Impact of varying retention proportions on Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) establishment across planting, direct seeding, and natural regeneration

Lariviere D., Djupström L., Nilsson O. (2025). Impact of varying retention proportions on Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) establishment across planting, direct seeding, and natural regeneration. Silva Fennica vol. 59 no. 3 article id 25007. https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.25007

Highlights

- Site preparation was the most important factor for pine regeneration

- Stand-scale tree retention had little effect, but nearby retention reduced seedlings performances

- Natural regeneration showed the lowest regeneration success

- Planting was most effective even at high retention proportion

- Direct seeding showed promise due to high germination and seedling density

- High tree retention alone cannot ensure regeneration and requires targeted planning.

Abstract

Managing boreal forests while maintaining biodiversity is challenging due to climate change and increasing resource demands. Retention forestry, in which some trees are deliberately left during harvesting, mitigates the negative impacts of clearcutting, but it remains unclear whether regeneration can be ensured as tree retention levels increase. This study assessed Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) regeneration over 4.5 years in the southern boreal zone of Sweden (Effaråsen) under five treatments: four tree retention levels (3%, 10%, 30%, 50%) and a 50% retention treatment with prescribed burning. Mechanical site preparation (MSP) and regeneration methods were key drivers of success in Scots pine forest regeneration. MSP consistently and positively influenced all regeneration variables (height, growth, survival, germination, and recruitment) across planting, seeding, and natural regeneration. Direct seeding produced the highest number of seedlings per hectare, while planting yielded the tallest seedlings with high survival. Natural regeneration produced fewer and smaller seedlings and was insufficient to ensure stand establishment. Stand-scale retention levels generally did not affect regeneration, but retained trees within 20 meters negatively affected the height, growth, and survival of planted and seed-germinated seedlings, likely due to competition, indicating a proximity effect. Burned areas showed greater height and survival, suggesting that prescribed burning enhances regeneration by reducing competition while potentially creating habitat relevant for conservation and specialized species. Overall, the results highlight that retention trees intended for biodiversity have a limited role as seed trees for regeneration, and careful planning is needed to use them for biodiversity purposes without negatively impacting regeneration.

Keywords

boreal forests;

forest management;

mechanical site preparation;

ecosystem services;

browsing;

reestablishment;

retention forestry

-

Lariviere,

The Forestry Research Institute of Sweden (Skogforsk), Uppsala Science Park, SE-751 83 Uppsala, Sweden; Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Southern Swedish Forest Research Centre, P.O. Box 49, SE-230 53 Alnarp, Sweden

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1415-3476

E-mail

delphine.lariviere@slu.se

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1415-3476

E-mail

delphine.lariviere@slu.se

-

Djupström,

The Forestry Research Institute of Sweden (Skogforsk), Uppsala Science Park, SE-751 83 Uppsala, Sweden; Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU), Department of Wildlife, Fish and Environmental Studies, Umeå SE-901 83, Sweden

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4536-7765

E-mail

line.djupstrom@skogforsk.se

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4536-7765

E-mail

line.djupstrom@skogforsk.se

-

Nilsson,

The Forestry Research Institute of Sweden (Skogforsk), Ekebo 2250, SE-268 90 Svalöv, Sweden

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5632-6523

E-mail

oscar.nilsson@skogforsk.se

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5632-6523

E-mail

oscar.nilsson@skogforsk.se

Received 27 February 2025 Accepted 19 October 2025 Published 4 December 2025

Views 6629

Available at https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.25007 | Download PDF

Supplementary Files

1 Introduction

Boreal forests provide essential ecosystem services, including timber and ecological benefits (Brockerhoff et al. 2017). Balancing these services in forest management is challenging. In Sweden, clearcutting and even-aged rotation forestry have historically prioritized timber yields, often at the expense of biodiversity and ecosystem resilience, resulting in homogeneous, conifer-dominated stands (Lindahl et al. 2017; Felton et al. 2020). With increasing attention to sustainability, alternative forestry management approaches are attracting interest (Gustafsson et al. 2020). The Swedish Forestry Act (SFS 1993) emphasizes that timber production and environmental values must be given equal consideration (Gilman and Wu 2023). Coordinating regeneration and environmental planning early in stand development, particularly in Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) forests, may help support both sustainability and future productivity.

Scots pine forests play a vital role in boreal biodiversity, offering habitats for insects, fungi, and birds, including many threatened species (Eide et al. 2020). Structural elements such as long-lived trees and deadwood provide habitat structures that promote overall biodiversity (Kuuluvainen et al. 2017; Santaniello et al. 2017). Additionally, fire is a natural component of Scots pine ecology, historically contributing to both biodiversity and regeneration. It creates substrates like burned wood and tar logs, which are vital for specialized species (Ericsson et al. 2000; Santaniello et al. 2017). Fire may also facilitate regeneration by reducing competition and improving conditions for seedling establishment (Skre et al. 1998; Hille and den Ouden 2004). However, fire suppression and intensive forestry have reduced the occurrence of forest fires and the ecological processes they support. In Sweden, prescribed burning, reintroduced with government support (Ramberg et al. 2018), can replicate natural fire benefits but remains rare. Between 2011 and 2015, less than 2000 hectares of the Swedish forest area were burned annually (Ramberg et al. 2018).

Retention forestry, alongside prescribed burning, provides an additional strategy to enhance the conservation value of Scots pine stands. Retention forestry involves leaving living and dead trees during harvesting to preserve habitat structures that would be lost in clearcutting, maintaining features important for biodiversity such as large trees, deadwood, and canopy cover (Gustafsson et al. 2010). This practice increases the availability of suitable habitats and supports forest biodiversity (Fedrowitz et al. 2014; Rosenvald et al. 2019; Gustafsson et al. 2020; Koivula and Vanha-Majamaa 2020).

Tree retention strategies are often independently implemented, prior to the regeneration phase, while regeneration strategies are determined afterward. On one hand, the presence of retained trees can influence regeneration outcomes by affecting microclimatic conditions and competing for resources, which may in turn impact the effectiveness of certain regeneration methods. On the other hand, retained Scots pine may also serve as seed or shelter trees, supporting natural regeneration in certain contexts (Lula et al. 2024). However, relying on tree retention for seed-based regeneration presents challenges.

Natural regeneration depends on climatic factors that affect flowering and natural seed production. In northern Sweden, insufficient seed production often limits seedling recruitment (Hannerz et al. 2002; Lula et al. 2024). Currently, only 7% of the total regeneration area in Sweden is managed through natural regeneration (The Swedish Forest Agency 2020). In Sweden, planting is the most common regeneration method, followed by natural regeneration and direct seeding (The Swedish Forest Agency 2020). Each method has distinct advantages and limitations.

Planting is reliable but costly (Glöde et al. 2003), while natural regeneration is cost-efficient but dependent on favourable climatic conditions for natural seed production. Direct seeding offers control over seed placement and genetic quality but is frost-sensitive and less commonly applied (Aleksandrowicz-Trzcińska et al. 2018; Ersson 2021). Regardless of the method chosen, browsing pressure from herbivores such as moose and roe deer is a critical factor that can significantly reduce seedling survival and growth, particularly during the vulnerable early stages of regeneration (Bergqvist et al. 2014; Felton et al. 2022).

Mechanical site preparation (MSP) is commonly used to improve seedling growth and survival by reducing competition with ground vegetation (Löf et al. 2012; Thiffault et al. 2013). MSP can also enhance soil mineralization, temperature (Thiffault et al. 2013), water availability (Löf et al. 2012) , and reduce pest damage from the pine weevil (Hylobius abietis L.) by techniques that reverse the soil profile (Örlander and Nilsson 1999). Even though being crucial for successful regeneration, MSP can also result in environmental downsides such as soil erosion and nutrient leaching (Ring and Sikström 2024).

While the benefits and drawbacks of these regeneration methods are well-documented (Pikkarainen et al. 2020; Lula et al. 2021), combining retained trees for biodiversity with seed-trees strategies requires careful consideration. Retained Scots pine can serve as a seed source for natural regeneration, but their presence may both limit initial seedling establishment and create overstorey competition that persists throughout the entire rotation period (Valkonen et al. 2002; Strand et al. 2006; Roberts et al. 2017). Research on regeneration has consistently indicated that the long-term retention of seed trees has a predominantly negative impact on the development of young Scots pine stands, particularly on nutrient-poor sites in Northern Finland and Sweden (Hagner 1965; Sundkvist 1994a, 1994b; Valkonen et al. 2002). As a result, management practices focused on timber production have typically recommended the early removal of seed trees following successful regeneration. Unlike seed trees, retention trees are left for the entire rotation to promote habitat continuity. Understanding how different retention levels, as well as the presence of nearby retained trees, influence regeneration success is crucial for optimizing management strategies.

In this study we tested three regeneration methods (planting, direct seeding, and natural regeneration) in Scots pine stands in northern Sweden (Effaråsen). We evaluated their performance across five levels of tree retention (3%, 10%, 30%, 50%, and 50% combined with prescribed burning) and two site preparation treatments (with or without). Seedling height, number, and growth were measured. We hypothesized that higher levels of tree retention at the stand scale, would reduce seedling height, growth and density due to overstorey competition, while the presence of nearby retained trees within 20 meters would further influence regeneration method performance at the local scale. We also expected that prescribed burning would enhance regeneration method performance, particularly under high retention levels, and that browsing would have a minimal effect on seedling performance outcomes.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Experimental site

Effaråsen is a long-term experimental site established in 2012 to study the effects of fire and forest management on biodiversity and timber production. The site is located near Mora in Dalarna Province, in the southern boreal zone of Sweden (60°58´N, 14°01´E), and is dominated by Scots pine, which accounts for over 95% of the standing volume. The terrain consists of blocky moraine, with a ground vegetation layer dominated by Calluna sp., Empetrum nigrum, Vaccinium vitis-idaea, and Vaccinium myrtillus. Historically, the forest was shaped by frequent, intense fires; the last major one occurred in 1888. The experimental area has undergone one or two thinning and fertilization treatments (Table 1). Prior to harvesting, tree densities ranged from 350 to 800 trees ha–1, although traces of selective cutting were present, the forest had never been clear-cut. Trees from the previous generation were 100–137 years. The experiment includes 24 stands covering 140 ha. For this study, we focused on 15 stands that had been harvested and regenerated. The selected stands have an area ranging from 2.4 to 14.2 ha, with a mean area of 6 ha (Table 1).

| Table 1. Overview of the 15 stands included in the Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) regeneration experiment at Effaråsen (60°58´N, 14°01´E), showing their stand ID, altitude above sea level (msl), stand age, size (ha) , tree density (trees ha–1), mean canopy area (m2) and its standard deviation (SD), year of last fertilisation (year), and treatment which refers to the tree-retention level (%). Canopy area was calculated from pixels representing tree canopy taller than 2 m within a 20-meter radius around each plot and averaged at the stand level. The stand ID refers to the location in the landscape, with “DS-” referring to Djupsjön, “Eff-” to Effaråsen, “ETO-” to Effartjärnen Ost, “ETV-” to Effartjärnen Väst, “KS-” to Kånåsjön, and “TM-” to Tobacksmyren. The number following the stand ID denotes the percentage of tree retention left after clear-cutting (3–50%). | ||||||||

| Stand ID | Altitude (msl) | Age (years) | Size (ha) | Tree ha–1 | Mean canopy area (m2) | SD | Fertilisation (year) | Treatment |

| DS-3 | 378 | 117 | 14 | 488 | 2.36 | 2.6 | 1992, 2000 | Clear-cut with 3 percent tree retention |

| ETO-3 | 382 | 108 | 4 | 212 | 20.01 | 14.1 | 1992 | |

| TM-3 | 405 | 134 | 7 | 539 | 18.89 | 18.2 | 1982, 1992 | |

| ETV-10 | 378 | 137 | 6 | 283 | 29.01 | 29.3 | 1992 | Clear-cut with 10 percent tree retention |

| KS-10 | 391 | 117 | 7 | 488 | 34.55 | 26.4 | 1992, 2000 | |

| TM-10 | 402 | 134 | 7 | 422 | 69.19 | 46.4 | 1982, 1992 | |

| DS-30 | 376 | 117 | 9 | 490 | 317.15 | 140 | 1992, 2000 | Clear-cut with 30 percent tree retention |

| ETO-30 | 385 | 121 | 4 | 414 | 83.77 | 75.1 | 1992 | |

| ETV-30 | 388 | 137 | 4 | 316 | 68.36 | 72.3 | 1992 | |

| EFF-50 | 391 | 111 | 5 | 411 | 213.48 | 138.0 | 1992 | Clear-cut with 50 percent tree retention |

| ETO-50 | 389 | 121 | 6 | 375 | 223.15 | 79.8 | 1992 | |

| KS-50 | 370 | 117 | 4 | 449 | 307.76 | 200.0 | 1992, 2000 | |

| DS-B50 | 374 | 134 | 5 | 401 | 464.42 | 154 | 1992, 2000 | Burning with 50 percent tree retention |

| ETO-B50 | 389 | 121 | 6 | 470 | 84.98 | 30.2 | 1992 | |

| ETV-B50 | 393 | 137 | 2 | 297 | 378.23 | 49.0 | 1992 | |

2.2 Retention trees

The stands selected for the regeneration experiment were harvested in 2012 under five treatments: four tree-retention proportions (3%, 10%, 30%, and 50%) and one 50% retention treatment followed by prescribed burning (50% + Burn, Burn50). Each treatment was represented by three stands (Table 1). Retained trees consisted of living older or larger trees, high-cut stumps, girdled trees and lying dead wood, including both single trees and groups. Selection prioritised Scots pines (Pinus sylvestris) of high conservation value, old, large-diameter (>25 cm Diameter at Breast Height), fire-scarred, or associated with large logs/snags. This selection reflects common pre-clear-cutting practices and spans a gradient from typical industry standards (3%) to high tree retention (50%) (Gustafsson et al. 2012; Martínez Pastur et al. 2020).

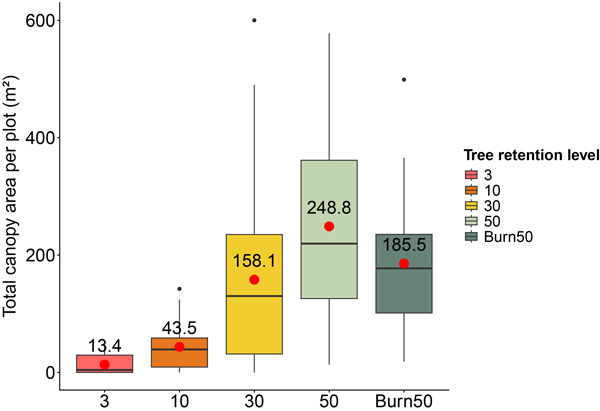

For this study, we examined two aspects of tree retention. First, we considered tree-retention level at the stand scale as a categorical variable representing the share of original living trees left after harvest, the five categories described above. These categories reflect actual tree retention practices on site at the stand scale. Second, we focused on the canopy of retention trees, quantified as the total area of pixels within a 20-meters radius of each regeneration plot (maximum 1257 m2, corresponding to the area of a full 20-meters circle). Canopy area was estimated using a canopy height model (CHM) derived from 2020 Swedish LiDAR data (2 × 2 m pixel size) provided by the Swedish Forest Agency. Pixels with CHM values > 2 meters were assumed to represent tree canopies, although this approach does not distinguish between live and dead crowns. The total canopy area (m2) of these pixels within the 20-meters radius was then summed for each plot to represent the retention canopy surrounding the regeneration plot (Table 1, Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Distribution of the total tree-canopy area per sample plot (squares meters) for each retention levels (x-axis) across all 15 stands. Red points indicate the mean canopy area calculated from the 12 plots within each stand and the three stands replicated for each retention level. Boxes represent the interquartile range (IQR), with whiskers extending to 1.5 times the IQR. The colours denote different tree-retention levels: pink = 3%, orange = 10%, yellow = 30%, light green = 50%, and dark green = Burn + 50% tree retention (stands where 50% of the trees were retained during harvest and the site was subsequently treated with prescribed burning). Tree-canopy density is lower at reduced tree retention levels because fewer trees are retained around the regeneration plots.

2.3 Experimental design

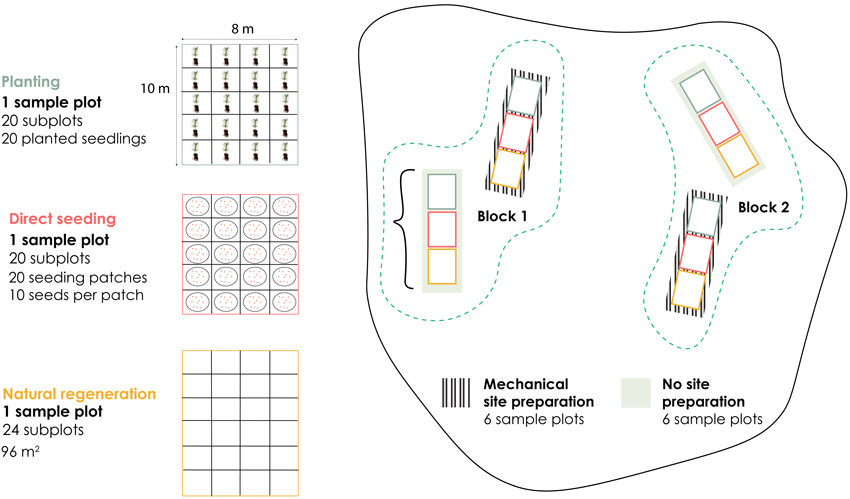

Each stand contained twelve rectangular 8 m × 10 m (80 m2) sample plots, with four plots assigned to each of the three regeneration methods: planting, direct seeding, and natural regeneration. For each regeneration method, half of the sample plots received mechanical site preparation (MSP), while the other half remained untreated. The sample plots were distributed across two main blocks within each stand (Block 1 and Block 2). One planted sample plot consisted of 20 subplots, each containing one seedling. One direct seeding sample plot included 20 subplots, with 10 seeds per subplot sown in patch using a seeding shoe. A natural regeneration sample plot contained 24 subplots covering 96 m2. This design allows comparison of regeneration methods under two contrasting site preparation treatments while maintaining consistent replication across blocks (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Regeneration experimental design for Effaråsen. This illustration shows one stand as an example. Each stand contains twelve 8-m × 10-m sample plots. Each stand contained four sample plots of each of the three regeneration method (planted (blue), direct seeding (red), naturally regenerated (orange)). Half of the sample plot for each regeneration method was mechanically site prepared (hatched), while the other half were left untreated (green). The planted and direct-seeded sample plots were divided into four columns and five rows to form 20 subplots, whereas the naturally regenerated sample plots were divided into four columns and six rows to make 24 subplots.

Harvesting took place during the winter of 2012, while the regeneration experiment and establishment of sample plots were initiated in 2016, following site preparation carried out in autumn 2015. In the planted treatment, seedlings were planted in June 2016, with one plant in each subplot, for a total of 20 plants per sample plot. The seedlings were 1-year-old seedlings from a nursery and measured approximately 12.9 cm with a standard deviation of 2.5 cm and 2.3 mm stem diameter on average. A total of 1200 planted seedlings of the Gnarp provenance were used in the experiment (see Supplementary file A1 for the provenance certificate). Direct seeding sample plots were established simultaneously with the planting plots, using 200 seeds per sample plot. The seeds used for direct seeding had the same provenance and certification as the seedlings used for planting. The naturally regenerated sample plots were left untouched to allow for natural regeneration. However, since site preparation was conducted in the autumn of 2015, the non-site-prepared plots had an additional three growing seasons of natural regeneration prior to the start of the experiment which was acknowledged in the analysis and discussion.

2.4 Field inventory

Each subplot was inventoried five times between 2017 and 2021 (October 2017, June 2019, May 2020, August 2020, and September 2021). For planted seedlings, their status was recorded at each inventory as either “dead” or “alive”. For those classified as alive, the height of each seedling was measured within the subplot. From these data, the mean height and survival proportion (out of the original 20 seedlings) were calculated for each sample plot. In the direct-seeding plots, the number of germinated seedlings was counted, and their height measured and averaged by subplot directly in the field. Plastic markers placed at the time of seeding facilitated identification and helped exclude additional seedlings that might have arisen from natural seed fall. The mean height and germination proportion (out of the 200 original seeds) were then calculated for each sample plot. For natural regeneration, the number of seedlings was counted in the field, and their height was measured and averaged by subplot in the field directly. Using these measurements, the mean height and the total number of recruited seedlings per sample plot were determined.

2.5 Browsing damage

For planted seedlings only, browsing damage was recorded at each inventory time as either browsed (1) or not browsed (0), providing information on the seedling status over time. Browsing was not recorded at the same time each year but rather was synchronized with the regeneration data collection. The overall browsing status was summarised as total browsing pressure, calculated as the sum of browsing events over time on a 0–5 scale. Browsing damage was analysed as a binomial dataset, with “1” indicating that a seedling had been browsed at least once during the five inventories and “0” indicating that it had not been browsed. Browsing categories were also defined for each seedling as follows:

Dead/No browsing: The seedling was dead due to other causes (no browsing score and no height data)

Alive/No browsing: The seedling survived and showed no browsing injury (no browsing score, but still alive).

Dead/Browsed: The seedling was dead and had been browsed at some point during the inventories (browsing score 1–5, but no height data). Browsing may have contributed to the seedling’s death, but causality is not implied.

Alive/Browsed: The seedling survived and was browsed at some point up to inventory 5 (browsing score 1–5, with height data).

2.6 Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed in RStudio using R statistical software (R Core Team 2022). Mean sample plot heights, survival proportion, germination proportion, or recruitment were analysed separately for each inventory time and for the three corresponding regeneration methods (planted, direct seeding, and natural regeneration). Each stand (n = 15, j ) contained 12 sample plots, with four plots assigned to each of the three regeneration methods (n = 60 sample plots per method, i). For each regeneration method, half of the sample plots were mechanically soil-prepared (MSP = 1), and half remained untreated (MSP = 0). The sample plots were further distributed across two blocks (k = 1,2) within each stand (Fig. 2).

Height: Mean seedling height (cm) per sample plot (Mean_Hijk) for plot i in block k of stand j at a given inventory was analysed using linear mixed-effects models (LMER). Fixed effects included tree retention level (ret_lvlijk ; categorical variable with five levels: 3%, 10%, 30%, 50%, and 50% + burn), mechanical site preparation (MSPijk; Boolean variable, 1 = mechanically prepared, 0 = unprepared), and their interaction (ret_lvl × MSP). Random effects accounted for the hierarchical sampling design, with sample plots (i) nested within blocks (k) and stands (j). Mean heights were log-transformed to improve normality and stabilize variance.

P-values for fixed effects were obtained using the Satterthwaite approximation (lmerTest R package) (Kuznetsova et al. 2020). Separate models were fitted for each regeneration method (planted, direct seeding, and natural regeneration) and inventory period (1 to 5). For direct seeding and natural regeneration, models were weighted by the number of measured seedlings per plot so that plots with more observations contributed proportionally to the estimates. The mean seedling height of plot i in block k of stand j at a given inventory x was expressed as:

![]()

where β0 is the intercept, β1 to β3 are fixed effect coefficients, ![]() is the random effect for stand,

is the random effect for stand, ![]() is the random effect for block nested within stand, and

is the random effect for block nested within stand, and ![]() is the residual error.

is the residual error.

Survival/germination/recruitment: Survival (planted) and germination (direct seeding) were expressed as the proportion of seedlings that survived (planted) or germinated (direct seeded) per sample plot i in block k of stand j at a given inventory x (Propijk). Because proportions could include zeros, the response was log-transformed after adding a constant. Fixed and random effects were specified as for the height models. The significance of fixed effects was assessed using Type II Wald F-tests with the Kenward–Roger approximation from the car package. The proportion of survival/germination of plot i in block k of stand j at a given inventory x was expressed as:

![]()

For natural regeneration, seedling counts in each sample plot were analysed using a generalized linear mixed-effects model (GLMM) with a negative binomial distribution and a log link function (glmer.nb), to account for overdispersion. P-values were obtained using Wald χ² tests. Post-hoc comparisons among tree-retention levels and site-preparation treatments were conducted using estimated marginal means from the emmeans package (Lenth et al. 2022). All post-hoc results are presented on the response scale.

Growth: Seedling growth over the five inventories was defined as the difference in mean sample plot height between the first and final inventories, and was analysed using linear mixed-effects models (LMER) for each regeneration method separately as the mean growth per sample plot i in block k of stand j (Growthijk). The objective was not to compare regeneration methods with one another, but to assess the effects of tree retention level and site preparation on growth within each method, recognising that each method has inherent characteristics such as initial biases, differences in starting seedling size, and temporal lags in development.

Fixed effects included tree retention level (ret_lvlijk), mechanical site preparation (MSPijk), and initial mean height (Mean_H1ijk) as a covariate to account for potential differences in growth due to initial seedling size. The forest stand identifier and block were included as nested random effects (vk(j)). P-values for fixed effects were derived using the Satterthwaite method. The mean seedling growth of plot i in block k of stand j was expressed as:

![]()

For direct seeding and natural regeneration, models were additionally weighted by the number of seedlings in the final inventory. Post-hoc comparisons among tree retention levels or site-preparation treatments were conducted using estimated marginal means from the emmeans package (Lenth et al. 2022).

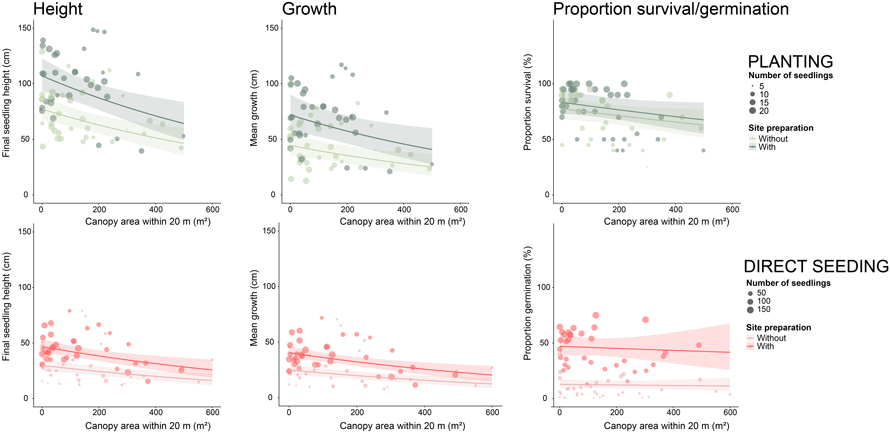

Surrounding canopy area: Final mean seedling height at inventory 5 (H5), final seedling count or survival (S5), and growth (G5) per sample plot were analysed in relation to the total surrounding canopy area within a 20-meters radius of the regeneration plot (Canopy Area) using separate linear mixed-effects models (LMER) from the lme4 package (Kuznetsova et al. 2020) for each regeneration method. Fixed effects included total canopy area per sample plot (sum of 2 × 2 m pixels with canopy height > 20 dm within a 20-meter radius) (CanopyAreaijk) and mechanical site preparation (MSPijk). Random effects accounted for the nested structure of plots within blocks. Because response variables were strictly positive or included zeros, log-transformations were applied to stabilise variance and improve normality. The significance of fixed effects was assessed using Type II Wald F-tests with Kenward–Roger approximated degrees of freedom from the car package. (Yi) of plot i in block k of stand j was expressed as:

![]()

The response variable Yijk represents either final mean seedling height (H5ijk), final seedling count or survival (S5ijk), or total growth (G5ijk), depending on the analysis. The model includes an intercept (β0), fixed effect coefficients for total surrounding canopy area (β1) and mechanical site preparation (β2), and random effects to account for the hierarchical sampling structure. Specifically, ![]() represents the random effect for stand,

represents the random effect for stand, ![]() is the random effect for block nested within stand, and

is the random effect for block nested within stand, and ![]() is the residual error term. For natural regeneration, seedling counts were analysed using generalized linear mixed-effects models (GLMMs) with a Poisson distribution and log link. Post-hoc comparisons among MSP treatments were conducted using estimated marginal means from the emmeans package (Lenth et al. 2022) on the response scale. To visualise the relationship between canopy area and seedling performance, scatter plots were generated for each response variable, with canopy area on the x-axis and seedling height, growth, or survival on the y-axis. Points were jittered to reduce overlap, and regression lines with 95% confidence intervals were overlaid to illustrate the strength and direction of the relationships.

is the residual error term. For natural regeneration, seedling counts were analysed using generalized linear mixed-effects models (GLMMs) with a Poisson distribution and log link. Post-hoc comparisons among MSP treatments were conducted using estimated marginal means from the emmeans package (Lenth et al. 2022) on the response scale. To visualise the relationship between canopy area and seedling performance, scatter plots were generated for each response variable, with canopy area on the x-axis and seedling height, growth, or survival on the y-axis. Points were jittered to reduce overlap, and regression lines with 95% confidence intervals were overlaid to illustrate the strength and direction of the relationships.

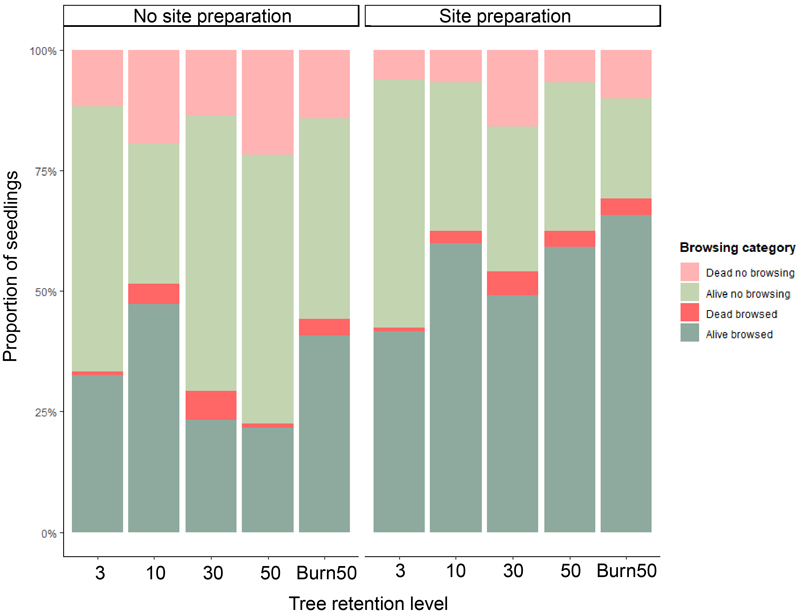

Browsing: Browsing damage was assessed at the subplot level, focusing exclusively on planted seedlings. The variable was treated as binary across the five inventory visits: a value of “1” was assigned to seedlings that were browsed at least once during the experiment, whereas a value of “0” indicated the absence of browsing. The occurrence of browsing damage was analysed using a generalised linear mixed model (GLMM) with a binomial distribution, implemented via the glmer function from the lme4 package (Bates et al. 2015). Additionally, the proportions of seedlings in different browsing categories were analysed at the sample plot level to identify the most prevalent types of browsing within each tree-retention level. These proportions were log-transformed, and linear mixed-effects models (LMER) were fitted using the lmer function from the lme4 package (Bates et al. 2015).

3 Results

3.1 Height

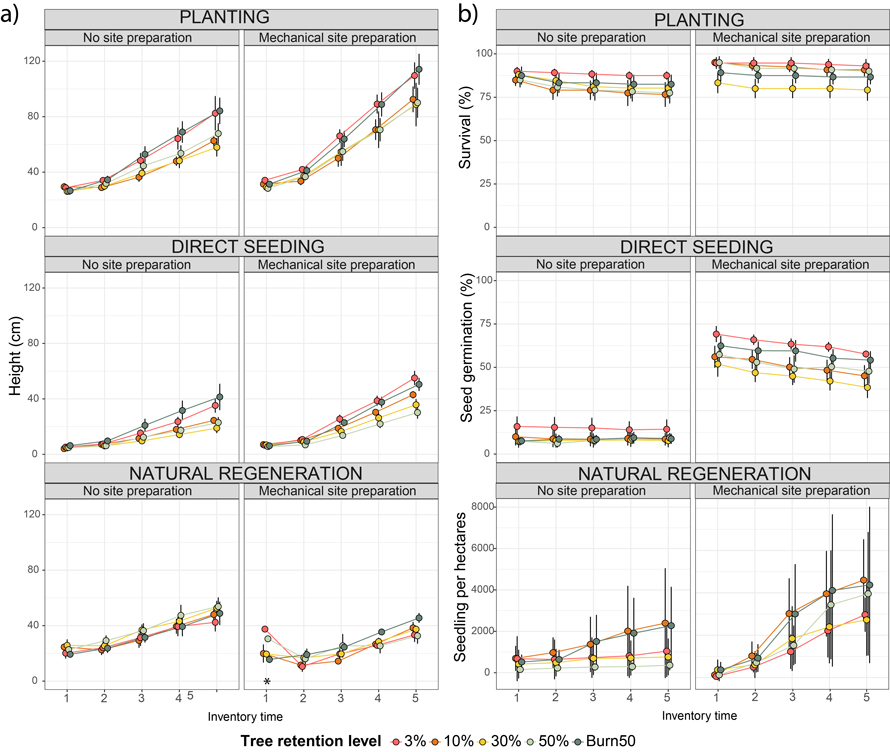

For planted seedlings, mechanical site preparation (MSP) consistently increased seedling height across inventories (Fig. 3), while tree retention level had no effect. At inventory 5, MSP plots reached a mean height of 94.6 cm (SE = 6.47), compared to 67.8 cm (SE = 4.64) in unprepared plots, corresponding to a 39.5% increase in height (Table 2). For direct seeding, MSP influenced seedling height consistently across inventories. While and tree retention levels had a significant effect on direst seeded seedlings height at inventory 5 (Fig. 3). At inventory 5, seedlings in MSP plots reached a mean height of 41.1 cm (SE = 2.06), compared to 25.4 cm (SE = 2.11) in unprepared plots (Table 2). Seedlings in the 3% (41.5 cm, SE = 4.72) and 50% + burn (37.5 cm, SE = 4.82) tree retention levels attained significantly higher final heights than those in the other tree retention levels. For natural regeneration, MSP also influenced seedling height patterns (Fig. 3), but in the opposite direction. Unprepared plots had taller seedlings at the final inventory (48.1 cm, SE = 4.05) than MSP plots (35.6 cm, SE = 2.19) (Table 2), although this comparison may be biased because unprepared plots had a three-season head start before site preparation in autumn 2015. The statistical significance of these trends is presented in Table 3, confirming that MSP significantly affected seedling height across regeneration methods, while tree retention level had a significant effect only in direct seeding. The interaction term was not significant in any case, indicating that the effect of MSP did not vary across retention levels. These results are derived from the mixed-effects model specified in Eq. 1, with complete outputs and parameter estimates available in Suppl. file S1.

Fig. 3. Mean height (a) and survival, seed germination, and seedling recruitment (b) over time for three regeneration methods (Planted (top), Direct Seeding (middle), and Natural Regeneration (bottom)) across tree retention levels (3%, 10%, 30%, 50%, 50% + Burn) with and without mechanical site preparation (MSP). Curves show mean values across five inventories (1 = October 2017, 2 = June 2019, 3 = May 2020, 4 = August 2020, 5 = September 2021), with error bars representing standard errors (SD; n = 10 per retention level and regeneration method). Planted plots included 20 Pinus sylvestris seedlings per plot, direct seeding 200 seeds per plot, and natural regeneration the total number of Pinus sylvestris seedlings per plot converted to seedlings per hectare.

* Comparisons of MSP treatments for natural regeneration should be interpreted cautiously, as plots without MSP had a three-season head start before site preparation. Note that a few naturally regenerated seedlings in MSP plots at inventory 1 were unusually tall and may have been miscounted.

| Table 2. Predicted mean heights (cm) of Pinus sylvestris seedlings across five inventory periods (Inv. 1–5) for three regeneration methods: Planted, Direct-Seeded, and Naturally Regenerated. Values are shown for both plots treated with mechanical site preparation (M) (MSP = 1) and without mechanical site preparation (MSP = 0). µ = predicted mean height on the response scale, SE = standard error, G = grouping letters from pairwise comparisons (different letters indicate significant differences at α = 0.05). Naturally regenerated predicted means should be interpreted with caution due to the presence of significant interactions. | ||||||||||||||||

| Inventory 1 | Inventory 2 | Inventory 3 | Inventory 4 | Inventory 5 | ||||||||||||

| M | µ | SE | G | µ | SE | G | µ | SE | G | µ | SE | G | µ | SE | G | |

| Planted | 1 | 30.4 | 1.25 | a | 37.4 | 1.70 | a | 55.4 | 3.91 | a | 74.5 | 5.20 | a | 94.6 | 6.47 | a |

| 0 | 27.0 | 1.11 | b | 31.3 | 1.42 | b | 42.6 | 3.01 | b | 54.3 | 3.79 | b | 67.8 | 4.64 | b | |

| Direct Seeded | 1 | 6.34 | 0.26 | a | 8.91 | 0.59 | a | 18.7 | 1.02 | a | 29.7 | 1.55 | a | 41.1 | 2.06 | a |

| 0 | 5.13 | 0.37 | b | 6.97 | 0.67 | b | 12.7 | 1.08 | b | 18.8 | 1.53 | b | 25.4 | 2.11 | b | |

| Naturally Regenerated | 1 | 22.5 | 2.15 | a | 12.2 | 1.13 | b | 18.7 | 1.57 | b | 26.3 | 1.90 | b | 35.6 | 2.19 | b |

| 0 | 22.4 | 1.21 | a | 25.6 | 2.65 | a | 31.2 | 3.32 | a | 39.9 | 3.95 | a | 48.1 | 4.05 | a | |

| Table 3. P-values for the effects of tree retention level, site preparation, and their interaction on mean Pinus sylvestris seedling heights across five inventory periods (October 2017, June 2019, May 2020, August 2020, September 2021). P-values were calculated using linear mixed-effects models with the Satterthwaite approximation for degrees of freedom (lmerTest R package). Bold p-values indicate statistically significant effects (p < 0.05). P-values reported as <0.001 are written as 0.001 for clarity. Models were fitted separately for the three regeneration methods: planted seedlings, direct seeding, and natural regeneration. Arrows indicate the direction of the effect: ↑ = positive effect, ↓ = negative effect of site preparation on mean seedling height (MSP = 1 vs MSP = 0). | ||||||

| Inventory 1 | Inventory 2 | Inventory 3 | Inventory 4 | Inventory 5 | ||

| Planted Seedlings | Tree Retention Level | 0.683 | 0.538 | 0.522 | 0.430 | 0.446 |

| Site Preparation | 0.001 (↑) | 0.001 (↑) | 0.001 (↑) | 0.001 (↑) | 0.001 (↑) | |

| Retention Level × Site | 0.742 | 0.946 | 0.880 | 0.949 | 0.960 | |

| Direct Seeded | Tree Retention Level | 0.904 | 0.688 | 0.082 | 0.100 | 0.044 (↑) |

| Site Preparation | 0.005 (↑) | 0.004 (↑) | 0.001 (↑) | 0.001 (↑) | 0.001 (↑) | |

| Retention Level ×Site | 0.500 | 0.702 | 0.364 | 0.164 | 0.153 | |

| Naturally Regenerated | Tree Retention Level | 0.200 | 0.370 | 0.395 | 0.677 | 0.218 |

| Site Preparation | 0.036 (↓) | 0.001 (↓) | 0.001 (↓) | 0.001 (↓) | 0.001 (↓) | |

| Retention Level × Site | 0.040 | 0.683 | 0.313 | 0.084 | 0.147 | |

3.2 Survival/germination/recruitment

For planted seedlings, mechanical site preparation (MSP) increased survival from inventory 2 onwards, while tree retention level had no significant effect (Fig. 3). At the final inventory, survival was higher in MSP plots (87.3%, SE = 3.34; 2185 seedlings ha–1) compared to unprepared plots (79.5%, SE = 3.05; 1990 seedlings ha–1) (Table 4). For direct seeding, MSP also positively influenced germination across all inventories, whereas tree retention level had no effect (Fig. 3). At the final inventory, germination proportions were much higher in MSP plots (47.3%, SE = 5.82; 11 850 seedlings ha–1) than in unprepared plots (6.7%, SE = 0.92; 1675 seedlings ha–1) (Table 4). For natural regeneration, both MSP and tree retention level influenced seedling recruitment from inventory 3 to 5, with a notable interaction (Fig. 3). The 50% tree retention level showed the strongest interaction with MSP, resulting in the highest recruitment (36.07 seedlings, SE = 10.66 with MSP vs. 2.92 seedlings, SE = 1.04 without MSP). MSP significantly increased recruitment across all tree retention levels, with prepared plots (26.79 seedlings, SE = 3.55; 2788 seedlings ha–1) outperforming unprepared plots (7.77 seedlings, SE = 1.11; 808 seedlings ha–1) (Table 4). Among the 64 sample plots, 39 (60.9%) had 20 or fewer seedlings, with a higher proportion in unprepared plots, many of which were empty. The statistical significance of these patterns is summarised in Table 5, confirming the effects of MSP and tree retention level on survival, germination, and recruitment. These results are derived from the mixed-effects model specified in Eq. 1, with complete outputs and parameter estimates available in Suppl. file S2.

| Table 4. Predicted proportion of survival (planted), proportion of germination (direct seeded), or recruitment of Pinus sylvestris seedlings across five inventory periods (Inv. 1–5) for three regeneration methods: Planted, Direct-Seeded, and Natural Regeneration. Values are shown for mechanical site preparation (M) (MSP = 1) and without mechanical site preparation (MSP = 0) plots. µ = predicted mean height on the response scale, SE = standard error, G = grouping letters from pairwise comparisons (different letters indicate significant differences at α = 0.05). Naturally regenerated predicted means should be interpreted with caution due to the presence of significant interactions. | ||||||||||||||||

| Inventory 1 | Inventory 2 | Inventory 3 | Inventory 4 | Inventory 5 | ||||||||||||

| M | µ | SE | G | µ | SE | G | µ | SE | G | µ | SE | G | µ | SE | G | |

| Planted | 1 | 91.2 | 2.31 | a | 89.0 | 2.79 | a | 88.8 | 3.10 | a | 88.0 | 3.23 | a | 87.3 | 3.34 | a |

| 0 | 86.5 | 2.19 | a | 82.5 | 2.59 | b | 80.9 | 2.82 | b | 79.9 | 2.93 | b | 79.5 | 3.05 | b | |

| Direct Seeded | 1 | 57.95 | 7.75 | a | 54.87 | 7.15 | a | 52.04 | 6.57 | a | 50.43 | 6.28 | a | 47.34 | 5.83 | a |

| 0 | 6.35 | 0.97 | b | 5.88 | 0.88 | b | 6.32 | 0.91 | b | 6.63 | 0.93 | b | 6.69 | 0.93 | b | |

| Naturally Regenerated | 1 | 1.02 | 0.28 | b | 5.39 | 0.82 | a | 14.46 | 2.32 | a | 22.15 | 3.24 | a | 26.79 | 3.55 | a |

| 0 | 2.52 | 0.55 | a | 3.69 | 0.58 | b | 5.38 | 0.91 | b | 6.28 | 0.99 | b | 7.77 | 1.11 | b | |

| Table 5. P-values from mixed-effects models testing the effects of tree retention level, site preparation, and their interaction on survival, germination, and recruitment of Pinus sylvestris seedlings across five inventory periods (October 2017, June 2019, May 2020, August 2020, September 2021). P-values were calculated using Type II Wald F-tests with the Kenward–Roger approximation for survival and germination, and Wald χ² tests for recruitment. Bold p-values indicate statistically significant effects (p < 0.05). P-values reported as <0.001 are written as 0.001 for clarity. Columns represent inventory periods, and rows represent the main effects and their interaction (tree retention level × site preparation) on survival (proportion of 20 planted seedlings), germination (proportion of 200 seeds), and recruitment (number of seedlings per plot). Arrows indicate the direction of the effect: ↑ = positive effect, ↓ = negative effect of site preparation on the proportion of survival/germination or seedling recruitment (MSP = 1 vs MSP = 0). | ||||||

| Inventory 1 | Inventory 2 | Inventory 3 | Inventory 4 | Inventory 5 | ||

| Planted seedlings % survival | Tree Retention Level | 0.808 | 0.751 | 0.721 | 0.779 | 0.798 |

| Site Preparation | 0.079 | 0.018 (↑) | 0.006 (↑) | 0.008 (↑) | 0.011 (↑) | |

| Retention Level × Site | 0.359 | 0.222 | 0.494 | 0.512 | 0.416 | |

| Direct seeded % Germination | Tree Retention Level | 0.493 | 0.373 | 0.387 | 0.437 | 0.455 |

| Site Preparation | 0.001 (↑) | 0.001 (↑) | 0.001 (↑) | 0.001 (↑) | 0.001 (↑) | |

| Retention Level × Site | 0.716 | 0.749 | 0.858 | 0.944 | 0.938 | |

| Natural regeneration Recruitment | Tree Retention Level | 0.267 | 0.099 | 0.077 | 0.006 | 0.002 |

| Site Preparation | 0.001 (↓) | 0.693 | 0.001 (↑) | 0.001 (↑) | 0.001 (↑) | |

| Retention Level × Site | 0.004 | 0.029 | 0.008 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

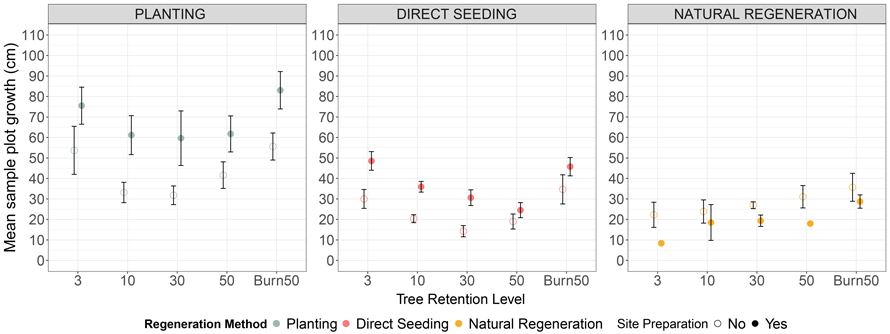

3.3 Growth

Mechanical site preparation (MSP) increased mean sample plot growth for planted seedlings across all tree retention levels (Fig. 4). A positive estimate of 20.89 indicates that, on average, site-prepared (MSP) plots grew approximately 21 cm more than untreated plots over the five inventories, after accounting for retention level and initial seedling height. In contrast, retention level had no significant effect on total growth. For direct seeding, MSP enhanced growth across all tree retention levels, with the highest growth observed at 3% tree retention with MSP (44.7 cm, SE = 4.42), followed by 50% + Burn with MSP (41.8 cm, SE = 4.59) and 3% without MSP and 10% with MSP (both 32.9 cm, SE = 4.78, 4.59). Growth was lowest at 50% tree retention without MSP (15.1 cm, SE = 5.03) and 30% tree retention without MSP (15.9 cm, SE = 4.99) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Mean height difference from inventory 5 to inventory 1 (± standard error) of Pinus sylvestris seedlings under different regeneration methods (Natural regeneration, Planting, and Direct seeding) across tree retention levels (3%, 10%, 30%, 50%, and Burn50) and site preparation conditions (No site preparation vs. Site preparation).

* The natural regeneration treatment with no site preparation needs to be interpreted with care as the seedlings started to regenerate 3 years prior the site preparation was carried out.

For natural regeneration, MSP influenced growth (Fig. 4), with slightly higher mean growth in unprepared plots (28.1 cm, SE = 3.48) than in MSP plots (21.4 cm, SE = 3.31). Tree retention level had no clear effect. These results are derived from the mixed-effects model specified in Eq. 3, with complete outputs and parameter estimates available in Suppl. file S3.

3.4 Surrounding canopy area

For planted seedlings, both Mechanical site preparation (MSP) and the total canopy area within a 20 m radius of the regeneration plot significantly affected height and growth, while only MSP improved survival (Table 6). Height decreased steadily with increasing canopy area, showing that canopy still limits growth even when site preparation is applied, while MSP consistently enhanced height (Fig. 5). For direct-seeded seedlings, MSP strongly increased height, growth, and proportion of seed germination, whereas the total canopy area within a 20 m radius only influenced height and growth (Table 6). Direct-seeded seedlings surrounded by high mean canopy area within a 20 m radius of the regeneration plot without MSP had lower height and growth than those in low-canopy plots without preparation, highlighting the importance of MSP for direct-seeded seedlings (Fig. 5). For naturally regenerated seedlings, MSP substantially increased recruitment, but seedlings in MSP plots were smaller in height (Table 6) because they established later, after mechanical soil preparation in 2015, whereas seedlings in non-MSP plots had a three-year head start since 2012. The mean canopy area within a 20 m radius had no significant effect, indicating that site preparation is the main driver of establishment when regeneration occurs later. Complete model outputs and estimates are available in Suppl. file S4.

| Table 6. P-values from mixed-effects models testing the effects of total tree canopy area, tree retention level, and site preparation on mean sample plot seedling height (Height), sample plot survival (out of the 20 original seedlings)/germination proportion (out of the 200 original seeds)/Recruitment (number of seedlings per sample plot) (Surv), and mean sample plot growth (growth). Significant effects are highlighted in bold, with p-values less than 0.05 indicating statistically significant relationships. P-values reported as <0.001 are written as 0.001 for clarity. | ||||

| Height | Surv | Growth | ||

| Planted Seedlings | Canopy area | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.010 |

| Site Preparation | 0.001 | 0.028 | 0.001 | |

| Direct Seeded | Canopy area | 0.001 | 0.673 | 0.001 |

| Site Preparation | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Naturally Regenerated | Canopy area | 0.714 | 0.244 | 0.293 |

| Site Preparation | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

* The natural regeneration treatment with no site preparation needs to be interpreted with care as the seedlings started to regenerate 3 years prior the site preparation was carried out. View larger in new window/tab.

3.5 Browsing damage

Over the course of the five inventories, 23.4% of the 1192 planted seedlings were browsed once, 15.9% twice, 6.5% three times and 1.2% four times; the rest (52.9%) remained unbrowsed. The actual potential death (non-confirmed) by browsing accounted for only 3% of all seedlings. Based on the analysis of deviance using Type III Wald Chi-square tests, tree retention levels were not a statistically significant predictor of total browsing damage after five inventories (χ2 = 3.531, p = 0.473). However, MSP seedlings were more browsed compared to non-MSP seedlings (χ2 = 24.559, p < 0.00). Similar results were found when evaluating the browsing categories (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Proportion of Pinus sylvestris seedlings for each browsing level from the 1192 seedlings originally planted and their browsing status after 5 growing seasons. The dark red and dark green bars represent the browsed seedlings, whereas the light red and light green represent the non-browsed seedlings. Red bars are dead seedlings, whereas green bars are live seedlings after 5 years. Alive seedlings are heavily browsed but still alive. Categories are as follows: (1) Plants that died from causes other than browsing; (2) Plants that survived without any browsing injuries; (3) Plants that were browsed but died, either due to browsing or other causes; (4) Plants that were browsed but survived.

4 Discussion

Regenerating Scots pine in boreal forests remains a silvicultural challenge, particularly under retention forestry systems that aim to integrate ecological values with timber production. While mechanical site preparation (MSP), regeneration method selection, and tree retention are all known to influence regeneration success, their combined application in operational settings is less frequently evaluated. This study contributes to that understanding by assessing how regeneration outcomes vary across different methods and site preparation treatments, and how they are affected by the presence of retained trees. Our findings offer insights into how regeneration strategies can be better aligned with both silvicultural and ecological objectives.

4.1 Mechanical site preparation

Our results clearly demonstrate that MSP is the most influential factor for successful Scots pine establishment, significantly enhancing seedling height, growth, and survival across all regeneration methods. In our study, seedlings in MSP plots were approximately 20 cm taller and exhibited high survival just one year after treatment. The benefits of MSP are well established, including improved soil conditions, reduced competition, and increased nutrient availability (Nilsson et al. 2010; Sikström et al. 2020; Häggström et al. 2021). Seedlings in no-MSP plots also exhibited high survival, likely due to the three-year interval between harvest and planting, which may have reduced pine weevil pressure, a threat that MSP has been shown to mitigate (Örlander and Nilsson 1999; Hjelm et al. 2019). Despite the benefits of MSP in the natural regeneration plots, the seedling heights and recruitments were minimal. Natural regeneration produced taller seedlings in unprepared plots than in MSP plots, likely because of earlier germination and establishment. However, this head start in establishment did not translate into superior performance when compared with planted seedlings. Recruitment success was strongly influenced by site preparation, yet overall seedling density remained well below the levels reported in studies where site preparation and overstorey management were optimally integrated (Karlsson 2000; Lula et al. 2024).

4.2 Regeneration methods

The choice of regeneration method significantly influences stand development. Natural regeneration is inherently uncertain, being highly dependent on climatic conditions, seed production, and the reproductive ecology of Scots pine (Sarvas 1962; Hagner 1965; Leikola et al. 1982). Planting and direct seeding offer safer, more reliable ways to secure regeneration through seeds or seedlings. Planting one-year-old seedlings resulted in the tallest individuals after five growing seasons, even with high tree retention proportion, confirming previous findings that planting is the most effective short-term strategy for Scots pine regeneration (Hjelm et al. 2019; Sikström et al. 2020). Planted seedlings can bypass the vulnerable early stages of seed dispersal and germination, starting as established plants with a clear advantage in survival and growth. Direct seeding, while more cost-effective, produced significantly shorter seedlings due to the time required for germination and establishment. Although it resulted in high seedling densities, the distribution was uneven, which may affect the representativeness of the results as presented in other studies (Wennström 2001; Miina and Saksa 2008). Both planting and direct seeding may also be the opportunity to use genetically improved material, which may outperform local genotypes in terms of growth, form, and pest resistance (Rosvall et al. 2001; Haapanen et al. 2016).

Although primarily evaluated for silvicultural outcomes, regeneration methods also carry important ecological implications. Natural regeneration, despite its unpredictability, enhances structural diversity by promoting uneven-aged stands and heterogeneous microhabitats, which support biodiversity and ecosystem resilience (Lula et al. 2024; Miettinen et al. 2024). In contrast, planting genetically selected trees often results in uniform stand structures, reducing habitat heterogeneity and potentially weakening ecological resilience (Haapanen et al. 2016; Masternak and Cymerys 2025). Studies in Finland and Sweden show that manipulation of the overstorey in the form of thinning or gap cutting combined with site preparation can lead to successful regeneration and heterogeneous stand structures (Karlsson 2000; Lula et al. 2024; Miettinen et al. 2024). However, its success is strongly influenced by seasonal variation, site-specific conditions, and the ecological stage of the regenerating pine. At Effaråsen for example, our findings confirms that regeneration success is often compromised when retention efforts are not spatially and temporally coordinated with regeneration planning. Simply leaving a proportion of retention trees as seed trees without considering their placement, timing, or ecological function can lead to poor outcomes due to inadequate seed dispersal, competition, or mismatched site conditions. Effective retention must be strategically aligned with regeneration goals to ensure ecological compatibility and long-term forest resilience for all regeneration methods, and especially for natural regeneration, where retention trees are expected to serve as seed sources (Häggström et al. 2024; Miettinen et al. 2024).

4.3 Tree retention effects

Our results show that current practical stand-scale tree retention strategies have little effect on local Scots pine regeneration but nearby retained trees within 20 meters negatively affected seedling performance. Retention is typically implemented at the stand scale prior to regeneration and often combines various elements such as deadwood, snags, living trees, and tree groups. The lack of a stand-scale effect likely reflects the type of retention influencing seedlings, as the canopy area within 20 meters of regeneration plots is most likely representing living trees. This aligns with previous research showing that seedling performance is often reduced near retained trees due to above- and below-ground competition (Jakobsson and Elfving 2004; Elfving and Jakobsson 2006; Strand et al. 2006). Above-ground competition, especially shading from tree crowns, likely played a significant role in suppressing seedling development. The influence of retained trees typically extends 6–10 metres from the stem base depending on tree species (Valkonen et al. 2002; Lariviere et al. 2023). Nearby retention can reduce light and intensify competition for water and nutrients, especially in nutrient-poor soils (Axelsson et al. 2014).

Both the type and spatial placement of retained trees are key for effective regeneration and conservation outcomes. Trees with large crowns and high seed production are particularly beneficial for natural regeneration (Pukkala and Kolström 1992; Karlsson 2000; Simonsen 2013). While large old Scots pine supports regeneration objectives and considered as high biodiversity value, relying solely on one species may limit biodiversity benefits. A mixture of species enhances habitat complexity and supports a broader range of organisms (Gamfeldt et al. 2013; Jucker et al. 2014) , while also carefully considering potential interspecific competition.

Strategic spatial and temporal placement of retention trees further enhances their ecological and silvicultural value. Evenly dispersed trees have minimal impact on productivity (Jakobsson and Elfving 2004) while contributing to landscape connectivity and microhabitat diversity (Rocha et al. 2021). It is important to distinguish retention trees from seed trees: retention trees remain on site throughout the rotation, contributing primarily to long-term ecological and structural stability, whereas seed trees can be clustered to maximize seed dispersal and may be removed once regeneration is established.

Overall, our findings indicate that it is the local influence of nearby living trees, rather than the overall amount of stand-scale retention, that most strongly limits Scots pine regeneration. Competition for light, water, and nutrients from retained living trees within about 20 m reduced seedling performance, while other retained elements such as deadwood or snags were unlikely to exert similar pressure. Effective retention planning should therefore focus on the fine-scale distribution of living trees, prioritizing individuals that unofficially contribute to the regeneration while avoiding excessive shading or below-ground competition near regeneration areas.

4.4 Additional factors affecting regeneration

Although not central to the study’s primary objectives, two additional findings offer relevant insights.

Browsing of planted Scots pine seedlings was widespread, with 47.1% of seedlings browsed at least once, and higher browsing pressure observed in MSP plots (60%) compared to non-MSP plots (32%). Despite this, mortality due to browsing was low (3%). Nursery-grown seedlings are attractive to herbivores due to higher nutrient content and lower lignin concentrations (Bergquist et al. 2003; Novaes et al. 2010), but their faster growth may allow them to escape the vulnerable browsing stage more quickly (Bergström and Bergqvist 1997). At Effaråsen, although some seedlings were browsed, this had no measurable impact on survival or regeneration outcomes, indicating that browsing did not influence the results of our study. We did not measure browsing on other regeneration methods, but these dynamics underline the importance of considering herbivore pressure in regeneration planning, particularly in landscapes with high browsing activity (Felton et al. 2022).

Prescribed burning, used as a complementary treatment to MSP, showed promising results for Scots pine regeneration. In plots with 50% tree retention, burning improved seedling height, survival, and germination, suggesting that fire can help reconcile regeneration and conservation objectives. Fire reduces competition by clearing vegetation and enhances nutrient turnover (Certini 2005; Eriksson et al. 2013), while also creating microhabitats and substrates essential for many forest species (Siitonen 2001; Santaniello et al. 2017).However, prescribed burning is costly and must be carefully managed to avoid excessive canopy mortality and disruption of belowground diversity (Keeley et al. 2008; Pec et al. 2020). The positive effects observed in this study likely stem from reduced competition and increased nutrient availability following fire-induced tree mortality. Additionally, the limited replication of the burning treatment makes it difficult to examine its effects thoroughly. Therefore, caution is needed when interpreting the results.

4.5 Integrating silviculture and conservation

Overall, our study demonstrates that careful planning of regeneration methods and retention strategies is crucial for achieving both silvicultural success and ecological objectives in boreal Scots pine stands. Mechanical site preparation (MSP) is essential for Scots pine regeneration, yet it can negatively affect soil communities (Jones et al. 2003; Ring and Sikström 2024) a and destroy critical habitat for wood-dependent organisms (Santaniello et al. 2016). Planting generally produces the most reliable results, and the overall amount of retained trees at the stand scale has little effect on growth or survival. Seeding can succeed, but seedlings are smaller and more sensitive to nearby retained trees due to their developmental stage and seed germination requirements. Natural regeneration performed poorly at Effaråsen, as it relied solely on retention trees as seed sources and lacked careful planning.

High retention is feasible in some scenarios, particularly with planting, which still showed reasonable height and survival despite high tree retention levels. However, while regeneration and retention are feasible at establishment, future competition with retained trees may reduce growth or survival. These results emphasize the importance of strategically planning retention from the establishment phase, since retained trees remain on site throughout the rotation and cannot be removed like seed trees.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support of Michael Krook, field technician at Skogforsk, for his role in data collection, which contributed to the outcomes of this research. The authors also acknowledge the support of Jon Ahlinder (Skogforsk) and Adam Flöhr (SLU, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences) for their assistance in the statistical analyses and processes.

Funding

The data collection was partially financed by the European program Landsbygdsprogrammet (LBP), but the study was financially supported by the FRAS II research program (Framtidens skogsskötsel i södra Sverige / Future Forest Management in Southern Sweden).

Authors’ contributions

Delphine Lariviere led the data analysis and manuscript writing. Line Djupström contributed to the conceptual development and project coordination. Oscar Nilsson provided supporting analyses for related work. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version.

Declaration of openness of research materials, data, and code

This article will be published as open access under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-SA 4.0). All data used in the study are openly available through the Swedish National Data Service (SND) at: https://doi.org/10.5878/4d05-qn08. The statistical analyses were conducted using R, and model specifications are described in the Methods section to ensure transparency and reproducibility.

References

Aleksandrowicz-Trzcińska M, Drozdowski S, Studnicki M, Żybura H (2018) Effects of site preparation methods on the establishment and natural-regeneration traits of Scots pines (Pinus sylvestris L.) in Northeastern Poland. Forests 9, article id 717. https://doi.org/10.3390/f9110717.

Axelsson EP, Lundmark T, Högberg P, Nordin A (2014) Belowground competition directs spatial patterns of seedling growth in boreal pine forests in Fennoscandia. Forests 5: 2106–2121. https://doi.org/10.3390/f5092106.

Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S, Christensen RHB, Singmann H, Dai B, Scheipl F, Grothendieck G (2015) Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw 67: 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01.

Bergquist J, Örlander G, Nilsson U (2003) Interactions among forestry regeneration treatments, plant vigour and browsing damage by deer. New For 25: 25–40. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022378908827.

Bergqvist G, Bergström R, Wallgren M (2014) Recent browsing damage by moose on Scots pine, birch and aspen in young commercial forests – effects of forage availability, moose population density and site productivity. Silva Fenn 48, article id 1077. https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.1077.

Bergström R, Bergqvist G (1997) Frequencies and patterns of browsing by large herbivores on conifer seedlings. Scand J For Res 12: 288–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/02827589709355412.

Brockerhoff EG, Barbaro L, Castagneyrol B, Forrester DI, Gardiner B, González-Olabarria JR, Lyver POB, Meurisse N, Oxbrough A, Taki H (2017) Forest biodiversity, ecosystem functioning and the provision of ecosystem services. Biodivers Conserv 26: 3005–3035. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-017-1453-2.

Certini G (2005) Effects of fire on properties of forest soils: a review. Oecologia 143: 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-004-1788-8.

Eide W, Ahrné K, Bjelke U, Nordström S, Ottosson E, Sandström J, Sundberg S (2020) Tillstånd och trender för arter och deras livsmiljöer – rödlistade arter i Sverige 2020. SLU Artdatabanken, Uppsala. ISBN 978-91-87853-55-5.

Elfving B, Jakobsson R (2006) Effects of retained trees on tree growth and field vegetation in Pinus sylvestris stands in Sweden. Scand J For Res 21: 29–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/14004080500487250.

Ericsson S, Östlund L, Axelsson A-L (2000) A forest of grazing and logging: deforestation and reforestation history of a boreal landscape in central Sweden. New For 19: 227–240. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006673312465.

Eriksson A-M, Olsson J, Jonsson BG, Toivanen S, Edman M (2013) Effects of restoration fire on deadwood heterogeneity and availability in three Pinus sylvestris forests in Sweden. Silva Fenn 47, article id 954. https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.954.

Ersson BT (2021) Mechanized direct seeding: good practice examples in optimization of forest operations. Net4Forest. https://res.slu.se/id/publ/112487.

Fedrowitz K, Koricheva J, Baker SC, Lindenmayer DB, Palik B, Rosenvald R, Beese W, Franklin JF, Kouki J, Macdonald E, Messier C, Sverdrup-Thygeson A, Gustafsson L (2014) Can retention forestry help conserve biodiversity? A meta-analysis. J Appl Ecol 51: 1669–1679. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.12289.

Felton A, Löfroth T, Angelstam P, Gustafsson L, Hjältén J, Felton AM, Simonsson P, Dahlberg A, Lindbladh M, Svensson J, Nilsson U, Lodin I, Hedwall PO, Sténs A, Lämås T, Brunet J, Kalén C, Kriström B, Gemmel P, Ranius T (2020) Keeping pace with forestry: multi-scale conservation in a changing production forest matrix. Ambio 49: 1050–1064. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-019-01248-0.

Felton AM, Hedwall P-O, Felton A, Widemo F, Wallgren M, Holmström E, Löfmarck E, Malmsten J, Wam HK (2022) Forage availability, supplementary feed and ungulate density: associations with ungulate damage in pine production forests. For Ecol Manag 513, article id 120187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2022.120187.

Gamfeldt L, Snall T, Bagchi R, Jonsson M, Gustafsson L, Kjellander P, Ruiz-Jaen MC, Froberg M, Stendahl J, Philipson CD, Mikusinski G, Andersson E, Westerlund B, Andren H, Moberg F, Moen J, Bengtsson J (2013) Higher levels of multiple ecosystem services are found in forests with more tree species. Nat Commun 4, article id 1340. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2328.

Gilman J, Wu J (2023) The interactions among landscape pattern, climate change, and ecosystem services: progress and prospects. Reg Environ Change 23, article id 67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-023-02060-z.

Glöde D, Hannerz M, Eriksson B (2003) Economic comparison of different regeneration methods – ekonomisk jämförelse av olika föryngringsmetoder. Arbetsrapport 557, Skogforsk. https://www.skogforsk.se/contentassets/e29dbb16bfa340b187bed0646ad338f2/arbetsrapport-557-2003.pdf.

Gustafsson L, Baker SC, Bauhus J, Beese WJ, Brodie A, Kouki J, Lindenmayer DB, Lõhmus A, Pastur GM, Messier C, Neyland M, Palik B, Sverdrup-Thygeson A, Volney WJA, Wayne A, Franklin JF (2012) Retention forestry to maintain multifunctional forests: a world perspective. BioScience 62: 633–645. https://doi.org/10.1525/bio.2012.62.7.6.

Gustafsson L, Hannerz M, Koivula M, Shorohova E, Vanha-Majamaa I, Weslien J (2020) Research on retention forestry in Northern Europe. Ecol. Process 9, article id 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-019-0208-2.

Gustafsson L, Kouki J, Sverdrup-Thygeson A (2010) Tree retention as a conservation measure in clear-cut forests of northern Europe: a review of ecological consequences. Scand J For Res 25: 295–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/02827581.2010.497495.

Haapanen M, Hynynen J, Ruotsalainen S, Siipilehto J, Kilpeläinen M-L (2016) Realised and projected gains in growth, quality and simulated yield of genetically improved Scots pine in southern Finland. Eur J For Res 135: 997–1009. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10342-016-0989-0.

Häggström B, Domevscik M, Öhlund J, Nordin A (2021) Survival and growth of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) seedlings in north Sweden: effects of planting position and arginine phosphate addition. Scand J For Res 36: 423–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/02827581.2021.1957999.

Häggström B, Gundale MJ, Nordin A (2024) Environmental controls on seedling establishment in a boreal forest: implications for Scots pine regeneration in continuous cover forestry. Eur J For Res 143: 95–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10342-023-01609-1.

Hagner S (1965) Yield of seed, choice of seed trees, and seedling establishment in experiments with natural regeneration. Studia Forestalia Suecica 27, Skogshögskolan, Stockholm. https://res.slu.se/id/publ/125316.

Hannerz M, Almqvist C, Hörnfeldt R (2002) Timing of seed dispersal in Pinus sylvestris stands in central Sweden. Silva Fenn 36: 754–765. https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.518.

Hille M, den Ouden J (2004) Improved recruitment and early growth of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) seedlings after fire and soil scarification. Eur J For Res 123: 213–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10342-004-0036-4.

Hjelm K, Nilsson U, Johansson U, Nordin P (2019) Effects of mechanical site preparation and slash removal on long-term productivity of conifer plantations in Sweden. Can J For Res 49: 1311–1319. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjfr-2019-0081.

Jakobsson R, Elfving B (2004) Development of an 80-year-old mixed stand with retained Pinus sylvestris in Northern Sweden. For Ecol Manag 194: 249–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2004.02.030.

Jones MD, Durall DM, Cairney JWG (2003) Ectomycorrhizal fungal communities in young forest stands regenerating after clearcut logging. New Phytol 157: 399–422. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00698.x.

Jucker T, Bouriaud O, Avacaritei D, Coomes DA (2014) Stabilizing effects of diversity on aboveground wood production in forest ecosystems: linking patterns and processes. Ecol Lett 17: 1560–1569. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12382.

Karlsson C (2000) Effects of release cutting and soil scarification on natural regeneration in Pinus sylvestris shelterwoods. Doctoral thesis, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. ISBN 91-576-5871-4.

Keeley JE, Brennan T, Pfaff AH (2008) Fire severity and ecosystem responses following crown fires in California shrublands. Ecol Appl 18: 1530–1546. https://doi.org/10.1890/07-0836.1.

Koivula M, Vanha-Majamaa I (2020) Experimental evidence on biodiversity impacts of variable retention forestry, prescribed burning, and deadwood manipulation in Fennoscandia. Ecol Process 9, article id 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-019-0209-1.

Kuuluvainen T, Aakala T, Várkonyi G (2017) Dead standing pine trees in a boreal forest landscape in the Kalevala National Park, northern Fennoscandia: amount, population characteristics and spatial pattern. For Ecosyst 4, article id 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40663-017-0098-7.

Kuznetsova A, Brockhoff PB, Christensen RHB (2020) lmertest package: tests in linear mixed effects models. J Stat Softw 82: 1–26. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v082.i13.

Lariviere D, Holmström E, Petersson L, Djupström L, Weslien J (2023) Ten years after: release cutting around old oaks still affects oak vitality and saproxylic beetles in a Norway spruce stand. Agric For Entomol 25: 416–426. https://doi.org/10.1111/afe.12563.

Leikola M, Raulo J, Pukkala T (1982) Predictions of the variations of the seed crop of Scots pine and Norway spruce. Folia For 537: 1–43. https://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:951-40-0593-7.

Lenth R, Singmann H, Love J, Buerkner P, Herve M (2022) R package ‘emmeans’, version 1.8.3. The R Fundation.

Lindahl KB, Sténs A, Sandström C, Johansson J, Lidskog R, Ranius T, Roberge J-M (2017) The Swedish forestry model: more of everything? For Policy Econ 77: 44–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2015.10.012.

Löf M, Dey DC, Navarro RM, Jacobs DF (2012) Mechanical site preparation for forest restoration. New For 43: 825–848. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11056-012-9332-x.

Lula M, Domevscik M, Hjelm K, Andersson M, Johansson U, Wallertz K, Nilsson U (2024) Recruitment dynamics of naturally regenerated Scots pine under different overstorey densities in southern Sweden. Scand J For Res 39: 402–410. https://doi.org/10.1080/02827581.2024.2443058.

Lula M, Trubins R, Ekö PM, Johansson U, Nilsson U (2021) Modelling effects of regeneration method on the growth and profitability of Scots pine stands. Scand J For Res 36: 263–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/02827581.2021.1908591.

Martínez Pastur GJ, Vanha-Majamaa I, Franklin JF (2020) Ecological perspectives on variable retention forestry. Ecol Process 9, article id 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-020-0215-3.

Masternak K, Cymerys P (2025) Comparison of genetic variability and growth characteristics of naturally regenerated and planted Scots pine. Folia For Pol Ser A For 67: 76–85. https://doi.org/10.2478/ffp-2025-0008.

Miettinen J, Hallikainen V, Valkonen S, Hökkä H, Hyppönen M, Rautio P (2024) Natural regeneration and early development of Scots pine seedlings after gap cutting in northern Finland. Scand J For Res 39: 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/02827581.2024.2303022.

Miina J, Saksa T (2008) Predicting establishment of tree seedlings for evaluating methods of regeneration for Pinus sylvestris. Scand J For Res 23: 12–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/02827580701779595.

Nilsson U, Luoranen J, Kolström T, Örlander G, Puttonen P (2010) Reforestation with planting in northern Europe. Scand J For Res 25: 283–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/02827581.2010.498384.

Novaes E, Kirst M, Chiang V, Winter-Sederoff H, Sederoff R (2010) Lignin and biomass: a negative correlation for wood formation and lignin content in trees. Plant Physiol 154: 555–561. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.110.161281.

Örlander G, Nilsson U (1999) Effect of reforestation methods on pine weevil (Hylobius abietis) damage and seedling survival. Scand J For Res 14: 341–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/02827589950152665.

Pec GJ, Simard SW, Cahill JF, Karst J (2020) The effects of ectomycorrhizal fungal networks on seedling establishment are contingent on species and severity of overstorey mortality. Mycorrhiza 30: 173–183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00572-020-00940-4.

Pikkarainen L, Luoranen J, Kilpeläinen A, Oijala T, Peltola H (2020) Comparison of planting success in one-year-old spring, summer and autumn plantings of Norway spruce and Scots pine under boreal conditions. Silva Fenn 54, article id 10243. https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.10243.

Pukkala T, Kolström T (1992) A stochastic spatial regeneration model for Pinus sylvestris. Scand J For Res 7: 377–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/02827589209382730.

R Core Team (2022) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna. https://www.R-project.org/.

Ramberg E, Strengbom J, Granath G (2018) Coordination through databases can improve prescribed burning as a conservation tool to promote forest biodiversity. Ambio 47: 298–306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-017-0987-6.

Ring E, Sikström U (2024) Environmental impact of mechanical site preparation on mineral soils in Sweden and Finland – a review. Silva Fenn 58, article id 23056. https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.23056.

Roberts MW, D’Amato AW, Kern CC, Palik BJ (2017) Effects of variable retention harvesting on natural tree regeneration in Pinus resinosa (red pine) forests. For Ecol Manag 385: 104–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2016.11.025.

Rocha ÉGd, Brigatti E, Niebuhr BB, Ribeiro MC, Vieira MV (2021) Dispersal movement through fragmented landscapes: the role of stepping stones and perceptual range. Landsc Ecol 36: 3249–3267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-021-01310-x.

Rosenvald R, Lõhmus P, Rannap R, Remm L, Rosenvald K, Runnel K, Lõhmus A (2019) Assessing long-term effectiveness of green-tree retention. For Ecol Manag 448: 543–548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2019.06.034.

Rosvall O, Jansson G, Andersson B, Ericsson T, Karlsson B, Sonesson J, Stener L (2001) Genetiska vinster i nuvarande och framtida fröplantager och klonblandningar. [Genetic gain from present and future seed orchards and clone mixes]. Redogörelse nr. 1, Skogforsk, Uppsala.

Santaniello F, Djupström LB, Ranius T, Rudolphi J, Widenfalk O, Weslien J (2016) Effects of partial cutting on logging productivity, economic returns and dead wood in boreal pine forest. For Ecol Manag 365: 152–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2016.01.033.

Santaniello F, Djupström LB, Ranius T, Weslien J, Rudolphi J, Thor G (2017) Large proportion of wood dependent lichens in boreal pine forest are confined to old hard wood. Biodivers Conserv 26: 1295–1310. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-017-1301-4.

Sarvas R (1962) Investigations on the flowering and seed crop of Pinus sylvestris. Commun Inst For Fenn 53: 1–198. http://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi-metla-201207171085.

Siitonen J (2001) Forest management, coarse woody debris and saproxylic organisms: Fennoscandian boreal forests as an example. Ecol Bull 49: 11–41. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20113262.

Sikström U, Hjelm K, Holt Hanssen K, Saksa T, Wallertz K (2020) Influence of mechanical site preparation on regeneration success of planted conifers in clearcuts in Fennoscandia – a review. Silva Fenn 54, article id 10172. https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.10172.

Simonsen R (2013) Optimal regeneration method – planting vs. natural regeneration of Scots pine in northern Sweden. Silva Fenn 47, article id 928. https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.928.

Skre O, Wielgolaski FE, Moe B (1998) Biomass and chemical composition of common forest plants in response to fire in western Norway. J Veg Sci 9: 501–510. https://doi.org/10.2307/3237265.

Strand M, Löfvenius MO, Bergsten U, Lundmark T, Rosvall O (2006) Height growth of planted conifer seedlings in relation to solar radiation and position in Scots pine shelterwood. For Ecol Manag 224: 258–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2005.12.038.

Sundkvist H (1994a) Extent and causes of mortality in Pinus sylvestris advance growth in northern Sweden following overstorey removal. Scand J For Res: 158–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/02827589409382826.

Sundkvist H (1994b) Initial growth of Pinus sylvestris advance reproduction following varying degrees of release. Scand J For Res 9: 360–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/02827589409382852.

The Swedish Forest Agency (2020) Proportion of regeneration method at the country level (%). Skogssyrelsen. https://pxweb.skogsstyrelsen.se/pxweb/sv/Skogsstyrelsens%20statistikdatabas/Skogsstyrelsens%20statistikdatabas__Atervaxternas%20kvalitet/. Accessed 26 September 2023.