakened mature spruce (Picea abies (L.) H. Karst.) stands, causing massive destruction and becoming more abundant in Europe since the late 2010s. Early identification of new outbreaks is essential to ensure timely logging of infested trees to control the bark beetle population. Scent detection dogs (Canis lupus familiaris L.) are being used to identify illegal substances, diseases, and animal scat. In this study, the use of scent detection dogs in the identification of the European spruce bark beetle was tested. The main objective was to examine whether a dog could be trained to reliably identify the scent of a small group of live bark beetles. In this study we carried out comprehensive testing of the accuracy of the method in the laboratory and performed a small-scale functionality study in a field setting. The study was conducted by training two scent detection dogs to identify live bark beetles from empty samples and interference samples. This study differs from previous publications regarding spruce bark beetle detection, as our dogs were trained on live beetles. We concluded that, after a relatively short training period (23 days within eight weeks), scent detection dogs can identify a small sample of live European spruce bark beetles with a 98% sensitivity in the laboratory. The sensitivity was remarkably high and gave positive indications of the method’s functionality and usability in the future also in field conditions. The use of a scent detection dog can be a welcome and effective way to identify bark beetle damage.

Keywords

Ips typographus;

conservation detection dog;

scent detection dog;

spruce bark beetle, wildlife detection dog

-

Kangaslampi,

University of Eastern Finland; Faculty of Science, Forestry and Technology; P.O. Box 111, FI-80101 Joensuu, Finland

https://orcid.org/0009-0001-2965-3369

E-mail

reetta.kangaslampi@uef.fi

https://orcid.org/0009-0001-2965-3369

E-mail

reetta.kangaslampi@uef.fi

-

Tikkanen,

University of Eastern Finland; Faculty of Science, Forestry and Technology; P.O. Box 111, FI-80101 Joensuu, Finland

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3875-2772

E-mail

olli-pekka.tikkanen@uef.fi

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3875-2772

E-mail

olli-pekka.tikkanen@uef.fi

Received 6 August 2025 Accepted 17 January 2026 Published 23 January 2026

Views 4574

Available at https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.25022 | Download PDF

Supplementary Files

1 Introduction

The European spruce bark beetle (Ips typographus L. (Spruce bark beetle; Coleoptera: Curculionidae)) is considered to be the most economically significant forest pest of the Norway spruce (Picea abies (L.) H. Karst.; hereafter referred to as spruce) (Wermelinger 2004; Venäläinen et al. 2020). The spruce bark beetle thrives in weakened mature spruce stands, and can cause massive destruction in large, forested areas. Newly attacked trees show signs of boring holes, resin flow, discoloration and eventually visible bark damage. Due to the changing climate, pest insects are becoming increasingly prominent, broadening their range drastically (Battisti and Larsson 2015). Attack risk is related to the nutrient and water supply of the trees (Wermelinger 2004; Netherer et al. 2019), and due to increasing temperatures, conditions have become more favorable to spruce bark beetle outbreaks in Northern Europe (Tikkanen and Lehtonen 2023). In Finland, though the scale of damage has for now remained less significant compared to the Central Europe (Hantula et al. 2023), spruce bark beetle outbreaks have become more abundant since the late 2010s (Hantula et al. 2023; Tikkanen and Lehtonen 2023). Due to these progressing concerns, there is an immense need to further develop new practices for mapping and controlling spruce bark beetle outbreaks (Pulgarin Diaz et al. 2024). To decrease the risk of outbreaks spreading further, it is important that infested trees are removed swiftly (Hlásny et al. 2021). To ensure success, this sanitation logging should be done immediately after the infestation, before new spruce bark beetle adults emerge from the spruce trees (Pulgarin Diaz et al. 2024). Humans are unable to visually note very early infestations, which leads to complications in identifying new outbreaks and being able to act promptly (Johansson et al. 2019).

Professionally trained scent detection dogs (also known as conservation detection dogs) are specifically trained to detect a certain odor. The olfactory capabilities of dogs are central to their success in working together with humans (Serpell 2016). Humans have six million olfactory receptor cells, whereas sheepdog noses have more than 200 million, and beagle noses over 300 million (Horowitz 2009), allowing them to detect specific scents in a variety of environmental conditions (DeMatteo et al. 2019). This extraordinary olfactory ability is harnessed in conservation detection to locate species in the wild, such as endangered plants, mammals, and birds, or to detect the presence of invasive species (DeMatteo et al. 2019). This non-invasive method is often more efficient and less costly than traditional methods like camera traps or direct observation, especially in dense or inaccessible terrain (Dahlgren et al. 2012; Bennett et al. 2019).

Despite their remarkable capabilities, the use of scent detection dogs in species identification is not without challenges. Training these dogs requires significant resources and expertise, as the process can be lengthy and expensive (DeMatteo et al. 2019). Furthermore, dogs must be carefully matched to the environment and task, as different species and ecosystems present unique challenges (DeMatteo et al. 2019). Previously, dogs have been trained to detect spruce bark beetle pheromones by utilizing synthetic semiochemicals (Johansson et al. 2019; Vošvrdová et al. 2023). Dogs have also been trained to detect other elusive insects like termites (Brooks et al. 2003), bed bugs (Pfiester et al. 2008), palm weevils (Suma et al. 2014) and endangered Coleoptera (Mosconi et al. 2017).

The purpose of this study was to investigate and describe a new, not much researched tool for detecting spruce bark beetles. We wanted to establish whether scent detection dogs could be trained to detect live spruce bark beetles in a laboratory setting within a relatively short three-month training period. The main research questions were how sensitive a trained dog would be to the scent of a small group of live bark beetles, how quickly could the training be done without compromising accuracy, and could the method be transferred into a real forest setting.

2 Methods

2.1 Dog selection

Two dogs were selected for the study, an 8-year-old spayed female medium German spitz (Dog A), and a 2-year-old intact male volpino italiano (Dog B). Both dogs represented spitz-type breeds, which is uncommon but not unheard of in scent detection use (Grimm-Seyfarth et al. 2021). There are three groups of breeds most often utilized in species detection: sheepdogs and cattledogs, pointers and setters, and retrievers, flushing dogs and water dogs (Grimm-Seyfarth et al. 2021). While dog selection is crucial for the success of a study (DeMatteo et al. 2019), we considered our study approach to be executable with a variety of breeds. Dog selection poses additional challenges regarding housing the dogs and where to place the dogs after a study is finished (DeMatteo et al. 2019), but our choice enabled us to work with dogs we were already familiar with. The dogs had no previous experience in scent detection, but they were well-established sport dogs, allowing them to be very trainable and enthusiastic. The dogs had been training and competing in other dog sports like agility and obedience, and had therefore a lot of training experience outside of scent detection.

2.2 Material storage and handling

Spruce bark beetle adults were collected using pheromone traps (baited with Ipsowit® lures). To ensure variability in sample scents, pheromone traps were placed in three different locations (furthest ones being 467 km apart): Kontiolahti in the province of North Karelia (62°44´N, 29°55´E); Tampere (61°28´N, 23°45´E) and Sastamala (61°20´N, 22°55´E), in the province of Pirkanmaa. Some spruce bark beetles were collected also by hand straight from the tree bark. All beetles were collected from late May to early June. The was a large-scale ongoing epidemic at the time of collection on all three collection sites. All collection sites were mature spruce dominated forests. The beetles were handled with boiled tweezers to eliminate handler scent. All spruce bark beetle material was stored in labeled glass containers in +4 °C, allowing the beetles to stay alive for the duration of the study. After the study was finished, the beetles were euthanized by freezing.

Glass containers (128 cm3) with metallic lids were used in the study (Fig. 1). The lids had small air holes in them, allowing scent to pass through, but preventing the dogs from touching the spruce bark beetles or other material. During testing, the containers were placed into opaque ceramic holders, to avoid any visual cues for the dogs. After each test, the containers were boiled and dried out to ensure no residual odor is left.

Fig. 1. Dog A performs the final indication on the bark beetle target container. Bark beetles are visible for illustrative purposes.

2.3 Outlines of the training and testing process

The dogs were trained using positive reinforcement. Positive reinforcement is a reward-based training technique, and it is an effective way to promote learning in scent detection (Hurt and Smith 2009; Johnen et al. 2013). In this study, mainly food rewards were used during initial training, but occasionally also play-time (tug or ball). Our goal was to complete the training process within three months, allowing some room for error in case of difficulties. Eventually, the training period was eight weeks (23 training days), and it was split into three phases: imprinting phase, training phase and pre-testing phase. Each dog was trained three times per week.

During the imprinting phase, the dogs were trained to associate spruce bark beetle odor with food. When imprinting a dog on a new odor, the dog must learn that the recognition of this specific odor is linked to a reward (Johnen et al. 2013). The dogs were trained directly on the target smell, although synthetic pheromones had been used in previous studies on spruce bark beetle identification (Johansson et al. 2019; Vošvrdová et al. 2023). Training on live beetles was chosen out of interest, one of the research questions being whether dogs could be trained directly on live insects instead of synthetic pheromones. During the imprinting phase, the dog was allowed to sniff only one individual container (spruce bark beetles inside) and was immediately rewarded with food. A clicker was used as an aid to mark the correct action for the dog. A clicker is a device used in dog training that emits a double-click sound and can be used as an additional tool to give the dog a positive secondary reinforcement when the handler is further away, before the actual food reward (Smith and Davis 2008).

Separately, the dogs were trained to perform a final alerting task called an “indication” (Fig. 1). Dog A was trained to indicate the correct odor source by lying on the ground. Dog B was trained to touch the right container with his left front paw. The methods of indication were chosen according to the dogs’ own willingness and were trained using food. When moving to the next phase the dogs already knew the indication behavior.

After the imprinting phase, the training proceeded to the training phase. During the training phase, the dog learned to discriminate between the target odor and interference (distracting, incorrect) odors, and to perform the final indication on the target odor. In the training phase, the dog was cued to search along a lineup-setting of containers, one of which contained the target odor (spruce bark beetle), and the others being empty. The training phase was conducted as non-blind: the handler knew which choice was correct. The training phase was continued until both dogs presented over 75% correct indications on the ten-option lineup. This happened within 11 training days for both dogs.

During the pre-testing phase, the dogs were trained on a ten-option lineup, mimicking the test setting. Interference odors were presented in the setting, to ensure the dogs had learned the precise target odor. Spruce needles, tree bark, animal fur, dog food and wood chippings were used as interference odors. The pre-testing phase was continued until both dogs showed 100% sensitivity (percentage of correct positives of all positives) during two training sessions, on a ten-option lineup with one target odor and two interference odors.

The final testing phase consisted of 11 testing days, during which the dogs were tested a total of 100 rounds. Dog A was tested on nine days, dog B 11 days, each dog performed 5 test runs during one testing day. The testing phase was carried out by two people (dog handler and research assistant) to enable the tests to be carried out as double blind tests (dog handler does not know which option is correct, research assistant is not present in the room). This eliminated the risk of the dog handler giving unconscious clues to the dog, which improves the reliability and repeatability of the testing process. The test setting consisted of a ten-option line-up: ten containers were placed side-by-side on the floor in ceramic opaque containers to avoid any visual clues (Fig. 2). Each arrangement presented one correct option, one interference sample (tree bark, spruce needles, dog food, animal fur), and eight empty containers. The research assistant placed the containers in a random order, each container numbered (1–10), whilst the handler waited outside the laboratory room. After each test, the handler noted the indicated container number to the assistant, who then confirmed (correct/not correct). The dog and handler were removed from the room after each test round, to avoid handler interference. Each testing day consisted of five test runs per dog. All indications were marked down.

Fig. 2. During the bark beetle detection testing phase, the glass containers were placed into opaque containers to eliminate any visual clues for the dog or the handler.

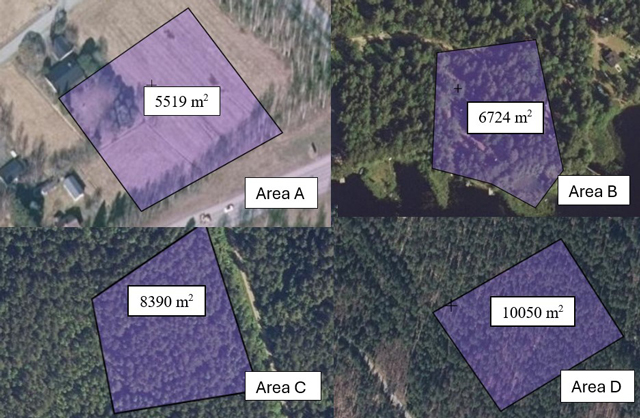

After the initial laboratory tests, the dogs were tested in an outdoor setting. Outdoor testing phase focused on indicating on targets higher up (in a tree, Fig. 3) and searching larger areas. After two weeks (eight training sessions for both dogs) of transferring the search skill into a woodland setting, the dogs’ skills were tested in the field to more reliably assess future research opportunities. Four field sites were chosen, three of which being mature spruce-dominated forest stands, typical for bark beetle damage, one being a grassy field area surrounded by some trees (Fig. 4). Spruce bark beetles were hidden in trees at the height of 0–2 meters, using glass vials. At this stage, the dogs’ skills were evaluated by observing and reporting. We performed 12 testing days, four for dog A and eight for dog B. The size of the search area was 0.5–1 hectares, and each test run had 1–3 pre-hidden targets of spruce bark beetle. Three empty vials were hidden in each test. Each target vial contained about 20 live spruce bark beetle individuals. When hiding target vials and empty vials, the test assistant would walk around the study site and randomly touch additional trees to ensure the dogs can’t just follow human scent to the vials. During one testing day, we performed 2–3 testing runs. The purpose of the small-scale field study was to collect data for larger field-testing opportunities in the future, and to ensure the skills of the dogs were transferable from the laboratory setting to a forest or field area.

Fig. 3. Dog B indicating on a bark beetle target placed into a spruce tree during the field tests on area C.

Fig. 4. Area A field-type test site, urban area, Area B forested test site, Area C forested test site, and Area D forested test site. Terrain information and Creative Commons Licence CC BY-SA 4.0, © Maanmittauslaitos, 1/2025.

2.4 Data analysis

During each day of the testing phase, the numbers of correct positive, correct negative, false-positive and false-negative indications were counted. These values characterize testing success in scent detection. From the results of the test rounds, the following three indicators were calculated: (1) Sensitivity = number of correctly identified positives/total number of positive samples × 100, (2) Specificity = number of correctly identified negatives/total number of negative samples × 100, and (3) Accuracy = number of correctly identified positives + correctly identified negatives/all samples.

To analyze data relevance, we performed two non-parametric binomial tests (laboratory results, field test results). Additionally, the difference between dogs’ performances in the laboratory was analyzed using a Mann-Whitney U-test. The statistical program used was IBM SPSS Statistics 27.

3 Results

We found that after 23 days of training, during 11 testing days (Table 1), scent detection dogs could identify a small (less than 10 individuals) group of spruce bark beetles effectively. In laboratory setting, the choice of correct indication of spruce bark beetles by dogs was not random (binominal test, n = 100, p < 0.0001), with a 98% (S.D. 3.86%) sensitivity (Table 2). Although the performance of Dog B was slightly better than Dog A (A identified correctly 43/45, B 55/55), the difference between the dogs was not significant (Mann & Whitney U = 38.5, p = 0.42). Overall specificity was 99.8% and accuracy was 99.6% (Table 2).

| Table 1. Schedule and results of the scent detection dog testing phase of spruce bark beetle detection in laboratory conditions. Dogs were tested on a blind trial, ten-option line-up setting. Dog A participated in nine testing days, dog B in 11 testing days. | ||||

| Date | Correct positives/ total positives (Dog A) | Correct negatives / total negatives (Dog A) | Correct positives/ total positives (Dog B) | Correct negatives/ total negatives (Dog B) |

| 27.7.2022 | - | - | 5/5 | 45/45 |

| 29.7.2022 | - | - | 5/5 | 45/45 |

| 1.8.2022 | 5/5 | 45/45 | 5/5 | 45/45 |

| 3.8.2022 | 5/5 | 45/45 | 5/5 | 45/45 |

| 9.8.2022 | 5/5 | 45/45 | 5/5 | 45/45 |

| 13.8.2022 | 5/5 | 45/45 | 5/5 | 45/45 |

| 15.8.2022 | 4/5 | 44/45 | 5/5 | 45/45 |

| 19.8.2022 | 4/5 | 44/45 | 5/5 | 45/45 |

| 20.8.2022 | 5/5 | 45/45 | 5/5 | 45/45 |

| 29.8.2022 | 5/5 | 45/45 | 5/5 | 45/45 |

| 2.9.2022 | 5/5 | 45/45 | 5/5 | 45/45 |

| Overall | 43/45 | 403/405 | 55/55 | 495/495 |

| Table 2. Spruce bark beetle detection sensitivity, specificity and accuracy (n = 100) in the scent detection dog laboratory testing phase. | |||||||

| Spruce bark beetle detection | n | Sensitivity | Specificity | Accuracy | |||

| Mean | S.D. | Mean | Correct 1 | Mean | Correct 2 | ||

| Dog A | 45 | 95.6% | ±8.31% | 99.5% | 403/405 | 99.1% | (43+403)/450 |

| Dog B | 55 | 100% | ±0,00% | 100% | 495/495 | 100% | (55+495)/550 |

| Overall | 100 | 98.0% | ±3.86% | 99.8% | 898/900 | 99.6% | (98+898)/1000 |

| 1 correct negatives/all negatives × 100 2 correct positives+correct negatives/all samples × 100 | |||||||

During the field tests, dogs were able to detect hidden vials of spruce bark beetle adults with a sensitivity of 85.2% (Table 3). Sensitivity did not differ significantly between dogs (dog A 85.7%, dog B 85.0%); however, dog A was tested only on four days, dog B on eight days. Bark beetle detection and indication in an outdoor setting was not random (binominal test, n = 54, p < 0.0001).

| Table 3. Results of field tests where the abilities of laboratory trained dogs to detect spruce bark beetles in natural conditions were evaluated. Dogs were tested on 12 days, on four different field sites. Each day consisted of two or three test runs; 1–3 targets were hidden for each run. One dog was tested per day. | ||||

| Date | Field site, location, area | Total number of targets per day | Finds (correct positives) | Dog |

| 5.6.2023 | A, Sastamala; 5519 m2 | 2 | 2 | A |

| 3.7.2023 | A, Sastamala; 5519 m2 | 3 | 3 | B |

| 15.7.2023 | A, Sastamala; 5519 m2 | 5 | 4 | A |

| 28.7.2023 | B, Urjala; 6724 m2 | 6 | 6 | B |

| 29.7.2023 | B, Urjala; 6724 m2 | 8 | 7 | B |

| 5.8.2023 | A, Sastamala; 5519 m2 | 4 | 3 | A |

| 12.8.2023 | C, Huittinen; 8390 m2 | 4 | 4 | B |

| 14.8.2023 | B, Urjala; 6724 m2 | 5 | 4 | B |

| 16.8.2023 | A, Sastamala; 5519 m2 | 3 | 3 | A |

| 4.9.2023 | D, Sastamala; 10050 m2 | 4 | 2 | B |

| 5.9.2023 | D, Sastamala; 10050 m2 | 4 | 3 | B |

| 11.9.2023 | B, Urjala; 6724 m2 | 6 | 5 | B |

| Total sum | 54 | 46 | ||

| Overall sensitivity 1 | 85.2% | |||

| 1 Correct positives/all positives × 100 | ||||

4 Discussion

Our study demonstrated the proficient usability of scent detection dogs in identifying small groups of spruce bark beetles. Our results show a remarkable 98% sensitivity under laboratory conditions, which is in accordance with other similar studies. In comparison, other studies have proved detection dogs to be able to identify beetles or associated scents with a sensitivity of 84% (Osmoderma eremita scent infiltrated paper, Mosconi et al. 2017), 73.3–100% (Anoplophora glabripennis and Anolophora chinensis, Hoyer-Tomiczek and Hoch 2020), and 99% (Ips typographus synthetical semiochemicals, laboratory setting, Johansson et al. 2019). Accuracy was not mentioned in some studies, as sensitivity is a more direct measure in identifying correct positives in a laboratory setting.

Accuracy of trained dogs in our study was also excellent, 99.6%. Johansson et al. (2019) reported that their dogs did not sample (sniff) all presented containers, which resulted in lower correct negatives (specificity) and thus lower accuracy. In our study, the dogs sampled all odor containers, resulting in high accuracy. This does not directly correlate between dogs’ skills but is more due to differences in training strategies.

In our study, the dogs were trained in only 23 days before the testing phase, during the period of eight weeks (three times per week). Few previous studies report the duration of training before testing dogs. Suma et al. (2014) reported a training period of three months with inexperienced dogs, thrice weekly, which is of similar duration. Johnen et al. (2013) suggested that the duration of scent detection dog training could vary between 7 days and 16 months, depending on the experience level of the dog. While the basic training period can be only 1–3 months, the subsequent discrimination phase can last up to 6 or 7 months (Suma et al. 2014; Hoyer-Tomiczek et al. 2016). Our study also shows that dogs can be trained directly on live spruce bark beetles, which differs from previous studies (e.g. Johansson et al 2019). Regarding other species, however, there are indications of successful training directly on insects (e.g. Suma et al. 2014; Hoyer-Tomiczek and Hoch 2020).

Although the number of dogs used in this study and the test settings were limited, the results are extremely encouraging. During small-scale field tests, the dogs found hidden spruce bark beetle targets with an 85% sensitivity. In relation to other publications (but different beetle species), our results appear similar. Hoyer-Tomiczek and Hoch (2020) reported a 73% sensitivity in a field-setting, Mosconi et al (2017) 69% in difficult terrain. Our field study was limited and was only intended as a pilot test to offer insight into performing a larger study in the future. Dog A participated in only four testing days, due to feeling under the weather in September, so mainly dog B was tested. During the initial field tests, we could purposefully plan for future large-scale field tests, to ensure method functionality in a real-life scenario. However, the field test successfully achieved its main purpose, which was to confirm that the dogs’ skills were transferable into a more demanding setting, outside of a laboratory room.

It can be concluded that scent detection dogs could be used in early identification of spruce bark beetles, especially as an additional tool to complement visual inspection or remote sensing methods. Remote sensing techniques can be useful in forest canopy mortality assessments (Junttila et al. 2024; Turkulainen et al. 2025) but lack the timely accuracy of terrestrial surveys (Kautz et al. 2024). Remote sensing can therefore be an important tool to complement terrestrial surveys but cannot currently fully replace them (Kautz et al. 2024), which highlights the need for other options. Dogs’ main advantage compared to humans is search speed and accuracy (Johansson et al. 2019; Vošvrdová et al. 2023). Currently, the “search and pick” method of removing infested trees by sanitation logging within 2–3 weeks of attack seldom succeeds (Svensson 2007) due to timing errors and unclear identification of new infestations. Utilizing scent detection dogs can help pinpoint the colonized trees at the exact time of infestation, thus enabling acting more swiftly. A more timely risk assessment would enhance workflow and management efficacy (Kautz et al. 2024).

This study indicates that scent detection dogs can be a versatile, effective and welcome addition to the toolbox of forest owners and managers to tackle the problem that bark beetles cause to forest health. Though detection dog training requires expertise and time investment, it does not appear to be too demanding or excessively expensive, in comparison to its possibilities in avoiding huge financial losses in silviculture.

Further experiments should be carried out to confirm the usability and efficiency of the method in a larger forest setting over a longer time period. Sample placement at different heights should be studied and evaluated due to its relevance to a natural spruce bark beetle detection situation. The training method described in this study is not only suitable for detecting spruce bark beetles, but it can also be used to train dogs to detect a variety of other forest pests, including invasive alien species.

Declaration of openness of research materials, data, and code

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available by open access in data repository Zenodo: https://zenodo.org/records/16751767.

Ethical review

All applicable Finnish ethic guidelines regarding the care and use of animals were followed. The dogs were trained utilizing only positive reinforcement techniques. Both dogs participating in this study were owned privately by one of the authors and handled by their owner. As the dogs were not considered laboratory animals, their participation did not require specific licensing.

Authors’ contributions

R.K. and O-P.T. designed research; R.K. collected data; R.K. and O-P.T. analyzed data; all authors contributed to the writing process; all authors read and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgements

We thank Tiina Ylioja for her valuable comments regarding this manuscript. We would also like to thank all funding agencies, landowners, University of Eastern Finland, Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke), Äetsän Seudun Koirakerho, Tampereen Seudun Koirakerho, K9 Conservationists/Kayla Fratt for all your widely shared knowledge, testing assistant Sami Pursiainen, and especially scent detection dogs Lumo (A) and Loitsu (B), without whom none of this could have been possible.

Funding

This work was supported with a personal working grant for author R.K. by the Finnish Cultural Foundation (Suomen Kulttuurirahasto), with supplies grants from the Finnish Forest Association (Suomen Metsäsäätiö), Huittisten Säästöpankkisäätiö, Suodenniemen Säästöpankkisäätiö, and travel support from Jouko Tuovolan säätiö, and by the Research Council of Finland (former Academy of Finland) [grant numbers 337127 and 357906 for UNITE flagship].

Financial interests: Author R.K. has received research funding and supply funding from the above-mentioned agencies. Author O-P.T. has no relevant financial interests regarding this paper.

References

Battisti A, Larsson S (2015) Climate change and insect pest distribution range. In: Björkman C, Niemela P (eds) Climate change and insect pest. CABI International, Wallingford, pp 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1079/9781780643786.0001.

Bennett EM, Hauser CE, Moore JL (2019) Evaluating conservation dogs in the search for rare species. Conserv Biol 34: 314–325. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13431.

Brooks SE, Oi FM, Koehler PG (2003) Ability of canine termite detectors to locate live termites and discriminate them from non-termite material. J Econ Entomol 96: 1259–1266. https://doi.org/10.1603/0022-0493-96.4.1259.

Dahlgren DK, Elmore RD, Smith DA, Hurt A, Arnett EB, Connelly JW (2012) Use of dogs in wildlife research and management. In: Silvy NJ (ed) The wildlife techniques manual, 7th ed. The John Hopkins University Press, pp 140–153.

DeMatteo KE, Davenport B, Wilson LE (2019) Back to the basics with conservation detection dogs: fundamentals for success. Wildl Biol 2019, article id 00584. https://doi.org/10.2981/wlb.00584.

Grimm-Seyfarth A, Harms W, Berger A (2021) Detection dogs in nature conservation: a database on their world-wide deployment with a review on breeds used and their performance compared to other methods. Methods Ecol Evol 12: 568–579. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13560.

Hantula J, Ahtikoski A, Honkaniemi J, Huitu O, Härkönen M, Kaitera J, Koivula M, Korhonen KT, Lindén A, Lintunen J, Luoranen J, Matala J, Melin M, Nikula A, Peltoniemi M, Piri T, Räsänen T, Sorsa J-A, Strandström M, Uusivuori J, Ylioja T (2023) Metsätuhojen kokonaisvaltainen arviointi: METKOKA-hankkeen loppuraportti. [Comprehensive assessment of forest destruction: final report of the METKOKA project]. Natural resources and bioeconomy studies 46/2023, Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke). http://urn.fi/ URN:ISBN:978-952-380-688-7.

Hlásny T, König L, Krokene P, Lindner M, Montagné-Huck C, Müller J, Qin H, Raffa KF, Schelhaas MJ, Svoboda M, Viiri H (2021) Bark beetle outbreaks in Europe: state of knowledge and ways forward for management. Curr For Reports 7: 138–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s40725-021-00142-x.

Hoffmann BD, Faulkner C, Brewington L, Lawton F (2022) Field quantifications of probability of detection and search patterns to form protocols for the use of detector dogs for eradication assessments. Ecol Evol 12, article id e8987. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.8987.

Hoyer-Tomiczek U, Sauseng G, Hoch G (2016) Scent detection dogs for the Asian longhorn beetle, Anoplophora glabripennis. EPPO Bull 46: 148–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/epp.12282.

Hoyer-Tomiczek U, Hoch G (2020) Progress in the use of detection dogs for emerald ash borer monitoring. Forestry 93: 326–330. https://doi.org/10.1093/forestry/cpaa001.

Hurt A, Smith DA (2009) Conservation dogs. In: Helton WS (ed) Canine ergonomics. The science of working dogs. Taylor & Francis Group, pp 175–194. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781420079920.ch9.

Johansson A, Birgersson G, Schlyter F (2019) Using synthetic semiochemicals to train canines to detect bark beetle–infested trees. Ann For Sci 76, article id 58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-019-0841-z.

Johnen D, Heuwieser W, Fischer-Tenhagen C (2013) Canine scent detection – fact or fiction? Appl Anim Behav Sci 148: 201–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2013.09.002.

Junttila S, Blomqvist M, Laukkanen V, Heinaro E, Polvivaara A, O’Sullivan H, Yrttimaa T, Vastaranta M, Peltola H (2024) Significant increase in forest canopy mortality in boreal forests in Southeast Finland. For Ecol Manag 565, article id 122020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2024.122020.

Kautz M, Feurer J, Adler P (2024) Early detection of bark beetle (Ips typographus) infestations by remote sensing – a critical review of recent research. For Ecol Manag 556, article id 121595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2023.121595.

Mosconi F, Campanaro A, Carpaneto GM, Chiari S, Hardersen S, Mancini E, Maurizi E, Sabatelli S, Zauli A, Mason F, Audisio P (2017) Training of a dog for the monitoring of Osmoderma eremita. Nat Conserv 20: 237–264. https://doi.org/10.3897/natureconservation.20.12688.

Netherer S, Panassiti B, Pennerstorfer J, Matthews B (2019) Acute drought is an important driver of bark beetle infestation in Austrian Norway spruce stands. Front For Glob Change 2, article id 39. https://doi.org/10.3389/ffgc.2019.00039.

Pfiester M, Koehler PG, Pereira RM (2008) Ability of bed bug-detecting canines to locate live bed bugs and viable bed bug eggs. J Econ Entomol 101: 1389–1396. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/101.4.1389.

Pulgarin Diaz JA, Melin M, Ylioja T, Lyytikäinen-Saarenmaa P, Peltola H, Tikkanen OP (2024) Relationship between stand and landscape attributes and Ips typographus salvage loggings in Finland. Silva Fenn 58, article id 23069. https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.23069.

Serpell J (ed) (2016) The domestic dog: its evolution, behavior and interactions with people, 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139161800.

Smith SM, Davis ES (2008) Clicker increases resistance to extinction but does not decrease training time of a simple operant task in domestic dogs (Canis familiaris). Appl Anim Behav Sci 110: 318–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2007.04.012.

Suma P, La Pergola A, Longo S (2014) The use of sniffing dogs for the detection of Rhynchophorus ferrugineus. Phytoparasitica 42: 269–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12600-013-0330-0.

Svensson L (2007) Övervakning av insektsangrepp – slutrapport från Skogsstyrelsens regeringsuppdrag. [Monitoring of insect attacks – final report from SFA’s government assingment]. Swedish Forest Agency. http://shop.skogsstyrelsen.se/shop/9098/art73/4645973-904329-1557-1.pdf.

Tikkanen O, Lehtonen I (2023) Changing climatic drivers of European spruce bark beetle outbreaks: a comparison of locations around the Northern Baltic Sea. Silva Fenn 57, article id 23003. https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.23003.

Turkulainen E, Hietala J, Jormakka J, Tuviala J, de Oliveira RA, Koivumäki N, Karila K, Näsi R, Suomalainen J, Pelto-Arvo M, Lyytikäinen-Saarenmaa P, Honkavaara E (2025). Towards scalable wide area UAS monitoring of forest disturbance using hydrogen powered airships. Int J Remote Sens 46: 177–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/01431161.2024.2399327.

Venäläinen A, Lehtonen I, Laapas M, Ruosteenoja K, Tikkanen OP, Viiri H, Ikonen V, Peltola H (2020) Climate change induces multiple risks to boreal forests and forestry in Finland: a literature review. Glob Chang Biol 26: 4178–4196. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15183.

Vošvrdová N, Johansson A, Turčáni M, Jakuš R, Tyšer D, Schlyter F, Modlinger R (2023) Dogs trained to recognise a bark beetle pheromone locate recently attacked spruces better than human experts. For Ecol Manag 528, article id 120626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2022.120626.

Wermelinger B (2004) Ecology and management of the spruce bark beetle Ips typographus – a review of recent research. For Ecol Manag 202: 67–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2004.07.018.

Total of 29 references.