Is it possible to extend the season for direct seeding of Scots pine and lodgepole pine in northern Fennoscandia?

Hyppönen M., Hallikainen V., Bergsten U., Winsa H., Miina J., Valkonen S., Helenius P., Jaskari E., Rautio P. (2025). Is it possible to extend the season for direct seeding of Scots pine and lodgepole pine in northern Fennoscandia? Silva Fennica vol. 59 no. 3 article id 24064. https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.24064

Highlights

- Scots pine and lodgepole pine were direct seeded during June–November in a six-year experiment in Finnish Lapland

- Both early summer and late autumn as well as early winter were appropriate periods for the successful seeding of both species

- Seeding in late summer and early autumn (August and September) was much less successful for Scots pine

- For lodgepole pine seeding time, site quality or cold-wet treatment of seeds were not critical for the seedling emergence or survival.

Abstract

The aim of this study was to experimentally test the most favourable seeding times for Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.), and to compare Scots pine and lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta Douglas ex Loudon) in respect to suitable seeding times and site factors. The experimental area was located in Sodankylä, Central Finnish Lapland. Generalized linear mixed effects models with binomial distribution assumption were applied to model the presence or absence of a seedling at a seeding point. The study shows that in addition to spring and early summer, direct seeding of Scots pine can also be carried out during late autumn or even early winter (October and November) in northern Fennoscandia. On the contrary, seeding in late summer and early autumn (August and September) is much less successful and cannot be recommended as such, but can be used if the amount of seeding material is increased to compensate the loss. There is more flexibility for lodgepole pine for which the proper seeding period seems to be from spring through to late autumn. Whether lodgepole pine seeds were stratified or not had no statistically significant effect on regeneration success. Our results clearly indicate that lodgepole pine is less susceptible to unfavourable site and soil factors than Scots pine. Our results give support to extend the period of direct seeding from the present early summer to another period in late autumn and even early winter.

Keywords

Pinus sylvestris;

Pinus contorta;

artificial regeneration;

autumn direct seeding;

generalized linear mixed effects models

- Hyppönen, Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke), Ounasjoentie 6, FI-96200 Rovaniemi, Finland E-mail mikkokthypponen@gmail.com

-

Hallikainen,

Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke), Ounasjoentie 6, FI-96200 Rovaniemi, Finland

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5384-8265

E-mail

ext.ville.hallikainen@luke.fi

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5384-8265

E-mail

ext.ville.hallikainen@luke.fi

- Bergsten, Department of Forest Biomaterials and Technology, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU), Skogsmarksgränd, SE-901 83 Umeå, Sweden E-mail burskog@gmail.com

- Winsa, Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke), Ounasjoentie 6, FI-96200 Rovaniemi, Finland E-mail hans.winsa@gmail.com

-

Miina,

Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke), Yliopistokatu 6 B, FI-80100 Joensuu, Finland

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8639-4383

E-mail

jari.miina@luke.fi

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8639-4383

E-mail

jari.miina@luke.fi

-

Valkonen,

Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke), Latokartanonkaari 9, FI-00790, Helsinki, Finland

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2879-4821

E-mail

sauli.valkonen@luke.fi

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2879-4821

E-mail

sauli.valkonen@luke.fi

- Helenius, Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke), Tietotie 4, FI-31600 Jokioinen, Finland E-mail psjhelenius@elisanet.fi

- Jaskari, Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke), Ounasjoentie 6, FI-96200 Rovaniemi, Finland E-mail ejaskari@gmail.com

-

Rautio,

Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke), Ounasjoentie 6, FI-96200 Rovaniemi, Finland

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0559-7531

E-mail

pasi.rautio@luke.fi

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0559-7531

E-mail

pasi.rautio@luke.fi

Received 9 February 2025 Accepted 1 November 2025 Published 4 December 2025

Views 24381

Available at https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.24064 | Download PDF

Supplementary Files

1 Introduction

Direct seeding is a common method of regeneration of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) in the northern parts of Fennoscandia, in addition to natural regeneration and planting. Direct seeding is regularly used on xeric and sub-xeric upland forest sites. In the northern parts of Fennoscandia, it is also used on mesic upland sites with medium-coarse soil texture (Hyppönen and Karvonen 2005; Keskimölö et al. 2007; Bergsten and Sahlén 2013; Äijälä et al. 2019). In direct seeding, site preparation such as disc trenching or patching is always used to create suitable seeding spots and increase seed germination and survival rate. In Finland, direct seeding usually means seeding of Scots pine, while in Sweden both Scots pine and lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta Douglas ex Loudon) are regenerated by direct seeding (Beckman and Nilsson 2014).

Seeding has many advantages over natural regeneration, such as the possibility to use genetically, physiologically and technically improved material, to select a favourable seeding time and a suitable seeding spot, as well as independence from seed trees and seed crops. Compared to planting, the advantages are lower costs, higher seedling density and easier mechanisation (Bergsten and Sahlén 2013; Ersson 2021). The disadvantage of direct seeding is less control over spacing and number of seedlings, and the number of seeds sown must be based on expected germination and survival.

According to numerous previous studies, spring and early summer have been shown to be the biologically optimal times for seeding Scots pine in Finland and Sweden (Pohtila and Pohjola 1985; Kinnunen 1992; Winsa and Sahlén 2001; de Chantal et al. 2003; Bergsten and Sahlén 2013; Lundström 2015). In natural regeneration processes, most Scots pine seeds are released from the cones in May and June (Heikinheimo 1937; Hannerz et al. 2002). Therefore, until 2010, spring and early summer were the only recommended periods for direct seeding of Scots pine in management guidelines and textbooks in Finland and Sweden (Hokajärvi 1997; Hyppönen and Karvonen 2005; Keskimölö et al. 2007; Bergsten and Sahlén 2008). In Sweden, the recommendations for lodgepole pine are slightly different. In the recommendations of the Swedish Forest Agency (the national authority responsible for forestry issues in Sweden), direct seeding of lodgepole pine in the autumn is considered feasible because its seeds are naturally adapted to overwinter in the soil (Bergsten and Sahlén 2008, 2013; Ersson 2021).

The need to reduce regeneration costs has led to increased use of direct seeding compared to planting. Mechanised seeding has proven to be a highly operational and cost-effective method (Wennström et al. 1999; Hyppönen 2000; Kinnunen 2003; Miina and Saksa 2008). Since the 1990s, direct seeding in Finland has mainly been carried out mechanically in connection with site preparation, especially with disc trenching (Hyppönen 2000; Rummukainen et al. 2011; Hallongren et al. 2012). Currently about 80% of the area seeded for pine in Finland is carried out mechanically (Kulju et al. 2023).

There is a major operational problem with mechanical direct seeding in connection with site preparation. Site preparation machinery needs to be operated throughout the summer and autumn in order to be cost-effective and profitable for the contractor. In this sense, the direct seeding season in spring and early summer is very short. Additionally, the weighty site preparation and seeding equipment cannot be driven to a regeneration area until soil frost has melted, soil has drained, and its carrying capacity has been restored (Kinnunen 1996; Hyppönen 2000; Hyppönen and Karvonen 2005). By then, the biologically optimal seeding period has often passed. This has led to various alternative trials and practices to extend the seeding season.

In Finland, some practitioners have applied direct seeding throughout the summer, although according to many research results, the success of seeding in late summer (July and August) has produced the most unsatisfactory results (Heikinheimo 1940; Kangas 1940; Kinnunen 1992; de Chantal et al. 2003; Nygren 2011). In Sweden, late summer (July and August) is not considered a reliable and recommendable alternative either (Hedemann-Gade 1927; Bergsten and Sahlén 2013; Ersson 2021). An alternative, seeding in early autumn (September) after a summer break, has also not been encouraging (Heikinheimo 1940; Kinnunen 1992, 1996).

In Finnish Lapland, Metsähallitus (the state enterprise that administers state-owned land and water areas in Finland) applied direct seeding of Scots pine in late autumn (October and later) on experimental basis but quite extensively for about a decade (1997–2005). The basis for the large-scale trial was the fact that in some older studies (Hedemann-Gade 1927; Kangas 1940; Kinnunen 1982; but cf. Kinnunen 1992) the results of direct seeding in late autumn, in October and November, were quite promising, especially in the northern parts of Fennoscandia (Wibeck 1927). Another reason was that many observations from northern Fennoscandia suggest that pine seeds can survive for several years in the surface layers of the soil (Renvall 1912; Lassila 1920; Wikström 1922; Sirén 1952). Such post-germination may play a significant role in natural forest regeneration under harsh climatic conditions, to some extent for Scots pine (Lassila 1920; Sirén 1952; Häggman 1987; Tillman-Sutela 1995), but especially for lodgepole pine (Solbraa and Andersen 1997; Varmola et al. 2000).

The regeneration areas in the autumn seeding trial of Metsähallitus mentioned above were inventoried in 2008. In this trial, there was an average of 7000 seedlings ha–1, excluding seedlings of natural origin (Hyppönen and Hallikainen 2011). This was at about the same level as in normal spring and early summer seedings in Finland (Hyppönen 1998; Hallikainen et al. 2004; Rummukainen et al. 2011; Miettinen et al. 2022). Therefore, based on the results of Hyppönen and Hallikainen (2011), one can ask whether direct seeding in late autumn (October and November) could be regarded as a feasible alternative, at least in northern Fennoscandia (Solbraa and Andersen 1997). However, further experimental research was suggested (Hyppönen and Hallikainen 2011) to confirm these inventory results.

Despite the good results of late autumn seeding in Lapland, spring and early summer are still generally considered the best times for direct seeding of Scots pine in northern Finland. However, late autumn has gradually become another potentially successful seeding period in Finnish guidelines and textbooks for northern Finland, in addition to spring and early summer (Nygren 2011; Äijälä et al. 2019; Metsähallitus 2021). On the other hand, late autumn seeding is not recommended in southern Finland due to warm weather. Nevertheless, satisfactory but variable initial autumn seeding results have been observed also in southern Finland (Kaunisto 1974; Kinnunen 1982; Helenius 2016).

Also in Sweden, where conditions are more or less the same as in Finland, spring and early summer (April, May and June) are regarded as the best seeding times for Scots pine (Bergsten and Sahlén 2013; Lundström 2015). Contrary to Finnish recommendations and guidelines, late autumn is still not recommended even in northern Sweden. In Sweden, late autumn seeding is seen as a way of storing seeds in the regeneration area for early germination in spring, and seeds stored in this way are considered to “have a very limited capability to survive on the soil over winter” (Bergsten and Sahlén 2013; Ersson 2021). Consequently, it has been stated that it is not possible to apply conventional autumn seeding of Scots pine without coating the seeds (Pamuk 2004). The purpose of coating is to prevent the seeds from absorbing water above a certain threshold in autumn, which could trigger seed germination and subsequent freezing in the winter. However, coating increases the price of the seed. For lodgepole pine, direct seeding in late autumn is acceptable due to the natural adaptation of its seeds to winter storage (Bergsten and Sahlén 2013; Ersson 2021).

Based on all the above, the aim of this study was to experimentally test the previous results of the inventory-based study on late autumn direct seeding of Scots pine in northern Fennoscandia (Hyppönen and Hallikainen 2011). In addition, the study period was extended from spring to very late autumn and even early winter when the snow fall took place in order to cover the whole range of potential seeding times and to enable a comprehensive comparison of different seeding time alternatives. The aim was also to examine whether lodgepole pine differs from Scots pine in terms of suitable seeding times. Finally, we wanted to study how different site factors affect the regeneration.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Study area and experimental design

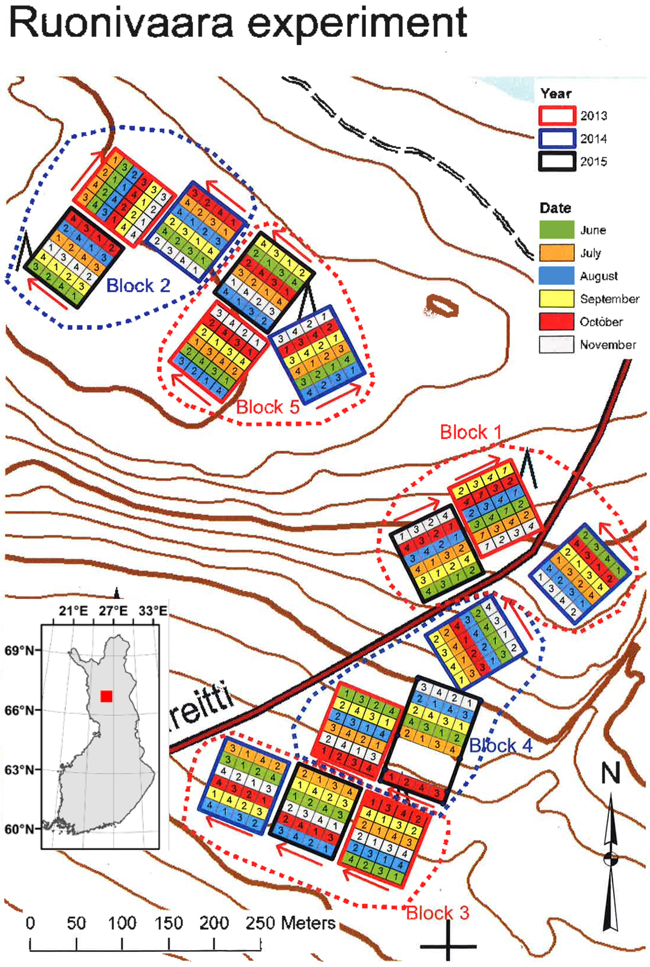

The field experiment is located in Ruonivaara, Sodankylä in Central Finnish Lapland (Fig. 1). The area was selected because it represents a typical northern boreal pine forest environment with rather harsh climate conditions and moraine soils typical for direct seeding of Scots pine. The experimental field was about 5 ha in area, and it was divided into five blocks situated at different altitudes. The blocks were further divided into three squares of about 100 m × 100 m (unless large stones or other obstacles forced to enlarge the area, cf. Fig. 1), for which the annual seeding repetitions (2013, 2014 and 2015) were randomly allocated. These 100 m × 100 m squares are later referred to as annual squares. The main weather parameters for the period of seeding and monitoring (2013–2017) of the nearest meteorological observation station in Sodankylä, about 20 km to the north-west, are presented in Table 1. We want to highlight that the experimental field is around 60–100 meters higher in altitude than the meteorological station, hence the climate is a bit more extreme compared to what is seen in Table 1.

Fig. 1. Location of the experiment and the structure of the experimental design with five blocks divided randomly to annual squares (marked with either black, blue or red borderline) that were further randomly divided into six monthly scarification strips.

| Table 1. Starting date (day/month) of spring, summer, autumn and winter* as well as start and end date of growing season (GS**) in Sodankylä (in Tähtelä, the closest meteorological station of Finnish Meteorological Institute) during 2013–2017. | ||||||

| Year | Spring | Summer | Autumn | Winter | Start of GS | End of GS |

| 2013 | 13/04 | 16/05 | 21/09 | 15/10 | 13/05 | 23/09 |

| 2014 | 11/04 | 29/05 | 13/09 | 10/10 | 19/05 | 20/09 |

| 2015 | 04/04 | 21/06 | 01/09 | 27/10 | 19/05 | 30/09 |

| 2016 | 27/03 | 23/05 | 24/08 | 26/10 | 10/05 | 01/10 |

| 2017 | 29/04 | 07/06 | 23/08 | 19/10 | 09/06 | 07/10 |

| * Definitions: mean daily temperature during spring 0 – +10 °C; summer > +10 °C; autumn +10–0 °C and winter < 0 °C ** The mean daily temperature > +5 °C | ||||||

The annual squares were randomly divided into six strips representing the months of direct seeding from June to November. Each monthly strip was scarified (disc trenching, Figure S1a in Supplementary file S1) just before direct seeding during the first week of each seeding month. These strips are later referred to as scarification strips.

The scarification strips were further divided into four seeding squares (Fig. 1). The four treatments randomly allocated on the seeding squares were: 1) direct seeding with bare Scots pine seeds, 2) Scots pine seeds in seed packs, 3) bare non-stratified lodgepole pine seeds and 4) bare stratified (cold-wet treated) lodgepole pine seeds. Only the results of the bare seed seeding (i.e. treatments 1, 3 and 4) are analysed and reported in this article. Scots pine seeds were collected by Metsähallitus from forests in Sodankylä at an altitude of 300–350 metres. The seeds had a germination rate of 95%, and the weight of one thousand seeds was 4.52 g. Lodgepole pine seeds originated from Galtström (central Sweden), with a germination rate of 96% and a thousand-seed weight of 4.21 g. Stratification of lodgepole pine seeds was performed by cold-wet treatment for 20 days at +5 °C under humid conditions. In each seeding square, ten seeding points were systematically located using an iron micro-preparation grid of 16 depressions (Suppl. file S1: Figures S1b and S1c). Two of the 16 depressions were used in such a way that one seed was systematically placed into the depressions of the lower left and upper right corners (in the direction shown in Fig. 1 and in Suppl. file S1: Figure S1b) of a seeding point (in total two seeds per seeding points, and 20 seeds per seeding square) and lightly covered with mineral soil.

The seeding points were monitored 8–12 times, depending on the month of seeding, for at least two growing seasons after each seeding. The monitoring took place during six years between 2013–2017 (Tables 1 and 2 in Suppl. file S2). Monitoring was carried out on the same calendar dates as the direct seeding, i.e. during the first week of each month (June–October). The first monitoring period of each seeding time was at the same time with the next seeding (e.g. June 2013 seeding was monitored for the first time in July 2013, and July 2013 seeding in August 2013 etc.), except in the case of October. Due to the snow cover, the monitoring was paused after October for the winter and continued in June of the following year. Seeding in November was carried out despite the possible presence of snow. Despite the occurrence of snow cover at some instances, seeding was performed similarly to other seeding months, i.e. on bare exposed mineral soil after disc trenching and not on the snow surface.

Several potential explanatory variables were measured in the vicinity of each seeding point (Table 2). Of these, the thickness of the humus layer was measured in the close vicinity of the seeding point on undisturbed ground vegetation outside of the disc trenching track. The proportion (%) of undisturbed humus (organic soil) layer or vegetation, mixed mineral soil and humus layer, and exposed mineral soil were measured within a 0.5 × 0.5 m grid positioned around a seeding point. The soil type (gravel: grain size 2–20 mm, sand: 0.063–2 mm or silt: 0.002–0.063 mm) was determined by visual inspection from the soil beside the seeding point. The microtopography of the seeding point compared to the surroundings were visually classified as upper, same or lower.

| Table 2. Explanatory variables (measured in the vicinity of seeding points) that have been tested in the models and their distributions. In addition to the variables mentioned in the table, seed type (Scots pine, lodgepole pine and stratified lodgepole pine), seeding month and inventory number were tested as the main important variables in the models. | ||||

| Variable | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Median |

| Continuous variables | ||||

| Thickness of humus layer, cm | 1.00 | 7.00 | 2.47 | 2.00 |

| Stoniness, (depth of an iron stick in the ground) | 0.00 | 52.00 | 9.49 | 7.00 |

| Proportion of untouched humus or vegetation, % | 0.00 | 50.00 | 0.38 | 0.00 |

| Proportion of mixed humus and mineral soil, % | 0.00 | 100.00 | 14.85 | 10.00 |

| Proportion of exposed mineral soil, % | 0.00 | 100.00 | 82.58 | 90.00 |

| Categorical variables | ||||

| Soil type | n | % | ||

| Gravel | 1174 | 34.55 | ||

| Sand | 1926 | 56.68 | ||

| Silt | 298 | 8.77 | ||

| Microtopography (seeding point compared to surroundings) | ||||

| Upper | 1349 | 39.70 | ||

| Same | 1949 | 57.36 | ||

| Lower | 100 | 2.94 | ||

2.2 Data analysis

The response variable was the presence or absence of seedlings in a seeding point. Because two seeds were placed in each seeding point (one in each of two depressions of the micro-preparation grid), the observation in each inventory was either 0, 1 or 2 seedlings. However, the response used in the statistical models (Model 1 and Model 2) was binary, i.e. the absence or presence of at least one seedling.

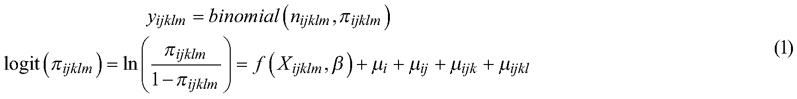

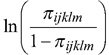

Model 1 was fitted using only the data of the last inventory. Thus, Model 1 is a “final summary” of the survival of the seedlings and is of special importance for practical forestry. Model 2 was constructed using the longitudinal dataset to study the development of germination and seedling survival over time in more detail.

Generalized linear mixed effects models using the binomial distribution assumption were applied to model the presence of at least one seedling at a seeding point and in an inventory. The mixed model was required due to the five-level nested hierarchy in the experiment. The five-level nested hierarchy consisted of, from the lowest to the highest level: 1) seeding point, that was nested within 2) seeding square, nested within 3) scarification strip, nested within 4) annual square, nested within 5) block (Fig. 1). The lowest-level observations, seeding points, were measured once a month from June to October, in total 8 to 12 times, and one should expect that the probabilities to find a seedling in the subsequent measurements were higher than in the measurements having longer time difference. Thus, first-order autoregressive (AR(1)) correlation structure for the error was used in Model 2. The multi-level hierarchy and the AR(1) structure with many fixed factors and covariates made achieving the convergence a bit challenging. Thus, despite the rather large data, only the main effects and most of the two-way interactions in the fixed part of the models could be tested. Furthermore, it should be emphasized that these models are not censored life expectancy models (such as Cox models), but only give the probabilities to observe the presence of a seedling at the observation point at a given time.

The potential explanatory variables, measured in the vicinity of each seeding point, (Table 2) and their two-way interactions were tested as factors or covariates in the models. The most important (key) variables in the models were: 1) seeding month (June–November), 2) seed type (Scots pine, non-stratified lodgepole pine and stratified lodgepole pine) and 3) inventory number that contains the time period between June–October with one-month time interval.

Model 1 can be described as:

where y is the probability of the event, i.e. “a seedling could be found in the seeding point at the last inventory”. Binomial (nijklm, πijklm) denotes the binomial distribution with parameters n describing binomial sample size, in our case the number of all the observations of the seeding points and π describing the proportion, or probability of the occurrences of observed seedlings. is a logit-link function and f(.) describes the linear function with arguments Xijklm (i.e. fixed predictors, could be measured at the levels from i to m) and β (i.e. fixed parameters). Terms μi, μij, μijk and μijkl represents the random, normally distributed effects of block i, annual square j, monthly scarification strip k and seeding square l, respectively. The random effects have a mean of zero and constant variances.

is a logit-link function and f(.) describes the linear function with arguments Xijklm (i.e. fixed predictors, could be measured at the levels from i to m) and β (i.e. fixed parameters). Terms μi, μij, μijk and μijkl represents the random, normally distributed effects of block i, annual square j, monthly scarification strip k and seeding square l, respectively. The random effects have a mean of zero and constant variances.

The structure of the statistical logistic autoregressive mixed model (Model 2 fitted using the longitudinal dataset) can be described as:

where y is the probability of the event, i.e. “a seedling could be found in the seeding point at the inventory t”. Binomial (nijklmt, πijklmt) denotes the binomial distribution with parameters n describing binomial sample size, in our case the number of all the observations of the seeding points and π describing the proportion, or probability of the occurrences of observed seedlings.  is a logit-linkfunction and f(.) describes the linear function with arguments Xijklmt (i.e. fixed predictors, could be measured at the levels from i to t) and β (i.e. fixed parameters, t being the number of inventory). Terms μi, μij, μijk, μijkl and μijklm represents the random, normally distributed effects of block i, annual square j, monthly scarification strip k, seeding square l, and seeding point m, respectively. The lowest level observation in Model 2 is the longitudinal measurement t, we used the series of eight measurements. The subsequent measures (t and t–1) were assumed to be autocorrelated (AR(1)), revealed by the estimated autocorrelation coefficient phi.

is a logit-linkfunction and f(.) describes the linear function with arguments Xijklmt (i.e. fixed predictors, could be measured at the levels from i to t) and β (i.e. fixed parameters, t being the number of inventory). Terms μi, μij, μijk, μijkl and μijklm represents the random, normally distributed effects of block i, annual square j, monthly scarification strip k, seeding square l, and seeding point m, respectively. The lowest level observation in Model 2 is the longitudinal measurement t, we used the series of eight measurements. The subsequent measures (t and t–1) were assumed to be autocorrelated (AR(1)), revealed by the estimated autocorrelation coefficient phi.

In the model construction, we assumed that due to the snowpack and subzero temperatures the wintertime (end of October – late May) is a dormant season for seeds or seedlings, and that the autoregressive structure (lag 1) could hold despite the winter rest (when there were no inventories). The autoregressive structure in the model assumed that the inventory number was treated as a continuous variable (step of one unit), where, for example, for the June seeding, the fourth inventory in October was followed by the fifth inventory in June of the following year, and so on.

Although there were inventories from 1 to 12 available, we ignored the first inventory in the longitudinal analysis (Model 2) because only about half of the seeding points showed germination compared to the second inventory. Furthermore, including the first inventory in the modelling data of Model 2 has a disproportional effect on the model predictions. The inventory number could not be used as a categorical variable due to convergence problems.

The models were computed using R-package MASS (Venables and Ripley 2002) using its function glmmPQL, because it could handle autocorrelated (AR(1)) errors. The function could also estimate needed dispersion parameter for binomial distribution. The predictions for the models were computed and plotted using R-package effects (Fox 2003; Fox and Weisberg 2018). Area under a Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve was computed using R-package pROC (Robin et al. 2011). The ROC-curve (Receiver operating characteristic curve:) is a visual representation of model performance across all thresholds (Nahm 2022). All the statistical computations were made in R statistical environment (R Core Team 2022).

3 Results

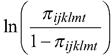

The model for the final inventory (Model 1) showing the probability for at least one living seedling in a seeding point at the end of the monitoring period, clearly showed that there were large differences between seed types in different seeding times. For Scots pine, the best time for seeding was either early summer or late autumn and early winter. The probability for having at least one seedling in a seedling point was 0.65 for November, 0.47 for June, 0.43 for July, 0.41 for October, 0.20 for August, and 0.15 for September (Fig. 2a, Table 3). For both seed types of lodgepole pine, all seeding times showed good success (i.e., probability greater than 0.4). Late autumn and early winter were the most successful seeding times for non-stratified and especially for stratified lodgepole pine (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2. Predictions (with 95% confidence intervals) for the logistic mixed effects model predicting the probability of observing at least one seedling on the seeding point seeded in different months at the time of the last inventory (Model 1, Table 3). Predictions were computed for the interaction of seed type and seeding month (a), thickness of humus layer (b) and proportion of exposed mineral soil (c). Seed type abbreviations are: Scots as Scots pine, Lodgepole as lodgepole pine and Lodgepole strat. as stratified seeds of lodgepole pine.

| Table 3. Parameter estimates and tests of the logistic mixed effects model (Model 1) for the observed seedling on the seeding point in the last inventory. Lodgepole denotes Lodgepole pine and strat. stratified seed. Classification efficiency (ROC) = 68.15 % (marginal model). Interaction effects are separated with : and reference category is expressed as (ref.) | |||||

| Variable / parameter | Estimate | Std.error | df | t- or χ2-value | p |

| Fixed effects | |||||

| Intercept | 5.573E-01 | 3.329E-01 | 2427 | 1.674 | 0.094 |

| Month (ref. June) | - | - | 5 | 69.327 | < 0.001 |

| July | –1.471E-01 | 2.970E-01 | 70 | –0.495 | 0.622 |

| August | –1.267E+00 | 3.194E-01 | 70 | –3.967 | < 0.001 |

| September | –1.583E+00 | 3.285E-01 | 70 | –4.820 | < 0.001 |

| October | –2.373E-01 | 2.951E-01 | 70 | –0.804 | 0.424 |

| November | 7.708E-01 | 2.984E-01 | 70 | 2.583 | 0.012 |

| Seed type (ref. Scots pine) | - | - | 2 | 1.225 | 0.542 |

| Lodgepole | 5.861E-02 | 2.742E-01 | 168 | 0.214 | 0.831 |

| Lodgepole, strat. | 2.873E-01 | 2.752E-01 | 168 | 1.044 | 0.298 |

| Depth of humus layer, cm | 1.079E-01 | 4.925E-02 | 2427 | 2.192 | 0.029 |

| Exposed mineral soil % | –1.153E-02 | 2.554E-03 | 2427 | –4.517 | < 0.001 |

| Month:Seedtype | - | - | 10 | 51.762 | < 0.001 |

| July:Lodgepole | 1.145E-01 | 3.922E-01 | 168 | 0.292 | 0.771 |

| August:Lodgeople | 1.628E+00 | 4.093E-01 | 168 | 3.978 | < 0.001 |

| September:Lodgepole | 1.985E+00 | 4.149E-01 | 168 | 4.785 | < 0.001 |

| October:Lodgepole | 8.961E-01 | 3.920E-01 | 168 | 2.286 | 0.024 |

| November:Lodgepole | –1.267E-01 | 3.947E-01 | 168 | –0.321 | 0.749 |

| July:Lodgepole strat. | 2.141E-01 | 3.928E-01 | 168 | 0.545 | 0.586 |

| August:Lodgepole strat. | 1.096E+00 | 4.089E-01 | 168 | 2.682 | 0.008 |

| September:Lodgepole strat | 1.803E+00 | 4.163E-01 | 168 | 4.332 | < 0.001 |

| October:Lodgepole strat | 9.972E-01 | 3.968E-01 | 168 | 2.513 | 0.013 |

| November:Lodgepole strat | 2.112E-01 | 4.036E-01 | 168 | 0.523 | 0.602 |

| Random effects | |||||

| Block (level 1) | 2.863E-03 | ||||

| Annual square (level 2) | 0.060 | ||||

| Scarification strip (level 3) | 0.081 | ||||

| Seeding square (level 4) | 0.163 | ||||

| Dispersion parameter | 0.945 | ||||

The thickness of the adjacent humus layer, measured under undisturbed ground vegetation as close as possible to the seeding point, slightly affected the success of seeding. The thicker the humus layer, the better the result. On the other hand, an increasing proportion of exposed mineral soil slightly decreased the success (Fig. 2b and c, Table 3).

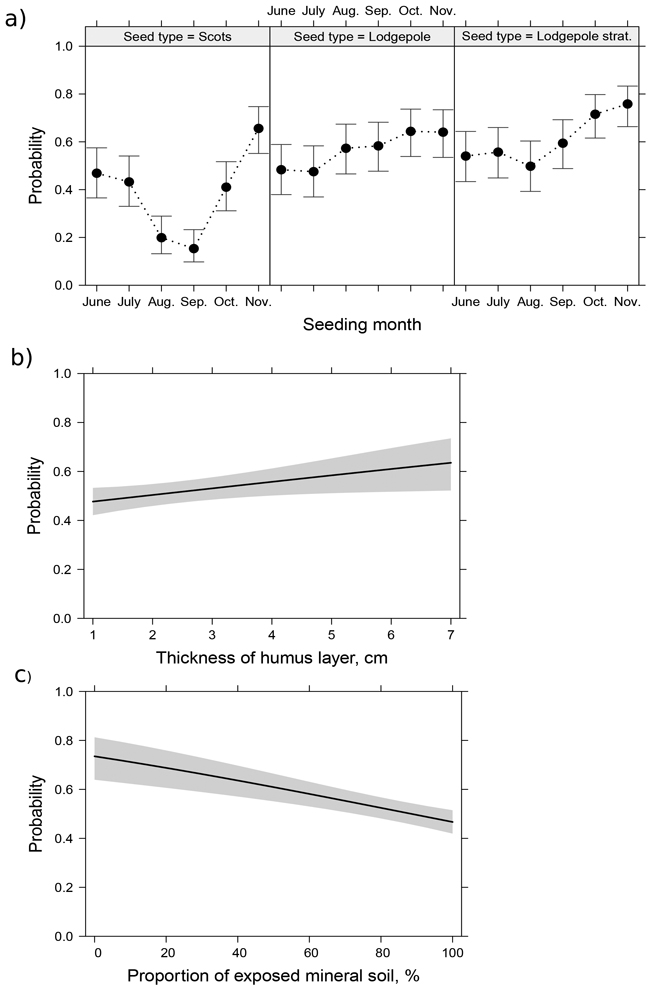

Model 2 was constructed to inspect the processes of seed germination and seedling survival over time more closely. The results of Model 2 confirmed the results of Model 1. For Scots pine, Model 2 also showed that the best seeding times were early summer and late autumn as well as early winter, while the poorest seeding times were late summer and early autumn. For both seed types of lodgepole pine, timing was not so critical (Fig. 3a, Table 4). The results of Model 2 also revealed that the success of seeding in September improved slightly over time, while the success in other seeding times tended to decrease or, at best, remain at the same level (Fig. 3b). In addition, Model 2 revealed that the seeding success of Scots pine was clearly decreasing over time, while the trend of stratified lodgepole pine was slightly decreasing and that of non-stratified lodgepole pine was even increasing (Fig. 3c). When the effect of the time was averaged, Model 2 suggested that Scots pine had a higher average level of success than lodgepole pine.

Fig. 3. Predictions (with 95% confidence intervals) for the logistic mixed effects model predicting the probability of observing a seedling on the seeding point in different inventories (Model 2, Table 4). Predictions were computed for the interaction of seeding month and seed type (a), the interaction of the number of inventory (time series) and seeding month (b), the interaction of the number of inventory and seed type (c), the interaction of the number of inventory and the soil type of seeding point (d) and the interaction of the number of inventory and the proportion of exposed mineral soil (e). Seed type abbreviations: see Fig. 2.

| Table 4. Parameter estimates and tests of the logistic mixed effects model (Model 2) with autoregressive (AR(1)) error term for the probability of at least one seedling on the seeding point at the certain point and time of inventory. Lodgepole denotes Lodgepole pine and strat. stratified seed. Classification efficiency (ROC) = 70.25 % (marginal model). Interaction effects are separated with : and reference category is expressed as (ref.). | |||||

| Variable / parameter | Estimate | Std.error | df | t- or χ2-value | p |

| Fixed effects | |||||

| Intercept | 1.910E+00 | 3.524E-01 | 19641 | 5.421 | 0.000 |

| Month (ref. June) | - | - | 5 | 307.592 | < 0.001 |

| July | –1.701E-01 | 2.938E-01 | 70 | –0.579 | 0.564 |

| August | –2.283E+00 | 2.883E-01 | 70 | –7.919 | 0.000 |

| September | –4.274E+00 | 3.238E-01 | 70 | –13.200 | 0.000 |

| October | –6.333E-01 | 3.004E-01 | 70 | –2.108 | 0.039 |

| November | 8.189E-01 | 3.339E-01 | 70 | 2.453 | 0.017 |

| Seed type (ref. Scots pine) | - | - | 2 | 72.124 | < 0.001 |

| Lodgepole | –2.102E+00 | 2.525E-01 | 168 | –8.326 | 0.000 |

| Lodgepole, strat. | –8.372E-01 | 2.603E-01 | 168 | –3.216 | 0.002 |

| Soil type (ref. Gravel) | - | - | 2 | 18.364 | < 0.001 |

| Sand | –4.712E-02 | 1.240E-01 | 2426 | –0.380 | 0.704 |

| Silt | 9.441E-01 | 2.405E-01 | 2426 | 3.926 | 0.000 |

| Inventory | –4.079E-02 | 3.553E-02 | 19641 | –1.148 | 0.251 |

| Exposed mineral soil % | 2.985E-03 | 3.142E-03 | 19641 | 0.950 | 0.342 |

| Month:Seedtype | - | - | 10 | 118.994 | < 0.001 |

| July:Lodgepole | 9.186E-02 | 3.092E-01 | 168 | 0.297 | 0.767 |

| August:Lodgeople | 1.195E+00 | 3.134E-01 | 168 | 3.814 | 0.000 |

| September:Lodgepole | 3.072E+00 | 3.429E-01 | 168 | 8.959 | 0.000 |

| October:Lodgepole | 1.883E+00 | 3.256E-01 | 168 | 5.782 | 0.000 |

| November:Lodgepole | 8.297E-01 | 3.364E-01 | 168 | 2.466 | 0.015 |

| July:Lodgepole strat. | 2.940E-02 | 3.151E-01 | 168 | 0.093 | 0.926 |

| August:Lodgepole strat. | 6.514E-01 | 3.161E-01 | 168 | 2.061 | 0.041 |

| September:Lodgepole strat | 2.297E+00 | 3.454E-01 | 168 | 6.650 | 0.000 |

| October:Lodgepole strat | 1.414E+00 | 3.350E-01 | 168 | 4.221 | 0.000 |

| November:Lodgepole strat | 5.755E-01 | 3.494E-01 | 168 | 1.647 | 0.102 |

| Month:Inventory | - | - | 5 | 224.052 | < 0.001 |

| July:Inventory | –2.612E-03 | 1.947E-02 | 19641 | –0.134 | 0.893 |

| August:Inventory | 1.219E-01 | 2.027E-02 | 19641 | 6.015 | 0.000 |

| September:Inventory | 2.393E-01 | 2.289E-02 | 19641 | 10.452 | 0.000 |

| October:Inventory | –6.174E-02 | 2.457E-02 | 19641 | –2.513 | 0.012 |

| November:Inventory | –1.084E-01 | 2.763E-02 | 19641 | –3.923 | 0.000 |

| Seedtype:Inventory | - | - | 2 | 140.230 | < 0.001 |

| Lodgepole:Inventory | 1.976E-01 | 1.670E-02 | 19641 | 11.827 | 0.000 |

| Lodgepole_strat:Inventory | 1.171E-01 | 1.711E-02 | 19641 | 6.845 | 0.000 |

| Soiltype:Inventory | - | - | 2 | 39.274 | < 0.001 |

| Sand:Inventory | –8.518E-03 | 1.474E-02 | 19641 | –0.578 | 0.563 |

| Silt:Inventory | –1.819E-01 | 2.975E-02 | 19641 | –6.113 | 0.000 |

| Inventory:Exposed mineral soil, % | –1.819E-03 | 3.751E-04 | 19641 | –4.850 | 0.000 |

| Random effects, AR(1) | |||||

| Block (level 1) | 4.345E-18 | ||||

| Annual square (level 2) | 0.052 | ||||

| Scarification strip (level 3) | 0.089 | ||||

| Seeding square (level 4) | 0.105 | ||||

| Seeding point (level 5) | 1.962E-06 | ||||

| Dispersion parameter | 0.993 | ||||

| Phi | 0.831 | ||||

When the other explanatory variables, except inventory number and soil type, were averaged to their mean values, the predictions of Model 2 suggested that the seeds sown on silty soils had the greatest decline in success in the course of time compared to those sown on gravel or sand, although the success in the early inventories (2nd or 3rd inventory) was highest on silt (Fig. 3d, Table 4).

The presence of seedlings also differed depending on the proportion of exposed mineral soil or, conversely, the humus coverage (undisturbed, disturbed or mixed with the mineral soil). Success decreased slightly as the proportion of exposed mineral soil increased when the seed types were averaged (Fig. 3e, Table 4).

4 Discussion

Our results clearly show that direct seeding of Scots pine was most successful in early summer as well late autumn and early winter, i.e., during a period when germination did not start, and actual winter conditions are expected to subsequently maintain the seeds at low moisture content. The predicted probability of emergence and survival for Scots pine at the end of the monitoring period varied greatly between the inventory months: from a minimum in September (15% for survival of at least one seedling out of two after two growing seasons) to a maximum in November (65%). Based on this study, the best time for direct seeding in the northern parts of Fennoscandia is the early days of November (i.e. early winter), followed by June, July and October. Solely on the basis of long-term weather data (https://www.ilmatieteenlaitos.fi/), all of those months listed, except July, would be a suitable time for direct seeding. Late July is often too hot and dry for the newly germinated seedlings to survive. We did not, however, measure weather data in situ, so we cannot definitively conclude that conditions were hot and dry, nor can we rule out other factors that might suggest avoiding direct seeding in late July.

One of the aims of this study was to experimentally test the earlier results of the inventory-based study on direct seeding of Scots pine in late autumn (Hyppönen and Hallikainen 2011). The earlier study was based on the inventory of practical seedling stands established by direct seeding in connection with disc trenching and using 350 g of Scots pine seeds ha–1, when the seeds were spread on site preparation track as targeted broadcast seeding. Instead, the present experimental study was established manually on a fresh disc trencher track, using two seeds per seeding point, and the results were expressed as seedling emergence and survival probabilities. In addition to disc trenching, we used the micro-preparation grid not used in practical seeding. In this study, the use of the micro-preparation grid allowed us to create uniform seeding points and help identify them in the subsequent inventories. In practical forestry machine seeding carried out in combination with soil preparation most likely results in larger variation in seeding success compared to the standardized method used in this study (see also Winsa and Bergsten 1994). We, however, aimed for as little as possible unwanted variation in results, hence we used the method of micro-preparation grid described above.

The dissimilarity of the studies and the presentation of the results makes it difficult to accurately compare the results (Kinnunen 2003; Nygren 2011). On the other hand, we know that when comparing manual and mechanical direct seeding, the results can be quite similar on average (Kinnunen 2003). We also know that mechanical direct seeding is a biologically and technically feasible method that is generally used in Finland (Hyppönen 1998; Kinnunen 2003; Rummukainen et al. 2011; Hallongren et al. 2012).

The earlier inventory-based study (Hyppönen and Hallikainen 2011) and the present experimental study differ regionally, temporally and in the methodology of data collection. The fact that the studies are so different from each other and yet agree in their results points out the applicability of late autumn as an appropriate direct seeding period for Scots pine. Hence, the present study confirms the results of the inventory-based study and also supports the results of some older studies (Hedemann-Gade 1927; Wibeck 1927; Kangas 1940; Kinnunen 1982; Solbraa and Andersen 1997). Nevertheless, it is possible that climate change may influence this conclusion in the future and bring along risks for direct seeding in late autumn. However, as our results pointed out that as long as the snow situation or freezing of the ground enables direct seeding one can postpone direct seeding as far towards the winter as possible. It appears that as long as we delay direct seeding to a point where the seeds do not absorb water – which could trigger germination and subsequent freezing during the winter – there is no restriction on how late in autumn or winter direct seeding can be used.

According to Finnish guidelines, direct seeding of Scots pine in late autumn is nowadays recommended for northern Finland, but not for southern Finland (Nygren 2011; Äijälä et al. 2019; Metsähallitus 2021). Nevertheless, some positive but variable results have also been obtained in southern Finland in peatlands (Kaunisto 1974) and mineral soils (Kinnunen 1982; Helenius 2016). In the experiment in Suonenjoki in central Finland, the results depended strongly on how well the seeds became covered in seeding (Helenius 2016; see also Nilson and Hjältén 2003 about the risk of predation). Success was 2–3 times better when the seeds were covered than when they were not. According to earlier research, there are no major problems with mechanical direct seeding in terms of coverage (Hyppönen 1998; Kinnunen 2003; but see Nygren et al. 2013). Though, in modern practical forestry most of the sown seeds are covered also in machine seeding.

In addition to early summer, late autumn and early winter, early July proved to be a successful time for seeding Scots pine. It seems that, with certain reservations (Hedemann-Gade 1927; Pohtila 1977; Nygren 2011), the direct seeding period of spring and early summer can be extended into early July in northern Finland, if the weather is not forecasted to be too hot and dry. In fact, in the current guidelines of Metsähallitus (2021), the seeding period of spring and early summer already extends from snowmelt to early July in northern Finland. In the guidelines for southern Finland, the corresponding period does not extend further than the summer solstice. In the present experiment we have not studied seeding in mid and late July. According to earlier studies, this period is not favourable and cannot be recommended (Heikinheimo 1940; Kangas 1940; Kinnunen 1992; de Chantal et al. 2003; Nygren 2011).

The most unsuccessful times for direct seeding of Scots pine were, as expected, late summer and early autumn (August and particularly September), which is well in line with many Finnish and Swedish studies and current forest management guidelines (e.g. de Chantal et al. 2003; Nygren 2011; Bergsten and Sahlén 2013; Äijälä et al. 2019; Ersson 2021; Metsähallitus 2021). It seems that in August, germinants and seedlings did not reach sufficient size, root development and hardiness for winter conditions and suffered from frost, frost heaving, ice and snow pressure and other winter damage, which are the most crucial factors affecting the destruction of germinants and seedlings. Especially, if sown in September, it is likely that the seeds did not have time to germinate, and those that did germinate were repeatedly frozen and thawed, eventually destroying their structure (Pamuk et al. 2003). On the other hand, monitoring the germination in the course of time revealed that Scots pine seeded in September were germinating still about two years after seeding (8th inventory, data not shown). Hence, September gradually more or less reached August in regeneration success. However, postponing the seeding to October or November prevented both freezing and thawing of the seeds and postponed germination until the following summer (Kinnunen 1982; Winsa and Bergsten 1994; Wennström et al. 1999, 2007; Bergsten et al. 2001; Hyppönen and Hallikainen 2011).

The current guidelines of Swedish Forest Agency recommend direct seeding of lodgepole pine in autumn because its seeds are naturally adapted to overwinter well in the soil (Bergsten and Sahlén 2008, 2013; Ersson 2021; see also Solbraa and Andersen 1997; Varmola 2000). The present study supports the Swedish guidelines, as direct seeding in late autumn produced the best monthly seedling establishment probabilities for both non-stratified and particularly for stratified lodgepole pine. On the other hand, all other seeding months were good enough for sufficient seedling establishment, so that both stratified and unstratified lodgepole pine can be seeded from spring through until early winter.

In the comparison between Scots pine and lodgepole pines, the final results at the end of the monitoring period were similar for the June, July and November seedings (Solbraa and Andersen 1997; Varmola et al. 2000). The greatest differences between seed types were found in the August and September seedings. During these months the probability of success was much higher for both seed types of lodgepole pine than for Scots pine. In addition, there was a greater difference between the survival probabilities of October and November for Scots pine, whereas there was no notable difference between these months for lodgepole pine.

It is well known that site preparation is a key to successful seedling establishment in both natural and artificial regeneration in Scots pine stands. With increasing proportion of exposed soil surface, the number of seedlings or the probability of success usually increases (Lehto 1969; Hallikainen et al. 2004; Hyppönen et al. 2005; Hyppönen and Hallikainen 2011; Rautio et al. 2023). In general, however, light site preparation is enough to guarantee successful seedling establishment in the regeneration of Scots pine forests (Hallikainen et al. 2019; Miettinen et al. 2022; Miettinen et al. 2024).

On the contrary to exposed mineral soil, thickness of a humus layer is usually negatively correlated with regeneration success with Scots pine. The thicker the humus layer, the poorer is the regeneration result in both natural and artificial regeneration (Hyppönen 1998; Hyppönen 2002; Hallikainen et al. 2004; Hyppönen and Hallikainen 2011; Rautio et al. 2023). Site preparation mitigates this problem (Kuuluvainen and Pukkala 1989; Hallikainen et al. 2004; Rautio et al. 2023; Miettinen et al. 2024). Contrary to earlier research, in this study an increasing proportion of exposed mineral soil in the vicinity of seedlings of all seed types decreased the average success probability in the last monitoring after at least two growing seasons after seeding. Furthermore, the thickness of humus layer slightly increased the probability of success, also contrary to earlier research. As the thickness of humus layer was measured outside the track of a disc trencher, it doesn’t directly indicate the quality of the seeding point. A probable cause for these results is that in site preparation more humus is mixed with mineral soil in soils with a thick humus layer. Mixture of organic and mineral soil might reduce e.g. frost heaving and other negative effects that seeding on deeper soil horizons might bring along (Winsa 1995; de Chantal et al. 2007, 2008). Frost upheaval was also observed in several places during this experiment (Figure 1d in Supplementary file S1). A thicker humus layer can also indicate moister micro-locations in the underlying mineral soil, which in turn can increase the success of seed germination. The humus layer may also help preserve water in the mineral soil, as hydraulic conductivity is high under rainy conditions.

Because all seeds were sown in the track of a disc trencher, the above results suggest that it would be better for Scots pine if a seeding point was a mixture of humus layer and mineral soil (Hertz 1934; Winsa 1995; Miettinen et al. 2024). On coarse-grained soils, mixing humus with the mineral soil can increase the soil water holding capacity. On fine-grained soils, mixing humus with mineral soil can increase porosity, leading to increased soil aeration (Bergsten et al. 2003). In both coarse-grained and fine-grained soils, direct seeding (seed germination and the survival of germinants/seedlings) can thus be improved by mixing the humus layer with the underlying mineral soil. A large area of bare mineral soil is associated with temperature and moisture fluctuations (including frost) and frequent droughts, creating an extreme and challenging environment that causes high mortality of small seedlings (Pohtila 1977; Wennström et al. 2007; Kyrö et al 2021). This may explain why we found a decrease in the success probability with increasing proportions of exposed mineral soil in the vicinity of seedlings.

In conclusion our results clearly show that the best time for direct seeding in the northern parts of Fennoscandia is either early summer or late autumn and early winter. Then again, the lowest survival probabilities in September (15%) and in August (20%) are in fact not that poor if one is prepared to tolerate the extra costs of seeds in direct seeding to compensate the loss. This kind of adaptable amount of seed material depending on the seeding month would extend the suitable seeding time continuously from the early summer to the early winter.

Declaration on the availability of research materials

Research data (and metadata) and the R-code of statistical models are available on request from the corresponding author.

Authors’ contributions

M. Hyppönen (MH), V. Hallikainen (VH), P. Rautio (PR), U. Bergsten (UB) and H. Winsa (HW) formulated the research questions. VH, PR and MH designed the experiment. E. Jaskari (EJ) coordinated the fieldwork for the experiment and data management. MH, VH, HW, EJ and PR participated in the fieldwork. VH conducted the statistical analyses and interpretations in cooperation with PR, MH, J. Miina (JM) and S. Valkonen (SV). MH and VH wrote the first draft of the article that PR, JM, SV, P. Helenius, UB, HW and EJ complemented, corrected, and commented. All authors approved the final version of the article.

Acknowledgements

Pekka Närhi, Tarmo Aalto, Eero Siivola, Jukka Lahti, Antti Hannukkala and Pasi Aatsinki among others in Finnish Forest Research Institute (Metla) and Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke) helped to carry out the field measurements and data management. Liisa Hallikainen helped to edit the list of references.

Funding of the research

This study was carried out as a part of the projects Forward (Forest renewal by natural methods) and Transform (Tools for natural regeneration in sustainable forest management) funded by Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke), and as a part of the project NorFor (Solving problems in forest regeneration in northern Fennoscandia) funded by Finnish Forest Research Institute (Metla), Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU), Metsähallitus and Sveaskog.

References

Äijälä O, Koistinen A, Sved J, Vanhatalo K, Väisänen P (eds) (2019) Metsänhoidon suositukset. [Forest management guidelines]. Tapion julkaisuja. https://tapio.fi/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Metsanhoidon_suositukset_Tapio_2019.pdf. Accessed 13 August 2025.

Beckman E, Nilsson A (2014) Evaluation of seeding of lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta Dougl. var. latifolia Engelm.) in the province of Härjedalen. Examensarbete i skogs- och träteknik, Linnéuniversitetet. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:722241/FULLTEXT01.pdf. Accessed 13 August 2025.

Bergsten U, Sahlén K (2008) Sådd. [Direct seeding]. Skogsstyrelsen, Skogsskötselserien 5. https://res.slu.se/id/publ/124466.

Bergsten U, Sahlén K (2013) Sådd. [Direct seeding]. Skogsstyrelsen, Skogsskötselserien 5. https://www.skogsstyrelsen.se/globalassets/mer-om-skog/skogsskotselserien/skogsskotsel-serien-5-sadd.pdf. Accessed 13 August 2025.

Bergsten U, Goulet F, Lundmark T, Löfvenius MO (2001) Frost heaving in a boreal soil in relation to soil scarification and snow cover. Can J Forest Res 31: 1084–1092. https://doi.org/10.1139/x01-042.

Bergsten U, Sahlén K, Charlesworth E, Fredriksson M, Wilhelmsson O (2003) Forest regeneration of pine and spruce from seeds. Handbook. Vindelns Försöksparker, Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet (SLU), Skog & Trä 2/2003.

de Chantal M, Leinonen K, Ilvesniemi H, Westman CJ (2003) Combined effects of site preparation, soil properties, and sowing date on the establishment of Pinus sylvestris and Picea abies from seeds. Can J Forest Res 33: 931–945. https://doi.org/10.1139/x03-011.

de Chantal M, Holt Hansen K, Granhus A, Bergsten U, Ottosson Löfvenius M, Grip H (2007) Frost-heaving damage to one-year-old Picea abies seedlings increases with soil horizon depth and canopy gap size. Can J Forest Res 37: 1236–1243. https://doi.org/10.1139/X07-007.

de Chantal M, Bergsten U, Grip H, Ottosson Löfvenius M (2009) Frost heaving of Picea abies seedlings as influenced by soil preparation, planting technique, and location along gap-shelterwood gradients. Silva Fenn 43: 39–50. https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.214.

Ersson BT (2021) Mechanized direct seeding: good practice examples in optimization of forest operations. Net4Forest. https://res.slu.se/id/publ/112487.

Fox J (2003) Effect displays in R for generalized linear models. J Stat Softw 8: 1–17. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v008.i15.

Fox J, Weisberg S (2018) Visualizing fit and lack of fit in complex regression models with predictor effect plots and partial residuals. J Stat Softw 87: 1–27. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v087.i09.

Häggman J (1987) Voiko männynsiemen jälki-itää? [Can Scots pine seed post-germinate?]. In: Saarenmaa H, Poikajärvi H (eds) Korkeiden maiden metsien uudistaminen. Ajankohtaista tutkimuksesta. Metsäntutkimuspäivät Rovaniemellä 1987. Finnish Forest Research Institute. Research Paper 278: 115–122. https://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:951-40-0832-4.

Hallikainen V, Hyppönen M, Jalkanen R, Mäkitalo K (2004) Metsänviljelyn onnistuminen Lapin yksityismetsissä vuosina 1984–1995. [Success of artificial regeneration in non-industrial private forests in Finnish Lapland in 1984–1995]. Metsätieteen aikakauskirja 1/2004: 3–20. https://doi.org/10.14214/ma.6078.

Hallikainen V, Hökkä H, Hyppönen M, Rautio P, Valkonen S (2019) Natural regeneration after gap cutting in Scots pine stands in northern Finland. Scand J Forest Res 34: 115–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/02827581.2018.1557248.

Hallongren H, Laine T, Juntunen M-L (2012) Metsänhoitotöiden koneellistamisesta ratkaisu metsuripulaan? [Mechanisation of silviculture – solution for the shortage of forest workers?]. Metsätieteen aikakauskirja 2/2012: 95–99. https://doi.org/10.14214/ma.6459.

Hannerz M, Almqvist C, Hörnfeldt R (2002) Timing of seed dispersal in Pinus sylvestris stands in central Sweden. Silva Fenn 36: 757–765. https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.518.

Hedemann-Gade E (1927) Investigations regarding the most suitable time for sowing coniferous seed. Svenska Skogsvårdsföreningens Tidskrift 25: 5–50.

Heikinheimo O (1937) Metsäpuiden siementämiskyvystä II. [About seeding capacity of forest trees]. Commun Inst For Fenn 24.4: 1–67. https://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi-metla-201207171056.

Heikinheimo O (1940) Metsäpuiden taimien kasvatus taimitarhassa. [Growing of tree seedlings in a nursery]. Comm Inst For Fenn 29.1: 1–97. https://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi-metla-201207171061.

Helenius P (2016) Vapusta juhannukseen – onko männyn kylvöaika kiveen hakattu? [From the first of May to Midsummer – is the direct seeding time of Scots pine set in stone?]. Taimiuutiset 3: 6–9. https://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi-fe2016101125040.

Hertz M (1934) Tutkimuksia kasvualustan merkityksestä männyn uudistumiselle Etelä-Suomen kangasmailla. [Studies on the significance of seedbed for the regeneration of Scots pine in the mineral soil forests in Southern Finland.] Comm Inst For Fenn 20.2: 1–98. https://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi-metla-201207171052.

Hokajärvi T (ed) (1997) Metsänhoito-ohjeet. [Forest management guidelines]. Metsähallituksen metsätalouden julkaisuja 10.

Hyppönen M (1998) Koneellisen männynkylvön onnistuminen Länsi-Lapissa. [Success of mechanical direct seeding of Scots pine in Western Lapland]. Metsätieteen aikakauskirja 1/1998: 65–74. https://doi.org/10.14214/ma.6715.

Hyppönen M (2000) Artificial regeneration techniques in Finland. In: Mälkönen E, Babich NA, Krutov VI, Markova IA (eds) Forest regeneration in the northern parts of Europe. Proceedings of the Finnish-Russian Forest Regeneration Seminar in Vuokatti, Finland, Sept. 28th–Oct. 2nd, 1998. Finnish Forest Research Institute, Research Paper 790: 159–167. https://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:951-40-1757-9.

Hyppönen M (2002) Natural regeneration of Scots pine using the seed tree method in Finnish Lapland. Finnish Forest Research Institute, Research Paper 844. https://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:951-40-1824-9.

Hyppönen M, Hallikainen V (2011) Factors affecting the success of autumn direct seeding of Pinus sylvestris L. in Finnish Lapland. Scand J Forest Res 26: 515–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/02827581.2011.586952.

Hyppönen M, Karvonen L (2005) Kylvö. [Direct seeding]. In: Hyppönen M, Hallikainen V, Jalkanen R (eds) Metsätaloutta kairoilla : metsänuudistaminen Pohjois-Suomessa. [Forest regeneration in Northern Finland]. Metsäkustannus Oy, pp 74–81. ISBN 952-5118-66-5.

Hyppönen M, Alenius V, Valkonen S (2005) Models for the establishment and height development of naturally regenerated Pinus sylvestris in Finnish Lapland. Scand J Forest Res 20: 347–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/02827580510036391.

Kangas E (1940) Tuloksia Pohjankankaan ja Hämeenkankaan metsänviljelyksistä. [Results from the forest regeneration in Pohjankangas and Hämeenkangas]. Acta For Fenn 49.4: 1–64. https://doi.org/10.14214/aff.7351.

Kaunisto S (1974) Date of direct seeding on drained peatlands. Folia For 203. https://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:951-40-0112-5.

Keskimölö A, Heikkinen E, Keränen K (eds) (2007) Pohjois-Suomen metsänhoitosuositukset 2007. [Forest management recommendations for Northern Finland]. Metsäkeskus Lappi, Pohjois-Pohjanmaa ja Kainuu. ISBN 9789519873121.

Kinnunen K (1982) Scots pine sowing on barren mineral soils in western Finland. Folia For 531. https://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:951-40-0585-6.

Kinnunen K (1992) Effect of substratum, date and method on the post-sowing survival of Scots pine. Folia For 785. https://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:951-40-1194-5.

Kinnunen K (1996) Kevät- ja syyskylvön onnistuminen eri puulajeilla. [Success of direct seeding of various tree species in spring and in autumn]. In: Laiho O, Luoto T (eds) Metsäntutkimuspäivä Porissa 1995. Finnish Forest Research Institute, Research Paper 593: 4–9. https://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:951-40-1502-9.

Kinnunen K (2003) Konekylvön käyttökelpoisuus männyn uudistamisessa. [Usability of mechanical direct seeding in the regeneration of Pinus sylvestris]. Metsätieteen aikakauskirja 1/2003: 69–72. https://doi.org/10.14214/ma.6675.

Kulju I, Niinistö T, Peltola A, Räty M, Sauvula-Seppälä T, Torvelainen J, Uotila E, Vaahtera E (2023) Metsätilastollinen vuosikirja 2022. [Finnish Statistical Yearbook of Forestry 2022]. Natural Resources Institute Finland, Helsinki. https://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-380-584-2.

Kuuluvainen T, Pukkala T (1989) Effect of Scots pine seed trees on the density of ground vegetation and tree seedlings. Silva Fenn 23: 159–167. https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.a15536.

Kyrö MJ, Hallikainen V, Valkonen S, Hyppönen M, Puttonen P, Bergsten U, Winsa H, Rautio P (2022) Effects of overstory tree density, site preparation and ground vegetation on natural Scots pine seedling emergence and survival in northern boreal pine forests. Can J Forest Res 52: 860–869. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjfr-2021-0101.

Lassila I (1920) Tutkimuksia mäntymetsien synnystä ja kehityksestä pohjoisen napapiirin pohjoispuolella. [Investigations of regeneration and development of Pinus sylvestris at the northern side of the Arctic Circle]. Acta For Fenn 14.3: 1–98. https://doi.org/10.14214/aff.7036.

Lehto J (1969) Studies conducted in northern Finland on the regeneration of Scots pine by means of the seed tree and shelterwood methods. Comm Inst For Fenn 67.4: 1–140. https://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi-metla-201207171099.

Lundström P (2015) Potential for increased area of direct seeding within Holmen Skog. [Potential for increased area of direct seeding within Holmen Skog ]. Institutionen för skogens biomaterial och teknologi, Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet, Arbetsrapport 5/2015. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:slu:epsilon-s-4288.

Metsähallitus (2021) Metsänhoito-ohje. [Guide for silviculture].

Miettinen J, Hallikainen V, Hyppönen M, Bergsten U, Winsa H, Välikangas P, Hiltunen A, Aatsinki P, Rautio P (2022) Effect of site preparation and reindeer grazing on the early-stage success of Scots pine regeneration from seeds in northern Finland and Sweden. Scand J Forest Res 37: 338–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/02827581.2022.2136404.

Miettinen J, Hallikainen V, Valkonen S, Hökkä H, Hyppönen M, Rautio P (2024) Natural regeneration and early development of Scots pine seedlings after gap cutting in northern Finland. Scand J Forest Res 39: 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/02827581.2024.2303022.

Miina J, Saksa T (2008) Predicting establishment of tree seedlings for evaluating methods of regeneration for Pinus sylvestris. Scand J Forest Res 23: 12–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/02827580701779595.

Nahm FS (2022) Receiver operating characteristic curve: overview and practical use for clinicians. Korean J Anesthesiol 75: 25–36. https://doi.org/10.4097/kja.21209.

Nilson E, Hjältén J (2003) Covering pine-seeds immediately after seeding: effects on seedling emergence and on mortality through seed-predation. For Ecol Manag 176: 449–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1127(02)00308-0.

Nygren M (2011) Metsänkylvöopas. Kylvön biologiaa ja tekniikkaa. [The guide for direct seeding. Biology and technics of direct seeding]. Finnish Forest Research Institute. https://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-40-2328-6.

Nygren M, Ikonen N, Helenius P (2013) Siementen itäminen ja taimien orastuminen männyn äeskylvössä – tapaustutkimus. [Germination of seeds and budding of seedlings in mechanical direct seeding – case study]. Metsätieteen aikakauskirja 2/2013: 127–140. https://doi.org/10.14214/ma.6881.

Pamuk G (2004) Controlling water dynamics in Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) seeds before and during seedling emergence. Acta Univ Agric Sueciae. Silvestria 305. https://res.slu.se/id/publ/12015.

Pamuk GS, Bergsten U, Lingois P (2003) Freezing response in Scots pine seeds as assessed by DSC and germination test. Seed Technol 25: 92–103. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23433263.

Pohtila E (1977) Reforestation of ploughed sites in Finnish Lapland. Comm Inst For Fenn 91.4: 1–100. https://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi-metla-201207171124.

Pohtila E, Pohjola T (1985) Soil preparation in reforestation of Scots pine in Lapland. Silva Fenn 19: 245–270. https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.a15422.

R Core Team (2022) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed 13 August 2025.

Rautio P, Hallikainen V, Valkonen S, Karjalainen J, Puttonen P, Bergsten U, Winsa H, Hyppönen M (2023) Manipulating overstory density and mineral soil exposure for optimal natural regeneration of Scots pine. For Ecol Manag 539, article id 120996. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2023.120996.

Renvall A (1912) Die periodischen Erscheinungen der Produktion der Kiefer an der polaren Waldgrenze. [Periodical variation of the production of Scots pine at the Arctic Circle]. Acta For Fenn 1.2: 1–154. https://doi.org/10.14214/aff.7527.

Robin X, Turck N, Hainard A, Tiberti N, Lisacek F, Sanchez J, Müller M (2011) pROC: an open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinform 12, article id 77. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-12-77.

Rummukainen A, Tervo L, Kautto K, Pulkkinen M (2011) Maanmuokkaus- ja kylvölaiteyhdistelmien vertailuja männyn kylvössä Kainuussa ja Pohjois-Pohjanmaalla. [Comparison of site preparation and seeding equipment assemblies in sowing of Scots pine in Kainuu and Northern Ostrobothnia]. Metsätieteen aikakauskirja 1/2011: 13–33. https://doi.org/10.14214/ma.5928.

Sirén G (1952) Observations on stands of Scots pine sown in state forests in Peräpohjola in northern Finland in 1948–1950. Silva Fenn 78: 1–40. https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.a9100.

Solbraa K, Andersen R (1997) Experiments with sowing methods, sowing periods, seed qualities, and different conifer species after ground scarification. Norwegian Forest Research Institute, Report 2. ISBN 8271698141.

Tillman-Sutela E (1995) Structural and seasonal aspects on the imbibition and germination of northern conifer seeds. Acta Univ Ouluensis A 266. ISBN 951-42-4044-8.

Varmola M, Salminen H, Rikala R, Kerkelä M (2000) Survival and early development of Lodgepole pine. Scand J Forest Res 15: 410–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/028275800750172619.

Venables W, Ripley B (2002) Modern applied statistics with S, 4th edition. Springer, New York (NY). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-21706-2.

Wennström U, Bergsten U, Nilsson J-E (1999) Mechanized microsite preparation and direct seeding of Pinus sylvestris in boreal forests – a way to create desired spacing at low costs. New Forests 18: 179–198. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006506431344.

Wennström U, Bergsten U, Nilsson J-E (2007) Seedling establishment and growth after direct seeding with Pinus sylvestris: effects of seed type, seed origin, and seeding year. Silva Fenn 41(2): 299–314. https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.298.

Wibeck E (1927) Spring or autumn sowing. Meddelanden från Statens Skogsförsöksanstalt 23.4: 217–294. https://res.slu.se/id/publ/124778.

Wikström K (1922) Höstsådd eller vårsådd av tall? [Autumn or spring sowing of Scots pine?]. Skogsvårdsföreningens Tidskrift 20: 144–160.

Winsa H (1995) Effects of seed properties and environment on seedling emergence and early establishment of Pinus sylvestris L. after direct seeding. Ph.D. dissertation, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. ISBN 91-576-4982-0.

Winsa H, Bergsten U (1994) Direct seeding of Pinus sylvestris using microsite preparation and invigorated seed lots of different quality: 2-year results. Can J Forest Res 24: 77–86. https://doi.org/10.1139/x94-012.

Winsa H, Sahlén K (2001) Effects of seed invigoration and microsite preparation on seedling emergence and establishment after direct sowing of Pinus sylvestris L. at different dates. Scand J Forest Res 16: 422–428. https://doi.org/10.1080/02827580152632810.

Total of 71 references.