Pendulous lichen colonization in small gap openings can enable a resource continuum for reindeer

Rikkonen T., Hallikainen V., Turunen M., Rautio P. (2025). Pendulous lichen colonization in small gap openings can enable a resource continuum for reindeer. Silva Fennica vol. 59 no. 3 article id 25021. https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.25021

Highlights

- Pendulous lichens successfully colonized seedlings in small gap openings

- Colonization was most successful in the smallest gaps (d = 20 m) and near gap edges

- Higher seedling density and greater seedling height increased the probability of lichen colonization

- Pendulous lichens on adjacent mature trees promoted colonization within gaps

- Small gap cutting can facilitate the coexistence of commercial forestry and reindeer husbandry.

Abstract

In northern Finland, continuous cover forestry (CCF), has been introduced to better reconcile multiple land uses, including commercial forestry and reindeer husbandry. We studied how small gap cutting, a CCF method, can facilitate the colonization of pendulous lichens (Alectoria sp., Bryoria sp., and Usnea sp.), a bottle-neck resource for reindeer (Rangifer tarandus tarandus), into harvested areas. To assess the potential for balancing between forestry and reindeer husbandry, we investigated the colonization success of pendulous lichen on seedlings within the gaps created ten years before onset of our study in a pine-dominated boreal forest in central Finnish Lapland. The study included three gap sizes (diameters 20, 40, and 80 m) in xeric and sub-xeric sites, arranged in six randomized blocks, with 18 replicates per each gap size. Additionally, we examined the influence of gaps on the abundance of pendulous lichens in mature trees in the surrounding forest. Our results indicate that pendulous lichens colonized the smallest gaps (d = 20 m) efficiently, while colonization success declined as gap size increased. Colonization was strongly associated with seedling density, as a higher number of seedlings within gaps increased the probability of lichen colonized seedlings. The highest colonization rates occurred near gap edges, with lower colonization in the center. Furthermore, seedling height positively influenced colonization, and the presence of pendulous lichens on adjacent mature trees enhanced seedling colonization within gaps. However, we also observed that gap edges significantly reduced the amount of pendulous lichens on mature trees.

Keywords

continuous cover forestry;

forestry;

uneven-aged forestry;

multiple use of forests;

reindeer husbandry;

land use conflicts;

small gap cutting

-

Rikkonen,

Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke), Ounasjoentie 6, FI-96200 Rovaniemi, Finland; Arctic Centre, University of Lapland, POB 122, FI-96101 Rovaniemi, Finland

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7352-5241

E-mail

taru.rikkonen@luke.fi

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7352-5241

E-mail

taru.rikkonen@luke.fi

-

Hallikainen,

Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke), Ounasjoentie 6, FI-96200 Rovaniemi, Finland

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5384-8265

E-mail

ext.ville.hallikainen@luke.fi

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5384-8265

E-mail

ext.ville.hallikainen@luke.fi

-

Turunen,

Arctic Centre, University of Lapland, POB 122, FI-96101 Rovaniemi, Finland

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3425-6472

E-mail

minna.turunen@ulapland.fi

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3425-6472

E-mail

minna.turunen@ulapland.fi

-

Rautio,

Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke), Ounasjoentie 6, FI-96200 Rovaniemi, Finland

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0559-7531

E-mail

pasi.rautio@luke.fi

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0559-7531

E-mail

pasi.rautio@luke.fi

Received 5 June 2025 Accepted 10 December 2025 Published 22 December 2025

Views 20275

Available at https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.25021 | Download PDF

Supplementary Files

1 Introduction

In Northern Finland, forestry and reindeer herding have competed for the same space for over a century, with periodic conflicts from their overlapping resource use. The primary cause of these disputes is that both land use practices rely partly on the same forest resources, and forestry activities reduce the availability of grazing land of reindeer (Rangifer tarandus tarandus) (Turunen et al. 2020). The need for improved forest management practices that reconcile multiple land uses is becoming increasingly urgent, especially now when emerging industries, such as energy production and tourism intensify land use competition.

The dispute between forestry and reindeer husbandry is partly attributed to forestry practices that degrade winter forage sources of reindeer, particularly pendulous lichen (Dettki and Esseen 1998; Kivinen et al. 2010; Kumpula et al. 2019). Pendulous lichens (genera Alectoria, Bryoria, and Usnea) are macrolichens with a hair- or beard-like growth form that predominantly colonize trees (Dettki and Esseen 1998; Kivinen et al. 2010; Lommi 2011; Kumpula et al. 2019). The impact of forestry on pendulous lichens is problematic because these lichens serve as a bottle-neck resource for reindeer during late winter, when deep snow prevent access to ground vegetation (Helle and Saastamoinen 1979; Kumpula et al. 2020). Forest rejuvenation following timber harvesting negatively affects pendulous lichens, as they typically thrive in old-growth forests (Esseen et al. 1996; Kuusinen and Siitonen 1998; Peura et al. 2018; Nirhamo et al. 2023). Similar patterns of lichen decline due to forest rejuvenation have also been observed in North America (Stevenson and Coxson 2003).

Pendulous lichens, like all lichens, are generally long-living, and slow-growing organisms (Nash 2008; Lohtander 2011). Their growth rates vary from a few millimeters to a centimeter per year and are influenced by environmental factors such as solar radiation and moisture availability. Even though lichens are one of the most resilient organisms, they are highly sensitive to disturbances due to their slow growth and dependence on suitable substrates (Esseen et al. 1996; Dettki and Esseen 1998). In addition to their role as a key winter forage for reindeer, pendulous lichens contribute to forest ecosystems by, for example, providing food, nesting material, and habitat for various animals (Carroll 1980; Hayward and Rosentreter 1994; Pettersson et al. 1995), contributing to nutrient cycles (Pike 1978), and enhancing species diversity (Lesica et al. 1991; Dettki and Esseen 1998; Miina et al. 2020).

The occurrence and availability of pendulous lichen habitat are influenced by forest age and tree species (Esseen et al. 1996; Nirhamo et al. 2023). These lichens are generally more abundant and diverse in old-growth forests compared to younger stands (Esseen et al. 1996), though other factors such as soil type, climate, microclimate, and forest type also play a role (Stevenson 1985; Dettki and Esseen 1998; Campbell and Coxson 2001; Jaakkola et al. 2006; Nash 2008; Rikkonen et al. 2023). Pendulous lichens occur most abundantly in old coniferous forests, particularly dominated by Norway spruce (Picea abies (L.) H. Karst.) (Esseen et al. 1996).

Lichens propagate either sexually or asexually, with most species utilizing both ways (Myllys 2011). Asexual propagation, usually occurring through wind-dispersed lichen fragments, is the dominant method for local dispersal (Stevenson 1985; Myllys 2011) and is critical for maintaining the lichen continuum. Effective dispersal distances typically range between 100 and 300 meters (Stevenson 1988; Dettki et al. 2000), though some lichen fragments can be found up to two kilometers from the source (Goward 2003). A windier environment may enhance particle detachment and facilitate lichen dispersal, including into open-cut areas. Therefore, the presence of lichen-rich stands and trees is crucial as acting as a source of lichen particles, and often the highest amounts of pendulous lichens are found on large trees (Coxson et al. 2003; Rikkonen et al. 2023).

Due to the slow growth rate of pendulous lichens, maintaining diverse lichen colonies is challenging in commercial forests that rely solely on even-aged forestry practices (Dettki and Esseen 1998). Pendulous lichens disappear immediately with the trees they grow on during harvesting, but also the remaining trees often support fewer lichens than they did prior to logging (Rytkönen et al. 2013). Furthermore, the recovery of pendulous lichens requires a longer time span than the rotation periods typically offered by even-aged forestry (Armleder and Stevenson 1994; Horstkotte et al. 2011).

To reconcile competing land use objectives, continuous cover forestry (CCF) has been introduced as an alternative to traditional even-aged management. CCF combines various silvicultural methods with the aim of enhancing forest multifunctionality compared to traditional even-aged managed forests (Pukkala et al. 2012; Valkonen 2020; Brunner et al. 2025). In managed forests, CCF may provide a viable means of sustaining pendulous lichens and thereby support the coexistence of commercial forestry with reindeer husbandry (Kumpula et al. 2019; Rikkonen et al. 2023). Unlike large-scale clear-cutting, gap cutting – one of the CCF methods – retains parts of the forest stand untouched, helping preserve additional ecosystem functions. Another CCF method, selection cutting, aims to remove large (and old) trees that are also preferred by pendulous lichens. Thus, small gap cuttings may be more favorable for maintaining pendulous lichen populations than selection cutting.

The effects of different CCF methods on pendulous lichens in not yet fully understood, despite previous research conducted in North America (Rominger et al. 1994; Coxson et al. 2003; Stevenson and Coxson 2007; Stone et al. 2008; Boudreault et al. 2013), Sweden (Esseen et al. 1996; Ackemo 2018; Esseen and Coxson 2024), and Finland (Rikkonen et al. 2023). The colonization of pendulous lichens on seedlings, in particular, has received limited attention, and is not well studied. It is known that gap cutting influences pendulous lichen abundance through both direct and indirect ways. The direct removal of trees results in immediate loss of lichens and suitable growing substrates, while the creation of canopy gaps alters microclimatic conditions, like exposure to sunlight, rain, and wind, potentially affecting lichen growth and survival (Esseen and Renhorn 1998; Coxson et al. 2003; Esseen and Coxson 2024). However, gaps also facilitate new tree generation, thereby providing new growing substrates for lichens over time (Stevenson and Coxson 2007). The edge effects of the canopy gaps can also influence the amount and length of pendulous lichens up to 50 meters into the forest (Esseen and Renhorn 1998).

However, previous studies have shown that some pendulous lichen species, like genus Bryoria, may benefit from partial cuttings due to increased light exposure, until the new tree generation begins to shelter the canopy (Rominger et al. 1994; Coxson et al. 2003; Stevenson and Coxson 2007; Stone et al. 2008). Furthermore, gaps can influence species composition by altering the relative abundance of shade-tolerant and shade-intolerant species. Even though some lichen species benefit from increased exposure on residual trees at the gap edges, overall lichen biomass may remain unchanged or even decline following CCF interventions. This is likely due to certain lichen species exhibiting reduced abundance at gap edges after harvesting (Esseen and Renhorn 1998; Stevenson and Coxson 2003; Stone et al. 2008; Boudreault et al. 2013).

In CCF, the time between cuttings is typically shorter than in even-aged forestry, which may limit the time available for lichens to establish and accumulate biomass on trees. However, silvicultural treatments can increase lichen litterfall, potentially facilitating colonization in the new tree generation (Stone et al. 2008). A heavy tree removal, however, decreases the lichen abundance for many years. Given their slow growth rates and reliance on lichen fragments for propagation, early attachment to tree seedlings is essential for maximizing lichen biomass, already in younger trees. While the colonization of pendulous lichens on small saplings and seedlings remains relatively understudied, Ackemo (2018) observed that they are capable of establishing on seedlings withing gaps.

Partial cuttings, which enhance the exposure of residual trees while keeping basal area removal low and retaining large and old trees, have been shown to better maintain reindeer and caribou forage compared to other forestry methods (Coxson et al. 2003; Stevenson and Coxson 2007; Rikkonen et al. 2023). Among the two most common CCF methods – small gap cutting and selection cutting – small gap cutting has been identified as a more effective approach for maintaining pendulous lichens in managed forests. This is because small gap cutting keeps patches of forest unmanaged for a longer time, thereby providing more time for pendulous lichen to establish and grow (Rikkonen et al. 2023).

In this study, we aim to examine how small gap cuttings, as a CCF method, affect the abundance of pendulous lichens ten years after cutting in a pine-dominated forest in South-Lapland, Finland. Specifically, we investigate how pendulous lichen propagates onto pine seedlings within gaps of varying sizes (diameters 20 m, 40 m, and 80 m) and whether the lichens can effectively colonize also the centers of these gaps. In this study, we refer to all trees remaining in the gaps as seedlings, even though some may be relatively old (up to 79 years; Table 1) but remain relatively short (median height of 108 cm). We also assess how the edges of the gaps influence pendulous lichen propagation within the gaps and the abundance of pendulous lichen on mature trees located at the gap edges and within the surrounding forest. Through this investigation, we aim to determine whether small gap cutting can be effectively used to manage pendulous lichen in multipurpose forests where both commercial forestry and reindeer herding are practiced.

Based on previous studies, we hypothesize that pendulous lichens can propagate also into the centers of the gaps, but that the propagation will be lower in the center and in larger gaps compared to the edges and smaller gaps. We also hypothesize that taller seedlings within the gaps will support more pendulous lichens than shorter seedlings. Additionally, due to edge effects, we expect that mature trees at the edges of the gaps will host less pendulous lichens compared to mature trees within the forest interior.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Study area

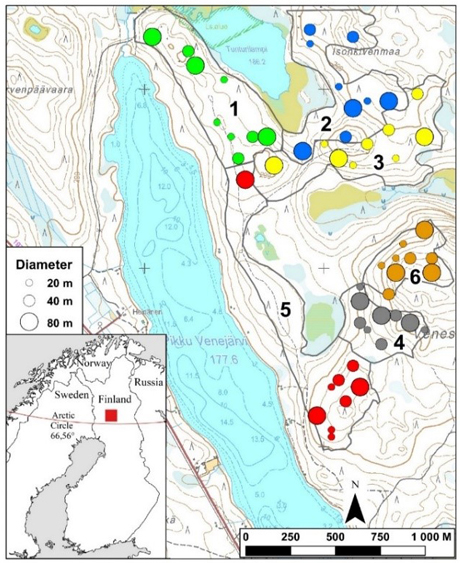

The study area is located in central Finnish Lapland, on Veneselkä hill in Rovaniemi, approximately 70 km north from the Arctic circle (Fig. 1). The area belongs to the subarctic climate zone, which is characterized by relatively cold and harsh conditions, with cold winters and short, cool to warm summers (Köppen 1936; Peel et al. 2007). The long-term mean temperature recorded at Rovaniemi Airport (located relatively close to the study site) is –10.4 °C in January and 15.7 °C in July, with an annual mean temperature of 1.5 °C (Jokinen et al. 2021). Annual precipitation is 633 mm, and the maximum snow depth, typically measured on March 15, is approximately 77 cm.

Fig. 1. Location of the study site in Veneselkä hill in Rovaniemi, with gap cuttings randomized into six blocks (indicated by different colors). Figure modified from Hallikainen et al. (2019).

The study site is part of the Northern Boreal vegetation zone (Kalela 1961) and its sub-zone “Southern Lapland (“Peräpohjola”) which is characterized by coniferous forests dominated by Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) and Norway spruce. The area consists of a mosaic of sub-xeric Empetrum-Vaccinium (EVT) and xeric Myrtillus-Calluna-Cladonia (MCClT) site types (Cajander 1926). Veneselkä area represents a typical multiple-use forest, where forestry, reindeer herding, and recreation are practiced. The area also contains several holiday homes.

The study area covers approximately 3 km2 and is located within an experimental CCF stand in a relatively heterogenous, Scots pine-dominated forest. It consists of large mature trees and naturally regenerated small gap cutting patches, which were cut in March 2010 (Hallikainen et al. 2019; Miettinen et al. 2024).

2.2 Sampling design and data preparation

The study area was divided into six blocks (Fig. 1), each with an average size of 30 ha (range 15–40 ha) (Hallikainen et al. 2019; Miettinen et al. 2024). The blocks were selected to be as homogenous as possible in terms of site type, stand age, and stand structure (i.e., variation in tree size). A rectangular grid of points, spaced at 40 m intervals, was established within each block. Nine points on the grid were randomly selected within each block. Gaps of variable sizes were randomly assigned to these random points, with three replicates per block, and gaps of varying sizes were randomly assigned to these points, with three replicates per block.

The gap cuttings were conducted in March 2010. The gaps were circular, with diameters of 20 m, 40 m, or 80 m, corresponding to areas of 0.03 ha, 0.13 ha, and 0.5 ha, respectively. Each block contained three gaps of each size, resulting in a total of 54 gaps (18 per size class). A buffer of uncut forest, with a minimum width of 30 m, was maintained between the gaps and around the blocks. An additional 30 m buffer was preserved between individual gaps. If a selected grid point did not meet these spatial criteria, it was discarded and replaced randomly. Stand characteristics of the sections were recorded before the cuttings using five circular sample plots: one in the middle (radius = 9.77 m), and four at the cardinal directions (radius = 5.64 m) positioned six meters away from the edge of the gap.

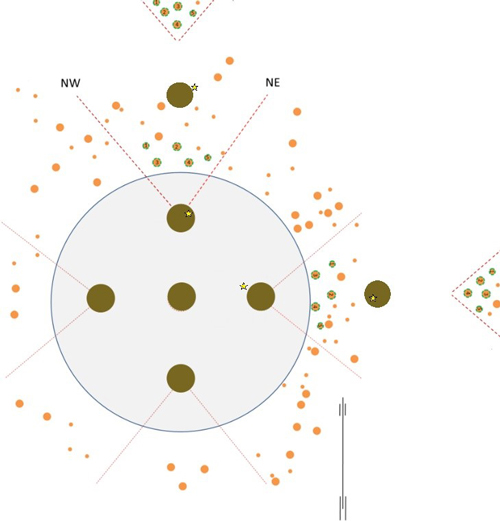

In the summer of 2010, nine circular sample plots (radius = 1.26 m = 5 m2) were established within each gap. One plot was placed at the center of the gap, and one at the forest edge in all four cardinal directions (N, E, S, W). In addition, a control plot was positioned 12 meters from the edge into the forest buffer zone in each four cardinal direction (Fig. 2), resulting in a total of 486 sample plots. Site preparation, including patch scarification, was conducted in all gaps in early summer 2010. All pre-existing seedlings within the circular sample plots were removed.

Fig. 2. Example of the sampling design with a gap (d = 20 m). Five circular regeneration plots in brown are shown within the gap, and two additional plots outside the gap on the northern and eastern sides represent the four control plots positioned in all four cardinal directions. The orange dots represent trees, and the dots with a green outline represent the dominant trees from which pendulous lichen abundance were assessed. The dots further away on the northern and eastern sides represent the sample trees within the forest in all four cardinal directions (~15 m from the outer border of the control plots). Figure modified from Hallikainen et al. 2019.

During the summers of 2020 and 2021, the number and height of naturally regenerated seedlings (d1.3 < 4.5 cm) within the circular sample plots (Table 1) and the number of pendulous lichen-colonized Scots pine seedlings were recorded. Additionally, the presence of pendulous lichen on the tallest seedling within five meters from the center of each circular sample plot (hence the tallest seedling could also be located outside the sample plot) was recorded. An example of a pendulous lichen-colonized seedling is shown in Fig. 3. A tree was categorized as a seedling if it was under 4.5 cm thick on the breast height (d1.3).

| Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the covariates and the responses tested in the models 1–3. In addition to these, the categorical variables gap diameter and direction of a circular sample plot were tested in the models. Pendulous lichen category comes from the pendulous lichen assessed from five nearest dominant trees in each cardinal direction within each gap (following the methods described by Kumpula et al. (2006). Abbreviations used: Qu. = quartile, d1.3 = diameter at breast height (1.3 m). | ||||||

| Min. | 1.Qu. | Median | Mean | 3.Qu. | Max. | |

| At sample plot level | ||||||

| Number of seedlings with pendulous lichens on circular sample plot (response) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.86 | 1.00 | 11.00 |

| Number of all seedlings on plot (only plots recruited by seedlings) | 1.00 | 9.00 | 17.00 | 21.40 | 29.75 | 102.00 |

| Number of Scots pine seedlings on plot (only plots recruited by seedlings) | 0.00 | 8.00 | 14.50 | 17.21 | 24.00 | 65.00 |

| Height of Scots pine seedlings on plot, cm | 2.00 | 12.00 | 20.00 | 26.80 | 36.00 | 139.00 |

| Age of Scots pine seedlings on plot, years | 2.00 | 5.00 | 6.00 | 6.05 | 7.00 | 14.00 |

| Height of all seedlings on plot, cm | 2.00 | 11.00 | 17.83 | 22.70 | 30.00 | 91.00 |

| Height of longest Scots pine seedling, cm | 7.00 | 78.00 | 108.00 | 121.60 | 150.00 | 440.00 |

| Age of longest Scots pine seedling, years | 4.00 | 10.00 | 15.00 | 19.86 | 26.00 | 79.00 |

| At gap level, gap edge parameters | ||||||

| Basal area, m2 ha–1 | 0.57 | 13.79 | 17.68 | 18.13 | 22.46 | 35.83 |

| Number of tree stems ha–1 | 50.00 | 400.00 | 625.00 | 644.10 | 850.00 | 1450.00 |

| Total volume of tree trunks, m3 ha–1 | 3.31 | 112.04 | 144.51 | 149.15 | 185.54 | 327.68 |

| Mean diameter (d1.3) of trees, cm | 8.89 | 14.11 | 17.17 | 17.90 | 20.19 | 31.73 |

| Mean height of trees, m | 9.38 | 12.38 | 13.45 | 13.84 | 15.08 | 19.60 |

| Mean of pendulous lichen category (categories 0–3, 10 trees classified) | 0.70 | 1.10 | 1.30 | 1.29 | 1.40 | 2.00 |

Fig. 3. Example of a Scots pine seedling with pendulous lichen (and some bark) attached.

The amount of pendulous lichen was also assessed on the five nearest dominant trees in each four cardinal direction within each gap, and five dominant trees within the forest buffer zones, positioned 15 meters from the control plot in each cardinal direction (Fig. 2), following the methods described by Kumpula et al. (2006). Lichen abundance was estimated from the branches and the trunk of each tree in three height zones: <2 m, 2–5 m, and >5 m. The following abundance classes were used to quantify pendulous lichen coverage: 0= no pendulous lichens; 1 = short pendulous lichens or sheaths of pendulous lichens are abundant, with a maximum length of one centimeter; 2 = pendulous lichens are observed almost entirely in long-growing form or in sheaths, with a length of approximately two to five centimeters; 3 = long or longish pendulous lichens, or sheaths of lichen, are growing generally or throughout the tree (over five centimeters, often exceeding ten centimeters) (Kumpula et al. 2006; Rikkonen et al. 2023; Supplementary file S1). The lichen categories used in the modelling were calculated as the mean of ten dominant trees at the forest edge and inside the forest in each cardinal directions. Descriptive data are provided in Table 1.

2.3 Statistical modelling

Four models were constructed for the statistical modelling: a negative binomial model for the number of pendulous lichen-colonized Scots pine seedlings (Model 1), a binomial model for the presence of pendulous lichens on the longest single seedlings nearest to the circular sample plots (Model 2), a linear model for the pendulous lichen category within the forest interior and at the gap edge (Model 3), and a model to test the possible differences in forest edge characteristics between the cardinal directions (Model 4), and since this model belongs to the data description, it will be described in section 2.3.4.

In the models, where model predictions were computed and plotted, the R-packages ggeffects (Lüdecke 2018) and ggplot2 (Wickham 2016) were used. Mixed models were used due to the hierarchical structure of the data. The hierarchy was as follows, from highest to the lowest: 1) block, 2) gap nested within block, and 3) circular sample plot (Models 1 and 3) or seedling (Model 2) nested within gap.

The independent variables tested, along with their distributions, are presented in Table 1. Given the large number of potential independent fixed variables, model building could not proceed by starting with a full model, as suggested by Zuur et al. (2009). Instead, a pre-selection process was used, including variables with statistically significant p-values that contributed to the response. After pre-selection, candidate variables and their potential two-way interactions were tested simultaneously through several include-drop stages.

The count model (Model 1) was considered the primary model, and all selected variables or terms (interactions) in this model were significant at 5% risk levels. In the pendulous lichen presence model (Model 2), variables that were significant in Model 1 were included, provided they were near the significance level and could be ecologically justified for the propagation of pendulous lichen. When computing predictions for a given predictor, other predictors were set to their mean values or levels.

Potential multicollinearity among the main-effect models between the selected variables were tested using performance R-package (Lüdecke et al. 2021). The Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) value of 10 (Hair et al. 1998) or as low as 5 or 3 (Hair et al. 2021) is typically considered the upper limit to avoid multicollinearity. In our case the VIF values for all the main effects were below 2.

General or generalized linear mixed models are known to sometimes underestimate the mean. To address this, a ratio estimator (ratio of observed to predicted mean, Snowdon 1991) was computed.

2.3.1 Model for the number of pendulous lichen-colonized seedlings (Model 1)

A negative binomial model (Model 1) was developed to describe the number of pendulous lichen-colonized Scots pine seedlings on 5 m2 circular sample plots. The negative binomial model can be described as:

![]()

![]()

, where yijk is the response variable of the counts (pine seedlings with pendulous lichens) in a sample plot (k), nested within the gaps (j), nested within the blocks (i). πijk represents (conditional) expected value and θ represents estimated clumping parameter (theta, see Eq. 3), log(πijk) denotes log-link function and f(Xijk,β) describes the linear function, i.e. fixed predictors that have been measured from the levels i, j or k, β representing parameter estimates. Furthermore, μi denotes block variance and μij denotes gap variance.

The models were estimated using R-package glmmTMB (Brooks et al. 2017) using NB2 parametrization. The variance function in NB2-parametrization was defined as:

, where π denotes estimated expected value and θ estimated clumping parameter. The potential presence of extra-zero values in the response variable was tested using R-package DHARMa (Hartig 2021).

2.3.2 Model for the presence of pendulous lichen on the longest seedling (Model 2)

A binomial model (Model 2) was constructed to describe the presence of pendulous lichen on the longest single seedling within a 5-meter radius from the center of the circular sample plot. The presence of pendulous lichen was modelled using a binomial (Bernoulli) distribution assumption. The model was estimated using the R-package, glmmTMB (Brooks et al. 2017). The model can be described as:

![]()

where y represents the probability of the event, i.e. the presence of pendulous lichen on a seedling. The term binomial(n,π) denotes a binomial distribution with parameters n (describing the binomial sample size, in our case the number of seedlings) and π (describing the probability of event), the presence of pendulous lichens on a seedling. The term  is the logit-link function, and f(Xijk,β) describes the linear function. The subscript notations denote: i = block, j = gap and k = circular sample plot (in Model 1). In Model 2 subscript k refers to the longest seedling.

is the logit-link function, and f(Xijk,β) describes the linear function. The subscript notations denote: i = block, j = gap and k = circular sample plot (in Model 1). In Model 2 subscript k refers to the longest seedling.

The most relevant independent fixed variables in the models included the number of seedlings, gap diameter (20, 40 and 80 m), and the direction from the gap center. The directions were classified as gap center (reference category), north, east, south, and west. The number of seedlings was treated as a fixed variable because the strength and linearity of its effect provided insights into the ecological process driving seedling density on the spread and colonization of pendulous lichens on the seedlings.

2.3.3 Model testing differences in forest characteristics across different directions (Model 3)

A linear mixed model (Model 3) was constructed to examine differences in the amount of pendulous lichen on mature trees between the forest edge and the forest interior. In this model, block and gap nested within block were treated as random effect variables, while location (forest edge or forest interior) was the sole fixed variable. The response variable was the pendulous lichen category. The model was computed using R-package nlme (Venables and Ripley 2002).

2.3.4 Data description

The distributions of the variables, characterized by key distribution parameters (Table 1), indicated that the mean number of pendulous lichen-colonized seedlings was 0.86 per circular sample plot, while the mean number of Scots pine seedlings was 21.4 per plot. The number of pendulous lichen-colonized seedlings increased gradually with the increasing number of seedlings, the 3rd quarter being 1 reaching its maximum, 11 seedlings in the end of the distribution.

An average Scots pine seedling on a circular sample plot was approximately 6 years old and 27 cm tall. The mean height of all seedlings in the circular sample plot was slightly lower, about 23 cm. The age of all seedlings could not be reported, as only the ages of Scots pines were measured.

Among the longest Scots pine seedlings within a 5-meter radius from the center of a circular sample plot, 47% were colonized by pendulous lichen. This Bernoulli-distributed variable served as the response variable in Model 2. The average height of the longest Scots pine seedling was 122 cm, with an average age of 20 years. However, the range was considerable: seedling age varied from 4 to 79 years, and height ranged from 7 cm to 440 cm.

Forest characteristics at the forest edges of the gaps were tested according to the cardinal directions, with the gap center representing the average of all other directions (Suppl. file S2). Due to the hierarchical structure of the data, a linear mixed effects model was applied for the tests. In this model, block was the sole random variable, while direction was treated as the fixed variable, with forest edge characteristics as the response variables. The model was computed using R-package nlme (Venables and Ripley 2002).

The variability between the forest edge and forest interior were considerable (Suppl. file S2). The amplitude of the quarters suggested that the forests were predominantly mature, but the minimum and maximum values showed substantial deviations from the median or mean (Table 1). Differences in forest characteristics between the cardinal directions were significant for model interpretation. The most notable differences were in the number of stems and the basal area of the forests, with the differences in the number of stems being the only significant difference at 5% risk level (Suppl. file S2). The Suppl. file S2 suggests that forests were sparsest on the southern side of the gaps and densest on the northern side of the gaps.

3 Results

3.1 Number of pendulous lichen-colonized seedlings (Model 1)

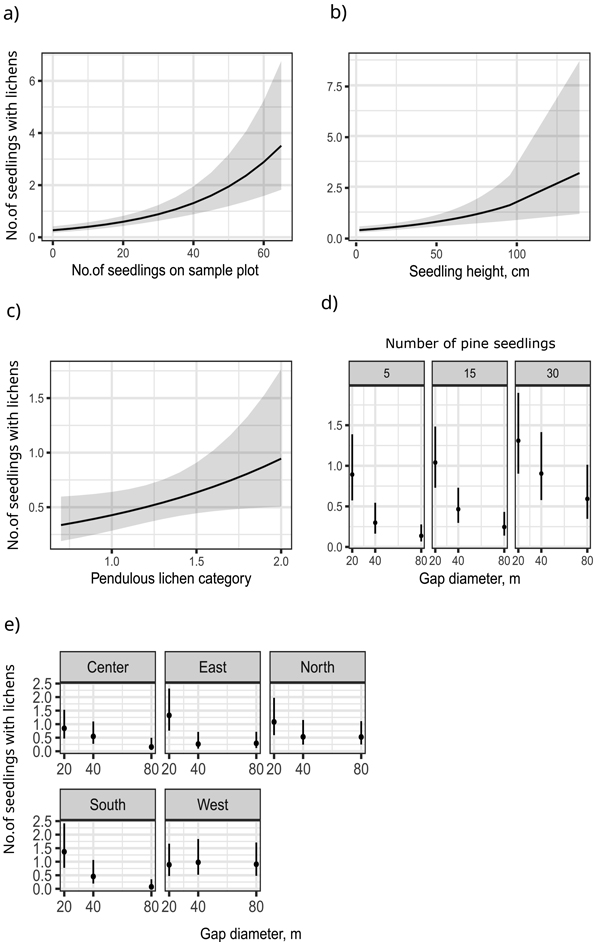

The primary effect of seedling density suggested that pendulous lichen colonization on seedlings increased with higher number of seedlings, but the relation was non-linear. The proportion of colonized seedlings relative to the total number of seedlings increased with higher number of seedlings (Fig. 4a). Model predictions for the number of pendulous lichen-colonized seedlings within the 5 m2 circular sample plot suggested that when approximately 35 seedlings were present, one of them was colonized by pendulous lichens.

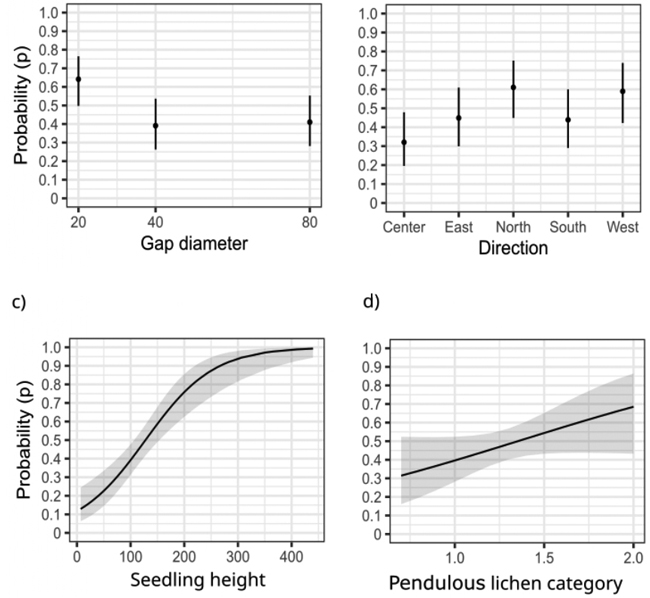

Fig. 4. Model 1 predictions and 95% confidence intervals for the number of pendulous lichen-colonized seedlings in the function of the following explanatory variables: number of Scots pine seedlings on a circular sample plot (a), Scots pine seedling height (b), pendulous lichen category at the forest edge (c), the interaction of gap size and number of seedlings at given values of 5, 15 and 30 seedlings in a sample plot (d), and interaction of gap size and direction (e). Pendulous lichen category comes from the pendulous lichen assessed from five nearest dominant trees in each cardinal direction within each gap (following the methods described by Kumpula et al. (2006).

Seedling height within a circular sample plot positively influenced the number of pendulous lichen-colonized seedlings (Fig. 4b). Additionally, the abundance of pendulous lichens on mature trees at the gap edge and within the forest interior (as reflected by the mean pendulous lichen category in Table 2) influenced the proportion of pendulous lichen-colonized seedlings in the sample plots (Fig 4c, Table 2).

| Table 2. Generalized linear mixed model to explain the number of pendulous lichen-colonized seedlings using a negative binomial (Model 1) (NB2-parametrization) distribution assumption. VIF denotes the variance inflation factor values for the main effects of the predictors. The marginal model R2 = 52.3%. | |||||

| Variable | Estimate | Std.error | z-/chi-value | p | VIF |

| Fixed effects | |||||

| (Intercept) | –1.904 | 0.655 | –2.909 | 0.004 | |

| Gap diameter, m (20 m being ref. category) | 12.961 | 0.002 | 1.23 | ||

| 40 m | –0.936 | 0.514 | –1.820 | 0.069 | |

| 80 m | –2.430 | 0.695 | –3.494 | <0.001 | |

| Direction (Center being ref. category) | 2.668 | 0.615 | 1.45 | ||

| North | 0.246 | 0.392 | 0.627 | 0.531 | |

| East | 0.447 | 0.374 | 1.196 | 0.232 | |

| South | 0.479 | 0.383 | 1.251 | 0.211 | |

| West | 0.045 | 0.396 | 0.114 | 0.909 | |

| No of seedlings on circular sample plot (5 m2) | 0.015 | 0.009 | 1.717 | 0.086 | 1.07 |

| Height of seedlings, cm | 0.016 | 0.005 | 3.532 | <0.001 | 1.36 |

| Mean of pendulous lichen category (categories 0–3) | 0.794 | 0.393 | 2.022 | 0.043 | 1.07 |

| Gap diameter * No of seedlings on plot | 8.592 | 0.014 | |||

| 40 m | 0.029 | 0.015 | 1.877 | 0.061 | |

| 80 m | 0.043 | 0.016 | 2.744 | 0.006 | |

| Gap diameter * Direction | 18.448 | 0.018 | |||

| 40 m * North | –0.276 | 0.615 | –0.449 | 0.654 | |

| 80 m * North | 0.959 | 0.754 | 1.271 | 0.204 | |

| 40 m * East | –1.173 | 0.674 | –1.741 | 0.082 | |

| 80 m * East | 0.172 | 0.781 | 0.221 | 0.825 | |

| 40 m * South | –0.666 | 0.632 | –1.053 | 0.292 | |

| 80 m * South | –1.244 | 1.015 | –1.225 | 0.220 | |

| 40 m * West | 0.532 | 0.583 | 0.913 | 0.361 | |

| 80 m * West | 1.701 | 0.730 | 2.331 | 0.020 | |

| Random effects | Variance | ||||

| Block | 0.085 | ||||

| Gap nested within Block | <0.001 | ||||

| Theta (NB2 parameter) | 2.720 | ||||

The interaction between gap diameter and seedling density on a sample plot suggested that when seedling density was high, the effect of gap size on lichen colonization was less pronounced. Differences in colonization between gap sizes diminished when seedling density increased within the sample plot (Fig. 4d).

An increase in gap diameter reduced the number of pendulous lichen-colonized seedlings (Fig. 4e). This effect was evident in all cardinal directions except west, where gap diameter had no significant influence on seedling colonization. Notably, smallest gaps with a diameter of 20 meters facilitated pendulous lichen colonization more effectively than larger gaps.

3.2 Pendulous lichen colonization on the tallest seedling (Model 2).

The probability of colonization on the tallest seedling was higher in the smallest gaps (20 m diameter) compared to the larger gaps (40 m and 80 m) (Fig. 5a). The effect of gap size was statistically significant (Table 3), although the magnitude of the effect was relatively modest.

Fig. 5. Model 2 predictions and 95% confidence intervals for pendulous lichen colonization on the tallest seedlings: effect of gap diameter (m) (a), direction (b), height (cm) of the tallest seedling (c), and pendulous lichen category (mean of 10 trees) (d). Pendulous lichen category comes from the pendulous lichen assessed from five nearest dominant trees in each cardinal direction within each gap (following the methods described by Kumpula et al. 2006).

Direction, which clearly affected the number of pendulous lichen-colonized seedlings depending on gap size, had only a minor effect on the probability of colonization of the tallest seedling (Table 3, Fig. 5b). However, seedlings located near the forest edge tended to have a higher probability of pendulous lichen colonization compared to those growing at the center of the gap.

| Table 3. Generalized linear mixed-effects based on a binomial (Bernoulli) distribution for the presence of pendulous lichens on the tallest seedling (Model 2). VIF denotes the variance inflation factor values for the main effects of the predictors. The marginal model R2 = 33.6%. The area under the ROC-curve = 0.745 (marginal model). | |||||

| Variable | Estimate | Std.error | z-/chi-value | p | VIF |

| Fixed effects | |||||

| Intercept | –3.563 | 1.034 | –3.447 | 0.001 | |

| Gap diameter, m (20 m being ref. category) | 7.033 | 0.030 | 1.09 | ||

| 40 m | –1.014 | 0.423 | –2.399 | 0.016 | |

| 80 m | –0.934 | 0.423 | –2.209 | 0.027 | |

| Direction (Center being ref. category) | 8.931 | 0.063 | 1.06 | ||

| North | 1.190 | 0.457 | 2.605 | 0.009 | |

| East | 0.543 | 0.453 | 1.198 | 0.231 | |

| South | 0.504 | 0.451 | 1.117 | 0.264 | |

| West | 1.104 | 0.467 | 2.366 | 0.018 | |

| Mean of pendulous lichen category (categories 0–3) | 1.186 | 0.700 | 1.693 | 0.090 | 1.03 |

| Height of the longest seedling, cm | 0.016 | 0.003 | 4.791 | < 0.001 | 1.11 |

| Random effects | Variance | ||||

| Block | <0.001 | ||||

| Gap nested within Block | 0.428 | ||||

Among the tallest seedlings in the circular sample plots or their immediate vicinity, 47% were colonized by pendulous lichens. The probability of pendulous lichen colonization increased significantly with the height of the tallest seedling (Table 3, Fig. 5c). When a seedling reached a height of 3–4 meters, the probability of finding pendulous lichen on it approached 100%.

The increasing abundance of pendulous lichen in the mature forest edge was associated with higher colonization rates on the tallest seedlings based on point estimates (Fig. 5d), although the main effect was not statistically significant (Table 3).

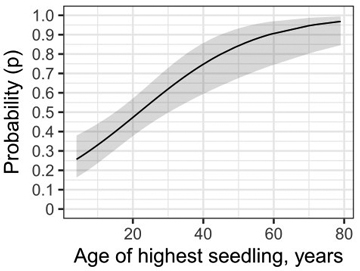

As an alternative model, seedling age was used instead of seedling height. Model predictions indicate that the colonization probability would exceed 80% when a seedling is at least 45 years old (Fig. 6). The effect of seedling age was highly significant (p < 0.001).

Fig. 6. Model 2 (alternative model) predictions and 95% confidence intervals for pendulous lichen colonization on the tallest seedlings when seedling height was replaced with seedling age.

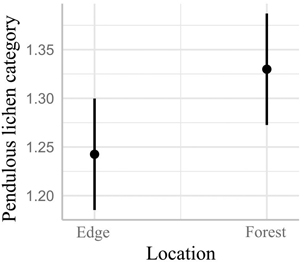

3.3 Differences in pendulous lichen abundance inside the forest and next to the gap edge (Model 3)

The linear mixed model for the abundance of pendulous lichen on mature trees revealed significantly higher pendulous lichen inside coverage inside the forest compared to the forest edge (Fig. 7, t = 3.024, df = 371, p = 0.003).

Fig. 7. Model 3 predictions and 95% confidence intervals for the abundance of pendulous lichens, as indicated by the pendulous lichen category, in the forest edge and interior.

3.4 Model performance and fit

The negative binomial count model provided a good fit to the data. The observed mean number of pendulous lichen-colonized seedlings was 0.86, while the predicted mean was 0.84. The minimum values were 0vs. 0.3, and the maximum values were 11.00 vs. 11.50, respectively. The simulated distribution fitted the observed count data moderately well, slightly underestimating the zero values and largest counts, while overestimating the seedling density (1 seedling per circular sample plot) (Suppl. file S3). The coefficient of determination for the marginal model was approximately 54%.

The test for the excessive number of zeroes in the negative binomial distribution suggested that the distribution fit the data adequately without the need for zero-inflation modeling. The ratio of observed to simulated zeros was 1.057, with a corresponding p-value of 0.296, indicating no significant difference between the observed and expected zeros.

The classification performance of the binomial marginal model (Model 2) for predicting pendulous lichen colonization on a single seedling was 74.5% (area under the ROC-curve). When seedling height was replaced by seedling age, the classification performance slightly decreased to (72.6%).

4 Discussion

Our results clearly show that ten years after cutting, pendulous lichens successfully colonized Scots pine seedlings in small gap openings in a coniferous boreal forest. These lichens were able to establish themselves not only in small continuous cover gaps, but also in larger openings, extending up to at least 80 meters in diameter. These findings suggest that seedling colonization is strongly influenced by the number of established seedlings within the gap; as the density of seedlings increases, so does the number of pendulous lichen-colonized seedlings. However, this relationship was not linear, suggesting that the microclimatic conditions created by seedlings positively influence lichen colonization. Consequently, higher seedling density intensifies the colonization of pendulous lichens.

The results also suggest that pendulous lichens face greater challenges in propagation into larger gaps. This is consistent with previous findings that the effective propagation distance of pendulous lichens is relatively short (Dettki et al. 2000; Stevenson and Coxson 2003). Nevertheless, colonization was observed even in the largest gaps (80 m diameter). The effect of gaps size varied depending on the direction and the number of seedlings within the circular sample plots. However, in general, the smallest gaps (20 m in diameter) exhibited the highest colonization rates.

Moreover, seedling height increased the probability of pendulous lichen colonization. We measured lichen abundance on the tallest seedlings and found lichen on nearly half of them. When seedling height exceeded two meters, the probability of lichen colonization was approximately 80%, and it was almost certain if the height exceeded three meters. This process, however, is slow; half of the seedlings had pendulous lichens on them only when they were over 20 years old. This implies that taller seedlings have had more time to catch and support the growth of pendulous lichens, while also providing a larger substrate for colonization. Our findings highlight the importance of preserving existing seedlings during small gap cuttings, as the tallest seedlings may have been located outside the sample plots and thus remained uncut. Ensuring that trees capture lichen fragments early in their development could help establish a sufficient amount of lichen while the trees are still relatively young.

These observations, showing that pendulous lichen colonization intensifies with seedling density and seedling height, contrasts with the findings of (Miettinen et al. 2024), who observed that although seedling density was higher in smaller gaps (20 m) than in larger ones (40 or 80 m), seedling growth was weaker in the 20 m gaps. Miettinen et al. (2024) concluded that the optimal gap size for Scots pine regeneration and growth is 40 m or more. Thus, there appears to be a conflict between the optimal gap size for pendulous lichen colonization and early seedling growth. Interestingly, our results indicate that when seedling density was high, gap size had less influence on pendulous lichen colonization. This suggests that creating favorable conditions for seedling regeneration can mitigate the negative effects of larger gaps on lichen colonization while simultaneously supporting seedling growth.

Usually, pendulous lichens prefer old trees, which provide sufficient time for lichen to attach and have bark suitable for lichen (Lommi 2011). However, in this study, we observed, that aided by wind, lichen particles can also colonize even the smallest seedlings.

It is important to note that patch scarification was conducted at our study site, which promotes seedling establishment and growth (Miettinen et al. 2024). Without this, seedling density – and consequently the abundance of pendulous lichens – would likely have been lower. Therefore, any actions that enhance seedling establishment and growth are likely to promote pendulous lichen colonization. However, over time, pendulous lichens are likely to colonize most trees naturally.

Additionally, we found that colonization was most effective near the gap edges and weakest at the center, consistent with the observations that lichen propagation is limited (Dettki et al. 2000). This indicates that the amount of lichen crumbs decreases with increasing distance from the edge towards the gap center. Furthermore, the presence of mature forest surrounding the gaps enhances lichen colonization, as it provides a source of lichen crumbs (Coxson et al. 2003).

There were also indications that wind and sunlight influence lichen abundance within the gaps. For instance, seedlings on the northern side of the gaps, which receive more sunlight exposure than the southern side, were more likely to host pendulous lichens. Previous studies have suggested that pendulous lichen can benefit from increased solar radiation or openness (Rominger et al. 1994; Stevenson and Coxson 2007; Stone et al. 2008; Esseen and Coxson 2024). However, the gaps also affect mature trees adjacent to the gaps; lichen abundance on mature trees at the gap edges was significantly lower than within the interior forest.

Even though gap cut forests could support more pendulous lichens than even-aged forestry (Rikkonen et al. 2023), gap cutting always creates new edge habitats, which reduce forest connectedness, one of the main factors driving the decline of pendulous lichens (Esseen and Renhorn 1998; Horstkotte et al. 2011). However, it is possible that, over time, lichen growth may be more effective in gap cut forests compared to uncut ones, and that the lichen lost during cuttings could be regained through this increased growth in subsequent years (Rominger et al. 1994).

It should also be noted that the maximum gap size allowed in CCF in Finland is 0.3 ha (60 m diameter) (Metsälaki 1996). The largest gaps in our study (0.5 ha) are therefore larger than the CCF limit but remain significantly smaller than the average clear-cut sizes in Finland (1.5 ha, (Mäntyranta 2014) or in Sweden (3.6 ha, Swedish Forest Agency 2024).

Although forestry is considered one of the greatest threats to lichens, reindeer grazing also influences lichens abundance and overall forest ecology (Stark et al. 2003; Akujärvi et al. 2014). Increasing land use and diminishing grazing areas are likely to increase grazing pressure on the remaining areas. The long-term effects of gap cutting on both reindeer and lichens remain partially unknown and could be complex. Gap cutting alters forest dynamics, which shift again as the seedlings mature. The changes in forest structure are likely to affect snow accumulation and distribution, which in turn could influence reindeer access to forage. Long-term shifts in stand structure may also alter the abundance and species composition of pendulous lichens (Armleder and Stevenson 1994).

Additionally, gap cutting requires operations over a larger area to achieve the same timber volume as even-aged forestry. More intensive forestry methods could potentially allow more areas to be completely excluded from forestry use.

It also must be acknowledged that gap cutting can be more costly than conventional even-aged forestry, and logging restrictions can result in economic losses due to reduced forest growth and timber yield. Since gap cutting may pose economic challenges for forest owners, attention should be given to forestry support and taxation, to ensure that methods beneficial to both society and ecosystem health are also financially viable for private forest owners. However, potential economic losses caused from gap cutting could be offset by increased biodiversity, enhanced carbon sequestration, and other ecosystem services (Miina et al. 2020). Methods like gap cutting and retention forestry are increasingly necessary to meet the changing public expectations, and biodiversity and climate targets.

5 Conclusion

This study demonstrates that maintaining pendulous lichen continuum in commercial forests can be supported through small gap cuttings, provided that the pre-existing seedlings are retained within the gaps, the gaps size remains at a maximum of 20 meters in diameter, and the gaps are situated adjacent to lichen-rich forests. Although the colonization process is slow, pendulous lichens can establish themselves within small gap cuttings if there is a sufficient amount of seedlings present. Therefore, small gap cutting represents a viable strategy for balancing forestry practices with reindeer husbandry. Overall, this research enhances our understanding of how pendulous lichens respond to small gap cuttings and provides new insights into their colonization on seedlings in boreal forests.

Acknowledgements

Tarmo Aalto, Pasi Aatsinki, Sami Hoppula, Jukka Lahti, Pekka Närhi and Merja Uutela carried out the seedling and stand parameter measurements. Pasi Aatsinki processed the data for statistical analysis. We would like to thank everyone involved in this study. Data is openly available in Zenodo: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17987696.

Author contributions

The experiment was designed by V. Hallikainen. Lichen inventory was planned by V. Hallikainen, P. Rautio and T. Rikkonen. Hallikainen performed the statistical analyses in consultation with the other authors. Rikkonen wrote the first draft, and all the authors edited the manuscript drafts.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

AI technologies (ChatGBT) were used to assist in transcribing the text. After using this service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Funding

Metsähallitus supported T. Rikkonen during the field inventory of pendulous lichen. This study was conducted at the Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke) and carried out as part of the Transform (Tools for natural regeneration in sustainable forest management) project funded by Luke, ArcticHubs Horizon 2020 project funded by the EU (Grant Agreement No. 869580), and REBOUND project funded by Strategic Research Council within the Research Council of Finland (decisions No 358482 + 358497).

References

Ackemo J (2018) Naturlig trädföryngring och epifytiska hänglavar 10 år efter en avverkning i schackruteform. [Natural tree regeneration and epiphytic lichens 10 years after a Chequered-Gap-cutting]. Master Thesis, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Department of Forest Biomaterials and Technology, Umeå. https://urn.fi/urn:nbn:se:slu:epsilon-s-9306.

Akujärvi A, Hallikainen V, Hyppönen M, Mattila E, Mikkola K, Rautio P (2014) Effects of reindeer grazing and forestry on ground lichens in Finnish Lapland. Silva Fenn 48, article id 1153. https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.1153.

Armleder HM, Stevenson SK (1994) Using Alternative silvicultural systems to integrate mountain caribou and timber management in British Columbia. Rangifer Spec Issue 9: 141–148. https://doi.org/10.7557/2.16.4.1235.

Boudreault C, Coxson D, Bergeron Y, Stevenson S, Bouchard M (2013) Do forests treated by partial cutting provide growth conditions similar to old-growth forests for epiphytic lichens? Biol Conserv 159: 458–467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2012.12.019.

Brooks ME, Kristensen K, Benthem KJ van, Magnusson A, Berg CW, Nielsen A, Skaug HJ, Mächler M, Bolker BM (2017) glmmTMB balances speed and flexibility among packages for zero-inflated generalized linear mixed modeling. R J 9: 378–400. https://doi.org/10.32614/RJ-2017-066.

Brunner A, Valkonen S, Goude M, Holt Hansen K, Erefur C (2025) Definitions and Terminology: what is continuous cover forestry in Fennoscandia? In: Continuous cover forestry in boreal Nordic countries. Springer, Cham, pp 11–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-70484-0_2.

Cajander AK (1926) The theory of forest types. Acta For Fenn 29, article id 7193. https://doi.org/10.14214/aff.7193.

Campbell J, Coxson DS (2001) Canopy microclimate and arboreal lichen loading in subalpine spruce-fir forest. Can J Bot 79: 537–555. https://doi.org/10.1139/b01-025.

Carroll GC (1980) Forest canopies: complex and independent subsystems. In: Forests: fresh perspectives from ecosystem analysis. Oregon State Univ Pr, pp 87–107.

Coxson D, Stevenson S, Campbell J (2003) Short-term impacts of partial cutting on lichen retention and canopy microclimate in an Engelmann spruce – subalpine fir forest in north-central British Columbia. Can J For Res 33: 830–841. https://doi.org/10.1139/x03-006.

Dettki H, Esseen P-A (1998) Epiphytic macrolichens in managed and natural forest landscapes: a comparison at two spatial scales. Ecography 21: 613–624. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0587.1998.tb00554.x.

Dettki H, Klintberg P, Esseen P-A (2000) Are epiphytic lichens in young forests limited by local dispersal? Écoscience 7: 317–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/11956860.2000.11682601.

Esseen P-A, Coxson DS (2024) Microclimate drives growth of hair lichens in boreal forest canopies after partial cutting. For Ecol Manag 572, article id 122319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2024.122319.

Esseen P-A, Renhorn K-E (1998) Edge effects on an epiphytic lichen in fragmented forests. Conserv Biol 12: 1307–1317. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.1998.97346.x.

Esseen P-A, Renhorn K-E, Pettersson RB (1996) Epiphytic lichen biomass in managed and old-growth boreal forests: effect of branch quality. Ecol Appl 6: 228–238. https://doi.org/10.2307/2269566.

Goward T (2003) On the dispersal of hair lichens (Bryoria) in high-elevation oldgrowth conifer forests. Can Field-Nat 117: 44–48. https://doi.org/10.5962/p.353857.

Hair JFJr, Anderson RE, Tatham RL, Black WC (1998) Multivariate data analysis 5th edition. Prentice hall, Upper Saddle River.

Hair JFJr, Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M, Danks NP, Ray S (2021) Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using R. A workbook. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-80519-7.

Hallikainen V, Hökkä H, Hyppönen M, Rautio P, Valkonen S (2019) Natural regeneration after gap cutting in Scots pine stands in northern Finland. Scand J For Res 34: 115–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/02827581.2018.1557248.

Hartig F (2021) DHARMa: residual diagnostics for hierarchical (multi-level / mixed) regression models. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/DHARMa/index.html.

Hayward GD, Rosentreter R (1994) Lichens as nesting material for northern flying squirrels in the Northern Rocky Mountains. J Mammal 75: 663–673. https://doi.org/10.2307/1382514.

Helle T, Saastamoinen O (1979) The winter use of food resources of semi domestic reindeer in northern Finland. Commun Finn For Res Inst 95. https://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi-metla-201207171126.

Horstkotte T, Moen J, Lämås T, Helle T (2011) The legacy of logging – estimating arboreal lichen occurrence in a boreal multiple-use landscape on a two century scale. PLOS ONE 6, article id 28779. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0028779.

Jaakkola LM, Helle TP, Soppela J, Kuitunen MT, Yrjönen MJ (2006) Effects of forest characteristics on the abundance of alectorioid lichens in northern Finland. Can J For Res 36: 2955–2965. https://doi.org/10.1139/x06-178.

Jokinen P, Pirinen P, Kaukoranta J-P, Kangas A, Alenius P, Eriksson P, Johansson M, Wilkman S (2021) Climatological and oceanographic statistics of Finland 1991–2020. Finnish Meteorological Institute, Helsinki. https://doi.org/10.35614/isbn.9789523361485.

Kalela A (1961) Waldvegetationszonen Finnlands und ihre klimatischen Paralleltypen. Arch Soc Vanamo 16 :65–83.

Kivinen S, Moen J, Berg A, Eriksson Å (2010) Effects of modern forest management on winter grazing resources for reindeer in Sweden. Ambio 39: 269–278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-010-0044-1.

Köppen W (1936) Das geographische System der Klimate. In: Köppen W, Geiger R (eds) Handbuch der Klimatologie. Verlag von Gebrüder Borntrager, Berlin, pp 1–44.

Kumpula J, Colpaert A, Tanskanen A, Anttonen M, Törmänen H, Siitari J (2006) Porolaidunten inventoinnin kehittäminen – Keski-Lapin paliskuntien laiduninventointi vuosina 2005–2006. [Developing reindeer pasture inventory – Pasture inventory in the reindeer herding districts in Middle-Lapland during 2005 –2006]. Finnish Game and Fisheries Research Institute, Helsinki. https://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:951-776-546-0.

Kumpula J, Siitari J, Siitari S, Kurkilahti M, Heikkinen J, Oinonen K (2019) Poronhoitoalueen talvilaitumet vuosien 2016–2018 laiduninventoinnissa. [Winter Pastures of the Reindeer Herding Area in the Pasture Inventory of 2016–2018]. Natural Resources Institute Finland, Helsinki. https://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-326-753-4.

Kumpula J, Jokinen M, Siitari J, Siitari S (2020) Talven 2019–2020 sää-, lumi- ja luonnonolosuhteiden poikkeuksellisuus ja vaikutukset poronhoitoon. [The Exceptional Weather, Snow, and Natural Conditions of Winter 2019–2020 and Their Effects on Reindeer Husbandry]. Natural Resources Institute Finland, Helsinki. https://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-380-023-6.

Kuusinen M, Siitonen J (1998) Epiphytic lichen diversity in old-growth and managed Picea abies stands in southern Finland. J Veg Sci 9: 283–292. https://doi.org/10.2307/3237127.

Lesica P, McCune B, Cooper SV, Hong WS (1991) Differences in lichen and bryophyte communities between old-growth and managed second-growth forests in the Swan Valley, Montana. Can J Bot 69: 1745–1755. https://doi.org/10.1139/b91-222.

Lohtander K (2011) Mitä jäkälät ovat? [What are lichens?] In: Stenroos S, Ahti T, Lohtander K, Myllys L (eds) Suomen Jäkäläopas. [The Lichen flora of Finland]. Museum of Natural Science, Helsinki, pp 13–15.

Lommi S (2011) Jäkälien elinympäristöt. [Habitats of lichens]. In: Stenroos S, Ahti T, Lohtander K, Myllys L (eds) Suomen Jäkäläopas. [The Lichen flora of Finland]. Museum of Natural Science, Helsinki, pp 35–43.

Lüdecke D (2018) ggeffects: tidy data frames of marginal effects from regression models. J Open Source Softw 3, article id 772. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.00772.

Lüdecke D, Ben-Shachar MS, Patil I, Waggoner P, Makowski D (2021) performance: An R package for assessment, comparison and testing of statistical models. J Open Source Softw 6, article id 3139. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.03139.

Mäntyranta H (2014) Clearcut areas are astonishingly small. Forest.fi. https://forest.fi/article/clearcut-areas-are-astonishingly-small/. Accessed 19 August 2024.

Metsälaki (1996) Suomen säädöskokoelma 1093/1996. [Forest Act 1996]. Suomen Eduskunta, Helsinki. https://www.finlex.fi/fi/lainsaadanto/1996/1093.

Miettinen J, Hallikainen V, Valkonen S, Hökkä H, Hyppönen M, Rautio P (2024) Natural regeneration and early development of Scots pine seedlings after gap cutting in northern Finland. Scand J For Res 39: 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/02827581.2024.2303022.

Miina J, Kumpula J, Tyrväinen L (2020) Metsien luonnontuotteet, virkistyskäyttö ja porolaitumet jatkuvapeitteisessä ja jaksollisessa kasvatuksessa. [Non-timber forest products, recreational use, and reindeer pastures in continuous-cover and rotation forestry]. Metsätieteen Aikakauskirja, article id 10345. https://doi.org/10.14214/ma.10345.

Myllys L (2011) Jäkälien rakenne. [Structure of lichens]. In: Stenroos S, Ahti T, Lohtander K, Myllys L (eds) Suomen Jäkäläopas. [The Lichen flora of Finland]. Museum of Natural Science, Helsinki, pp 17–23.

Nash THH (eds) (2008) Lichen biology 2nd edition. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Nirhamo A, Pykälä J, Jääskeläinen K, Kouki J (2023) Habitat associations of red-listed epiphytic lichens in Finland. Silva Fenn 57, article id 22019. https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.22019.

Peel MC, Finlayson BL, McMahon TA (2007) Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 11: 1633–1644. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007.

Pettersson RB, Ball JP, Renhorn K-E, Esseen P-A, Sjöberg K (1995) Invertebrate communities in boreal forest canopies as influenced by forestry and lichens with implications for passerine birds. Biol Conserv 74: 57–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-3207(95)00015-V.

Peura M, Burgas D, Eyvindson K, Repo A, Mönkkönen M (2018) Continuous cover forestry is a cost-efficient tool to increase multifunctionality of boreal production forests in Fennoscandia. Biol Conserv 217: 104–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2017.10.018.

Pike LH (1978) The importance of epiphytic lichens in mineral cycling. Bryologist 81: 247–257. https://doi.org/10.2307/3242186.

Pukkala T, Lähde E, Laiho O (2012) Continuous cover forestry in Finland – recent research results. In: Pukkala T, von Gadow K (eds) Continuous cover forestry. Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, pp 85–128. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-2202-6_3.

Rikkonen T, Turunen M, Rautio P, Hallikainen V (2023) Multiple-use forests and reindeer husbandry – case of pendulous lichens in continuous cover forests. For Ecol Manag 529, article id 120651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2022.120651.

Rominger EM, Allen-Johnson L, Oldemeyer JL (1994) Arboreal lichen in uncut and partially cut subalpine fir stands in woodland caribou habitat, northern Idaho and southeastern British Columbia. For Ecol Manag 70: 195–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-1127(94)90086-8.

Rytkönen A-M, Saarikoski H, Kumpula J, Hyppönen M, Hallikainen V (2013) Metsätalouden ja poronhoidon väliset suhteet Ylä-Lapissa – synteesi tutkimustiedosta. [Interactions between forestry and reindeer husbandry in Upper Lapland – synthesis of research data]. Finnish Game and Fisheries Research Institute, Helsinki. ISBN 978-951-303-025-1.

Snowdon P (1991) A ratio estimator for bias correction in logarithmic regressions. Can J For Res 21: 720–724. https://doi.org/10.1139/x91-101.

Stark S, Tuomi J, Strömmer R, Helle T (2003) Non-parallel changes in soil microbial carbon and nitrogen dynamics due to reindeer grazing in northern boreal forests. Ecography 26: 51–59. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0587.2003.03336.x.

Stevenson SK (1985) Enhancing the establishment and growth of arboreal forage lichens in intensively managed forests: problem analysis. Ministries of Environment and Forests, Victoria.

Stevenson SK (1988) Dispersal and colonization of arboreal forage lichens in young forests. Ministries of Environment and Forests, Victoria.

Stevenson SK, Coxson DS (2003) Litterfall, growth, and turnover of arboreal lichens after partial cutting in an Engelmann spruce – subalpine fir forest in north-central British Columbia. Can J For Res 33: 2306–2320. https://doi.org/10.1139/x03-161.

Stevenson SK, Coxson DS (2007) Arboreal forage lichens in partial cuts – a synthesis of research results from British Columbia, Canada. Rangifer 27: 155–165. https://doi.org/10.7557/2.27.4.342.

Stone I, Ouellet J-P, Sirois L, Arseneau M-J, St-Laurent M-H (2008) Impacts of silvicultural treatments on arboreal lichen biomass in balsam fir stands on Québec’s Gaspé Peninsula: implications for a relict caribou herd. For Ecol Manag 255: 2733–2742. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2008.01.040.

Swedish Forest Agency (2024) 09. Mean, median and 95th percentile in (ha) for annual final harvesting within notification greater than or equal to 0.5 hectares by region, owner category, variable and year by region, ownership class, variable and year. [Dataset]. http://pxweb.skogsstyrelsen.se/pxweb/en/Skogsstyrelsens%20statistikdatabas/Skogsstyrelsens%20statistikdatabas__Avverkning/JO0312_09.px/table/tableViewLayout2/?rxid=03eb67a3-87d7-486d-acce-92fc8082735d. Accessed 19 August 2024

Turunen MT, Rasmus S, Järvenpää J, Kivinen S (2020) Relations between forestry and reindeer husbandry in northern Finland – perspectives of science and practice. For Ecol Manag 457: 117677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2019.117677.

Valkonen S (2020) Metsän jatkuvasta kasvatuksesta. [About continous cover forestry]. Metsäkustannus, Helsinki.

Venables WN, Ripley BD (2002) Modern applied statistics with S. Springer, New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-21706-2.

Wickham H (2016) ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. In: Gentleman R, Hornik K, Parmigiani G 3rd edition. Springer, New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24277-4_9.

Zuur AF, Ieno EN, Walker NJ, Saveliev AA, Smith GM (2009) Mixed effects models and extensions in ecology with R. J Stat Softw 32: 1–3. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v032.b01.

Total of 65 references.