Networks in international opportunity recognition among Finnish wood product industry SMEs

Hietala J., Hänninen R., Kniivilä M., Toppinen A. (2019). Networks in international opportunity recognition among Finnish wood product industry SMEs. Silva Fennica vol. 53 no. 4 article id 10151. https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.10151

Highlights

- In line with earlier literature, we found the networks in our study to positively impact international opportunity recognition

- Despite the reliance on various network forms and levels, a strategic stance towards opportunity recognition can be characterized as being more reactive than proactive

- Institutional networks represented a more systematic way of recognizing international opportunities among case companies.

Abstract

Bioeconomy development will create new opportunities for firms operating in the international wood products markets, and identifying and exploiting these opportunities is emphasized as a key concept to achieving business success. Our study will attempt to address a gap in the literature on sawmill industry business development from the viewpoint of international opportunity recognition. The aim of our study is to provide a holistic description on how small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the wood products industry recognize and exploit international business opportunities, and how they utilize network perspectives in this context. The subject was examined through Finnish wood product industry SMEs by interviewing 11 managers and industry representatives. The results suggest that SMEs recognize international opportunities reactively per se. Social networks formed in professional forums were an important information channel for identifying international opportunities. Through vertical business networks, such as sales agents, firms have been able to increase their international market presence and free their own resources for other important activities. Horizontal dyadic business networks were seen to facilitate new international opportunities through cooperation, while excessive reliance on vertical networks raised concerns and seemed not to be effective in international opportunity recognition. Institutional networks formed a systematic way of recognizing international opportunities, but more so at the initial market entry stage.

Keywords

wood products;

business networks;

institutional networks;

internationalization;

opportunity recognition;

social networks

-

Hietala,

United Bankers, Aleksanterinkatu 21 A, FI-00100 Helsinki, Finland

E-mail

jyri.hietala@unitedbankers.fi

- Hänninen, Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke), Bioeconomy and environment, Latokartanonkaari 9, FI-00790 Helsinki, Finland E-mail riitta.hanninen@luke.fi

- Kniivilä, Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke), Bioeconomy and environment, Latokartanonkaari 9, FI-00790 Helsinki, Finland E-mail matleena.kniivila@luke.fi

- Toppinen, University of Helsinki, Helsinki Institute of Sustainability Science, Latokartanonkaari 7, P.O. 27, FI-00014 University of Helsinki, Finland E-mail anne.toppinen@helsinki.fi

Received 10 February 2019 Accepted 2 December 2019 Published 12 December 2019

Views 107943

Available at https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.10151 | Download PDF

Supplementary Files

1 Introduction

Wood product industries’ markets are shaped, in particular, by growing interest in industrial wood construction. For example, wooden multistory construction in the Nordic countries offers a new opportunity for these markets (e.g. Toppinen et al. 2018). More environment- and climate-friendly options are needed to improve the sustainability of many present construction solutions.

Bioeconomy development is an important driver in the Finnish economic growth strategy (The Finnish Bioeconomy Strategy 2014). Statistics (Natural Resources Institute Finland) show the forest sector to account for over one-third of the total bioeconomy output of 64.4 billion (109) euros in 2016. Emerging bioeconomy requires renewal and probably transformation of the operating practices utilized by wood products industries. In addition, product markets are sensitive to cyclical fluctuations, and companies may have inadequate resources to track all changes or identify new market opportunities. However, identifying new business opportunities is a key factor in seeking competitive advantage, for which network-based business models may offer one important solution. Our study provides information on how Finnish small and medium-sized (SME) wood products industry firms recognize and exploit international business opportunities and how they utilize various network perspectives. Our study also tries to fill the gap in the literature on sawmill industry business development from the viewpoint of international opportunity recognition.

The wood products industry is a key sector in the Finnish forest-based bioeconomy, with an output of six billion (109) euros and covering a 9.0 percent share of the total output of the Finnish bioeconomy. The importance of SME firms is highlighted, as they account for over one-third (38.3% in 2017) of the Finnish wood products industry’s turnover (Statistics Finland) along with offering a significant source of employment. From the three wood products industry sectors, i.e. sawnwood, wood-based panels, and joinery, sawnwood is most important in Finland in terms of production volumes. Limited domestic market demand has both enabled and created an incentive for the sawnwood industry to internationalize more aggressively than many other industries. Accordingly, in 2017 nearly every (98%) SME sawmill had direct exports. Yet only 7% of the SME sawmills were strongly growth-oriented (SME Sector Report 2017). The existing strong international presence of the sawnwood industry thus appears to not be directly correlated with future growth prospects.

Bioeconomy emphasizes high-added-value products as a source of economic growth (The Finnish Bioeconomy Strategy 2014). In global wood product markets, commodity sawnwood has suffered from declining per capita consumption, for which one expected reason has been the substitution of sawnwood for more added-value construction materials such as wood-based panels (Hetemäki and Hurmekoski 2016). Additionally, the output of value-added products, such as furniture and wooden houses, are expected to surpass sawnwood in the VTT (2018) scenarios. This indicates increasing market competition, especially in the case of sawmills. Consequently, without renewal the sawmill industry may potentially be unable to fully exploit the opportunities created by the bioeconomy.

The sawmill industry is a traditional low-margin and high-volume sector, where the competitiveness of companies has often been based on cost-effectiveness at the beginning of the production chain, e.g. in operations such as wood procurement and production processes of sawn timber (Toppinen et al. 2013). Firm strategies are typically not guided by customer needs (Makkonen and Sundqvist-Andberg 2017). Most previous research on Finnish sawmill firms has concerned factors in their operational environment such as the most significant costs or exchange rate changes (Hietala et al. 2013; Pöyry 2013; Mutanen and Viitanen 2015). At the company level, competitiveness has been analyzed by studying environmental communication strategies, marketing, and business management capabilities (Lähtinen et al. 2009; Toppinen et al. 2011; Räty et al. 2015). Toppinen et al. (2011) investigated the strategic cooperation of sawmills from the competitiveness viewpoint.

Network-based business models can provide a new perspective (e.g. Kontinen and Ojala 2011b) for seeking competitive advantage by identifying new international business opportunities. Previous studies on the competitiveness of the sawmill industry do not provide answers to this question. Certain earlier studies (Marttila and Ollonqvist 2010; Hurmekoski et al. 2015) emphasize the need and importance of value chain management and cooperation related to promoting wood construction.

Earlier literature suggests that networks are in use between Finnish sawmills, but these tend to be more related to upstream activities or targeting partnerships with machinery producers, and aiming for efficiency improvements rather than more strategic business-related issues (Toppinen et al. 2011; Mattila et al. 2016). Vertical integration and the share of higher-value-added products has had a minor role, although these have been found to correlate positively, especially with the financial results of companies (Lähtinen et al. 2008; Brege et al. 2010; Nybakk et al. 2011). Networks could play an important part in the future of the Finnish wood products industry, creating opportunities for growth and internationalization, especially for SMEs (Mattila et al. 2016). Various network types offer various possibilities: formal or informal business, social, and institutional networks that can be horizontally or vertically oriented in the value chain.

The objectives of the study are to examine how small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the Finnish wood products industry recognize and exploit international business opportunities, and how they utilize networks in this context. Two research questions are presented:

Identification and creation of international business opportunities: What is the role of networks in the Finnish SME sawmills to recognize international opportunities?

Types of networks used: what types of networks are used by the SMEs to identify and create new international business opportunities?

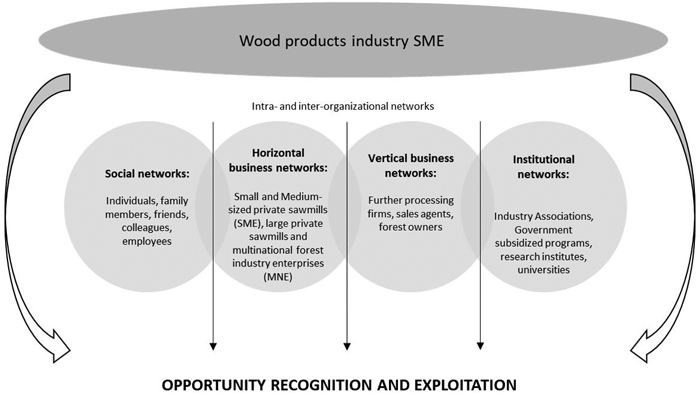

The analysis is based on the network theory of internationalization combined with the theory of international opportunity recognition emphasizing the use of networks by SMEs. As a conceptual contribution, this helps to clarify the evolving concept of bioeconomy and how the SMEs may contribute to meeting related policy goals in terms of growth and employment. In distinction to previous research networks are approached by distinguishing horizontal and vertical networks (Fig. 1). The results of our study are useful for wood products industry SMEs seeking to develop their operations to better exploit the growth and transformation of the sector. In a broader picture, the results of our research strongly link to the development of the entire Finnish wood products industry and contribute to the realization of the Finnish bioeconomy growth targets.

Fig. 1. Networks in the study (modified from Oparaocha 2015).

2 Material and methods

2.1 Theoretical framework

This study provides information on how SME wood products companies based in Finland recognize international business opportunities. Our approach is holistic, with emphasis on the use of networks by wood products industry SMEs. The research focuses on social networks (ties), business networks, and institutional networks based on findings from previous research literature (Fig. 1). Business networks are approached by distinguishing two types: horizontal and vertical networks. The theoretical base of the analysis draws from the network theory of internationalization (Johansson and Mattson 1988; Johansson and Vahlne 2009) and especially the role of different networks (Oparaocha 2015) and the theory of international opportunity recognition.

In their review article, Angelsberger et al. (2017) emphasize the need for new, also quantitative research on international opportunity recognition, which together with the concept of international opportunity still needs research to clarify the theoretical definitions. Opportunity recognition can be viewed from different perspectives, but definitions are often missing in most empirical studies. In this study, we analyze opportunity recognition in the international context, where international opportunity recognition is simply referred to as the way novel business opportunities in international markets are recognized by a company (i.e. personnel in the company) located in the domestic market. International opportunity can arise from either a novel product in a new or existing international market or an existing product in a new international market. Opportunities can thus be recognized both as the result of a company’s internal proactive search along with alertness to changes in the operating environment, technology, etc..

Opportunity recognition as a concept refers to a new type of reconciliation of market needs and resources, whereas international opportunity recognition refers to the phenomenon in an international context. Ellis (2011) defines international opportunity as the chance to exchange with new partners in new foreign markets. These partners can be existing or new customers, brokers, or contract manufacturers. Chandra et al. (2009) define internationalization as “the recognition and exploitation of entrepreneurial opportunity that leads to new international market entry”. Under this definition internationalization thus encompasses not only the identification, but also the exploitation of the opportunity.

The roots of opportunity recognition theory lie in economic theory, and particularly in the doctrines of Austrian economics. Schumpeter (1934) classifies opportunities into new organizational structures, new markets, new products and services, new production methods, and new raw materials. Opportunities may arise, for example, as a result of a change in the market, technology, or legislation, or elsewhere in the operating environment. Equally, the process can initiate from the company’s own need to search for new business opportunities (Angelsberger et al. 2017).

Much of the theory and previous studies on opportunity recognition (Shane and Venkataraman 2000; Ardichvili et al. 2003; Shane 2003; Zahra et al. 2005) emphasize the entrepreneur’s role in recognizing opportunities. For example, the entrepreneur’s personal qualities, social contacts, prior knowledge and capabilities are factors that can enhance a firm’s ability to recognize opportunities. Information is another key aspect in opportunity recognition. Schumpeter (1934) emphasizes the importance of new information on the market which could facilitate opportunity recognition, while Kirzner (1973) suggests that asymmetric information on the market allows for better identification of new opportunities.

In accordance with aforementioned views, the process of recognizing opportunities can result from both a more systematic intentional search (activeness) and entrepreneurial alertness (reactiveness) to changes in the operating environment (Ardichvili et al. 2003; Chandra et al. 2009). For example, a limited domestic market can be the driving force for a firm to search for international opportunities, while recognizing an opportunity through changes in market demand would be more reactive in nature.

International opportunity recognition is the process that initiates internationalization, or more specifically, exploitation of the opportunity. As Chandra et al. (2009) bring forward, literature on internationalization has paid very little attention to international opportunity recognition. In the process-based Uppsala model (Johanson and Vahlne 1977), emphasis is given more to the actual internationalization phase occurring after the opportunity has been recognized. In the model, a company’s internationalization is described as a progressive process where, due to firm uncertainty and risk avoidance, internationalization initiates from psychologically (culture, language, etc.) near markets and advances to more distant markets through accumulated experience. Johanson and Vahlne (1990, 2006, 2009) have later revised the model to better explain the opportunity identification process and to match today’s global business environment. More recently, Hohenthal et al. (2014) also found that experiential network knowledge, and knowledge about the importance of customers and competitors in the network, influence the value of business relationships in a foreign market.

The view of Johanson and Vahlne (2009) stems from business network research and defines markets as networks of relationships between firms. In the revised model, the “insidership” of a company to relevant networks explains internationalization rather than the psychological distance of a market. In line with the network perspective (Johanson and Matsson 1988), either existing or new networks allow companies to compensate for intra-organizational resource constraints, acting as bridges to international markets. The model of internationalization complements opportunity recognition theory by incorporating the business networks view with social networks, emphasizing the role of trust, learning, and dissemination of knowledge.

Opportunity recognition can be viewed from different perspectives, and the spectrum of previous studies can be regarded as rather extensive. With regard to networks, previous research has focused on social, business, and institutional networks. Research on social networks has shown that social ties can promote the recognition of SMEs’ international opportunities by providing relevant information of business opportunities, potential business partners, industry, and technology (Shane 2000; Ellis 2011). Social networks have been found to reduce the risk and uncertainty of an internationalizing company (Zain and Ng 2006), improve the reputation and popularity of an SME in particular (Ciravegna 2014), and social ties have been found to be relevant when institutions are undeveloped (e.g. Rangan 2000).

According to Agndal et al. (2008), both weak and strong social ties are important in recognizing international opportunities. Previous literature suggests that particularly weak social ties, in line with Granovetter (1973), are able to provide such information that helps in opportunity recognition. Weak ties obtained from e.g. international trade fairs and other professional forums are important for internationalizing SMEs (Ellis 2000; Coviello 2006; Ozgen and Baron 2007; Ellis 2011; Kontinen and Ojala 2011a; Zaefarian et al. 2016). Chandra et al. (2009) find support for both strong and weak ties in SMEs’ recognition of first international opportunity, with weak ties allowing the gathering of relevant data and strong ties enabling the transfer of information to the correct people. The importance of social networks can also change over time and Crick and Spence (2005) accordingly recognized that SMEs should actively seek for new networks after market entry.

The network theory of internationalization emphasizes the importance of a firm’s inter-organizational networks. Such business networks can produce unique information in addition to that provided by social networks and can therefore facilitate internationalization (e.g. Burt 2004). In the study by Kontinen and Ojala (2011b), family-owned SMEs recognized international opportunities through both business networks and social ties. In Zaefarian et al. (2016), SMEs recognized their first international opportunity through social networks and afterwards through business networks.

The institutional theory on the other hand implies that companies can create networks with institutions to e.g. access resources they are unable to gain via social and business networks. Internationalizing SMEs can need financial support, specific information, and contacts from the foreign market or licensing assistance from domestic institutions (Narooz and Child 2017). The Finnish export promotion program (Wood from Finland), organized by Finpro, is an example of a domestic institution that most recently helped SMEs in accessing Chinese sawnwood markets. Seminars, and trips to trade fairs and other events increased the reputation of Finnish sawnwood, creating an impetus for Finnish sawnwood industry SMEs to begin conducting business in China. The organized events were coordinated in such a way that relevant contacts were present. Social ties formed with potential customers during the events have been of prime importance for possible future trading.

Opportunities can be identified through proactive searching or reactive finding. Crick and Spence (2005) observed that companies entered international markets by reacting to unexpected inquiries. Similar results were obtained by Kontinen and Ojala (2011b) and Santos-Álvarez and García Merino (2010). On the other hand, a shortage in existing networks tends to cause proactive behavior when establishing new networks to enter international markets (Ojala 2009). So-called born global companies have also been found to actively use existing or new social networks when striving for international markets (Vasilchenko and Morrish 2011). In Zaefarian et al. (2016), SMEs typically recognized their first international opportunity by accident and subsequent opportunities through active search. Piantoni et al. (2012) found SMEs to use both a systematic and reactive approach.

2.2 Data and methodology

The study utilizes a qualitative research approach. Primary data are composed of 11 theme interviews conducted between May and December 2017. A list of all respondents is presented in Table 1. Theme interviews utilizing a semi-structured interview protocol were applied to form flexibility and a profound understanding of the phenomenon under examination (Yin 2014). The questionnaire was formulated with guidance from the main research questions and theoretical framework of the study, and the main themes are presented in Supplementary file S1. Topics discussed during the interviews were partially influenced by the accumulated information from previous interviews and by each interviewee’s own emphasis.

| Table 1. Research sample. | ||||

| Company / Organization | Annual turnover, MEUR | Personnel number | Interviewee position | |

| 1 | Sawnwood company | 25–50 | 0–50 | CEO |

| 2 | Sawnwood company | 75–100 | 150–200 | CEO |

| 3 | Sawnwood company | 0–25 | 0–50 | CEO |

| 4 | Sawnwood company | 75–100 | 100–150 | CEO |

| 5 | Sawnwood company | 0–25 | 0–50 | CEO, Export Manager |

| 6 | Sawnwood company | 25–50 | 50–100 | Business Manager |

| 7 | Sawnwood export company | - | - | CEO |

| 8 | Wood products company | 25–50 | 0–50 | CEO |

| 9 | Sawnwood Industry association | - | - | CEO, Project Manager |

| 10 | Wood products industry association | - | - | CEO |

| 11 | Export promotion organization | - | - | Program Manager |

Seven SME wood products companies, a purely export company, two wood products industry associations, and an export promotion association were interviewed. The sample size can be considered sufficient for a multiple case study (Miles and Huberman 1994). Case companies were chosen with purposive sampling and the snowball technique to achieve good representation of the population. All case companies fulfill the definition of an SME with less than 250 employees and a balance sheet total of less than 43 million euros (European Commission 2003). Interview data from the associations were used as secondary material and as a means to triangulate certain findings. All interviewees represented the management level (CEO, Business Director, Export Manager, Project Manager, and Program Manager), implying respondents presumably have good knowledge of the studied topics.

Two interviewees were concurrently present during two of the interviews, while the rest were conducted one-on-one. Each interview was held by the same person to ensure a similar research setting in each interview. Nine of the interviews were conducted face-to-face and two interviews were conducted by phone due to tight schedules and long distances of the interviewees. Interview length ranged between 33 and 91 minutes and averaged 60 minutes. All but one of the company interviews were recorded and transcribed for further analysis.

The analysis follows Miles and Huberman’s (1994) method recommended for conducting a systematic qualitative data analysis. The method has recently been used in the case of sawnwood/wood products industry case e.g. by Makkonen and Sundqvist-Andberg (2017), who studied customer value creation. The analysis progresses through sequential steps from data reduction and display to drawing out and verifying the conclusions. Accordingly, data reduction was carried out first by coding the transcribed data into meaningful subsets. Next the data were displayed by summarizing the coded data into fewer themes and tabulating the data with a simple matrix with rows representing themes and columns representing the SME companies. Conclusions were drawn based on similarities and differences (patterns) within and across cases, and support for the conclusions were finally seeked by critically reflecting the findings with previous research results and theory. In practice, the analysis advanced in an iterative manner, where previous steps were visited several times during the process.

In the study, careful documentation was used to ensure the reliability of the results. During the interviews, the questions were thoroughly explained in the case of unclear interpretation of concepts. Despite evidence being drawn from a limited number of interviews, our data saturated well in the analysis, reflecting a rather homogenous industry-dominant logic. Still, generalization of our findings should be avoided, due to uncertainty related to the interview-based qualitative study approach. The internal validity was later approached by interpreting the data based on the theoretical thinking drawn from Fig. 1.

3 Results

3.1 International opportunity recognition in Finnish wood product industry SMEs

In all case companies, both export sales managers and the managing or business director were responsible for export sales. In addition to company-specific factors, market-based differences in trade affect the way exports are organized in companies. All companies also utilize, at least to some extent, sales agents or other intermediaries, and two companies additionally have a joint venture handling their exports. Table 2 presents the summarized results classified into five themes based on main findings of the interviews corresponding to the literature of opportunity recognition. Selected quotes of the respondents have been included to further illustrate these findings.

| Table 2. Summary of the interview results associated to opportunity recognition. | |

| Emphasis on existing business and customer relationships, international opportunities mostly well known. | “This may sound foolish, but I don’t have to search for new customers and new markets, because I am able to sell fairly well to our regular customers or at least through standard channels“ (Company 3) |

| ”Inquiries [from potential customers] are arriving, but currently we don’t have a need, so we don’t act on them in any way” (Company 6) | |

| “Well, this is an old field and at least the larger companies have base knowledge, of how countries are positioned in the market. This doesn’t mean that everything has been investigated thoroughly and we may be missing something relevant [...], but the sales team is constantly doing their job tracking, listening to hints, looking at the statistics, and following the general economic development…” (Company 4) | |

| New international opportunities often recognized through serendipity | “Suddenly, almost out of nowhere, while mainly selling small quantities to French importers, we realized it was possible to go directly to industrial end-users. That was something new. These [opportunities] just come from somewhere.” (Company 1) |

| “If you think of New Zealand […] it wouldn’t be worthwhile to explore [the market] costwise […] These happen more through coincidence.” (Company 6) | |

| Direct customer contacts and market information identified as ways to recognize new international opportunities proactively | ”At one point we hired a new person to take care of the routine work, while the older, more experienced personnel were engaged in building new customer relationships in new markets. This should, of course, be happening constantly.” (Company 2) |

| ”Of course, if we had an employee abroad constantly searching and looking, we would be receiving the information differently.” (Company 3) | |

| Limited resources often restrict possibilities of SMEs’ international opportunity recognition and exploitation | ”We don’t have such a great need [to search for new markets], we prefer to wait and see what others do, and then possibly follow them. ” (Company 6) |

| ”The fact remains that creating market demand for high-quality sawn timber products, for example through marketing measures, is not in our hands. It is just too arduous [resource-wise]. Typically, the markets have developed little by little. ” (Company 1) | |

| New opportunities exploited with caution and without any major transformations or innovations | ”These are risky projects, so for us the conclusion is to wait and see, and I would argue that this also applies to quite a few others.” (Company 4) |

| ”Further processing companies are continuously searching for something new [...] trying to innovate. We are not planning to transform our production. I don’t think that we can be innovative in the same way in our own production, except that we are trying to make the most of what we are doing on this site.” (Company 3) | |

| ”After all, we have around 400 products per wood species, so if a potential market emerges, it is likely to be found from our production.” (Company 2) | |

The managers in the interviewed companies all emphasized existing long-term customer relationships, and did not perceive an actual need to search for new business opportunities. This result is consistent with the network perspective (Johanson and Mattson 1988), according to which trading is dominantly based upon existing producer-customer relations. Building and developing a long-term customer relationship has expanded the commitment of both parties to such an extent that neither party is ready to give it up easily. Certain interviewees even stressed that their production strategy was steered to a large extent according to the needs of existing customers. The lack of need for business with new customers can also be linked to the moderate growth strategy of these companies.

When speaking about the process of recognizing international opportunities, interviewed managers voiced, that new customer relationships have been generated largely by reacting either to direct customer contact or to queries from sales agents. As Chandra et al. (2009) point out, even in the case of luck, social networks have often contributed to a company’s competences and motivation and are in this way found to affect in the background. In many cases, chance was also considered a factor in the recognition and exploitation of new business opportunities.

One of the case companies was clearly distinct from others in respect to how opportunities are recognized and exploited. Their representative described how the company is actively seeking to grow in its international operations and systematically searches for new customers based on annual strategies formed for different market regions. This finding emphasizes the possible importance of context in interpreting results as this company produces further processed wood products and thus has a different customer base compared to other case companies.

All companies had at least to some extent systematically monitored different international markets, thus potentially enhancing international business opportunity recognition. Non-European markets such as India, Iran, the United States, and the Far East, were mentioned as the most potential markets. Europe is the main export region for Finnish sawnwood, yet Poland, mentioned twice, was the only European country brought up during the interviews. Certain companies mentioned that it typically takes time for a new market to reach a point where entry would be feasible for an SME. Sufficient demand for high-quality products was seen as a precondition. As one manager explained, customers in the traditional markets, such as Europe, are well known and in this sense do not bear any potential that others are not aware of.

Although most companies had typically not attempted to create new business opportunities systematically, or even to see this possibility in the larger markets, the establishment of the Japanese market in the 1990s was frequently mentioned as an example of a more systematic way of entering a new market. All case companies had also expanded systematically to China’s growing market through the governmentally supported export promotion program (Wood from Finland).

Certain managers recognized a need for conducting more footwork in potential markets. A few companies had tried different ways to proactively search for new customers. One company had carried out market research for the Indian market, although this did not materialize as any new customer relationships. Sending experienced export staff abroad to scan the market and create possible new customer accounts through direct business contacts had also been attempted, while another company had understood that more information would be accumulated from the market if the company had its own personnel continuously on location.

Realization of international business opportunities may be also affected by a company’s inability to exploit these opportunities. The interviewees highlighted limited resources (finance, personnel) and observed that the emergence of new customer relationships often requires a great deal of time. In this respect, it was also apparent that it is often easier for an SME to enter a market after it has first been opened up by competitors, and this was also confirmed explicitly. The interviewees felt that the first-mover advantage in market entry would fade rather quickly, which is why a wait-and-see strategy would be more appropriate in most cases.

Better understanding of customer needs can be considered a necessity for recognizing business opportunities. According to the interviews, managers did not see a great need to change existing production and thus appeared confident about the customer fit of their present products. One interviewee noted that the company had conducted its own market research some decades ago, when it had been forced to change the entire production line. Managers also mentioned the risks related to converting production and emphasized the role of further processing firms in research and development (R&D) and product innovations. Instead, one of the companies justified the status quo with the scope of their current product portfolio.

3.2 The role of networks in internationalization

The role of networks in international opportunity recognition was inquired from the companies and the main results are summarized in Table 3 together with interviewees’ quotes. The role of international sales agents was emphasized in each company’s export activities. Evidently this became a key consideration for SMEs’ international opportunity recognition, where both benefits and disadvantages were identified. Examples were given in the interviews, where first contacts with new customers were created through sales agents. Agents typically operate in a designated region, where they manage a company’s foreign sales and customer relationships. In this respect, the acquisition of new customers is also limited to these specific markets. However, completely new markets have also been opened in certain cases through agents’ social contacts.

| Table 3. Summary of the interview results associated to the role of networks in opportunity recognition. | |

| Social contacts and market presence of middlemen such as agents and export companies have facilitated internationalization | ”Our first experience from Switzerland came through our German agent, who introduced us to the Swiss market [...] then the Swiss guy took us to Austria.” (Company 5) |

| ”The Swiss market was opened by a sales agent. We suddenly came across an Austrian guy with contacts in Switzerland, who was looking for sawn timber producers that could supply enough quality to Switzerland. That is how it began.“ (Company 1) | |

| ”Agents are still present in many markets simply because of language. Germany is our largest market and if you don’t have good command of German language and cultural knowledge, it would be difficult to trade with many customers” (Company 6) | |

| ”If you think about the role of export companies, then us having more personnel than a firm of our size would normally have [...] I would say that this provides us with more contact surface, and on the other hand, we have more traditions and therefore something always bounces through.” (Company 1) | |

| Close social relationships with other sawmills’ representatives may enable co-operative networks and international opportunity recognition | ”Yes, we have specific colleagues with whom we cooperate with. I may tell them I am unable to handle this or that, and would you be interested in dealing with it. So yes, to some extent such exchanges of thoughts have been utilized.” (Company 3) |

| ”Even now, Latvia for example has begun importing from us due to Company X selling larger batches there. So suddenly we were there [in the Latvian market] [...] The same happened in Morocco” (Company 1) | |

| ”In France, we have a client whose purchases are currently so massive that we are simply unable to manufacture everything. So we delegated some to Company X, because we know that we have a trustful relationship and we know the quality of their product will certainly meet the customer’s expectations. They [Company X] were able to help us.” (Company 5) | |

| Excessive network dependency in recognizing new business opportunities should be managed | ”At worst, the agent is like a broken phone, so I don’t get the information and my messages are unnecessarily filtered to the customer.” (Company 3) |

| ”The risk related to these consortia is that [mutual] jealousy increases, taking even the fish out of the pot [a Finnish saying referring to how jealousy corrodes][…] so this will not work because there is not enough business for everyone”. (Company 4) | |

| Institutional networks have enabled a more systematic way to recognize and exploit international opportunities | ”[...] at the very beginning , with such a consortium in a market of this size, everyone managed to get further than anyone would have alone, even if great effort had been made [to reach the target] […] We have been able to reach a critical level, which has awoken the interest [of clients], and so each company’s sales work lies under this [consortium] umbrella.” (Company 4) |

| ”This event where we were in Shanghai. A large furniture trade fair was held there, drawing in wood products experts from all around China […] so we are looking for such informal networks.” (Company 3) | |

Certain interviewees questioned the role of sales agents, especially in the case of long-term customer relationships, where a company has built a relationship directly with the customer over the years and would be able to manage sales without middleperson. Similarly, the incentives of agents to search for new customers were questioned because of how they are compensated. The interviewees felt that a commission-based system only encourages maximizing the volume to a present customer and not searching for new customers. Several interviewees even stated that the use of sales agents is more a historical remnant in many markets in their business field. Examples were given of how foreign sales can nowadays be managed through social media channels and, in general, how the competency and knowledge of conducting business with foreign clients has increased in companies.

The use of agents and other middlepersons was justified especially due to their cost-efficiency. Trading houses and importers also have the ability to reduce risks related to credit losses. An SME is able to operate globally through agents and importers, even in niche markets where having your own sales representatives is not feasible. This concurrently enables allocating the firm’ resources elsewhere. Culture- and language-related factors were also considered to affect the use of middlepersons in specific markets. Although the sales forces in SMEs are nowadays well educated, the use of native-speaking personnel still has its advantages.

In some cases, the customers or other market representatives may require the use of middlepersons, so having one was not even considered the vendor’s decision. This can be related e.g. to linguistic and other cultural factors or to specific market trading principles. In the Japanese market, the strength of trading houses appears to be related to their strong position vis-à-vis end customers. Interviewees also reported anomalies in certain European and North African markets along with China, where companies are typically required to use middlepersons. Market-specific factors may thus affect trading requirements that further influence international opportunity recognition.

According to most respondents, the use of middlepersons does not have a particularly negative impact on the quantity of information received from the market. In most cases, agents were seen to manage customer queues in a positive manner. However, certain interviewees still suspected that important information was also being filtered.

In addition to vertical networks, the interviewed managers also identified horizontal business-to-business networks. The most concrete example was a jointly owned export company between two of the companies. This was found to increase cost efficiency and the general attractiveness of their product portfolios, as the partners’ products are complementary to one another. Possible negative effects related to a sales agent’s pecking order are also eliminated. Sharing sales resources was reported not only to save costs, but to also expand both partners’ social networks and thus potentially facilitate recognition of international business opportunities. Overall, formal horizontal business networks were absent between the case companies, and an explanation for this was given by its binding effect on the strategic choices of parties.

Certain case companies have had occasional informal bilateral cooperation with other SMEs. Examples were given from situations where company A has passed on customer queries to company B in circumstances where company A does not itself produce the demanded product. One company also reported that they have raised product volumes delivered to the customer by cooperating with another company producing a similar product. Additionally, one company has cooperated with a further processing firm with limited resources in export sales. This has also enabled the company to expand its product portfolio with value-added products and thus increase its overall attractiveness to customers.

The interviewees revealed that even informal cooperation has been absent between SMEs and multinational forest industry enterprises (MNEs). Networks formed with MNEs were also found unrealistic in the future due to differing business logics in producing sawn timber. However, MNEs were partially credited for opening up international opportunities for the wood products industry by improving the reputation of Finnish sawn timber and more generally the Finnish forest industry companies.

Trust in the other partner and a shared business logic were emphasized when forming informal networks between companies. Feelings of envy between companies were, on the other hand, mentioned in several interviews as an issue that could block more in-depth cooperation. The risk is emphasized especially in small markets, where partners’ products are competing substitutes.

In addition to deepening social and business networks, institutional networks can enhance the ability of SMEs to recognize and exploit international business opportunities. For example, the Wood from Finland program organized by Finpro, was highlighted in every interview as a successful example, especially evident when entering the Chinese market. Several interviewees also emphasized that the program’s success is the sum of many factors. One of the interviewed managers concluded that the support of the institutional network has accelerated access to China compared to a situation where the network did not exist. Only one manager felt that reaching the market would have been possible without assistance from the export promotion program, and had no need for a similar program in the future.

Memberships in associations and organizations along with networks with research institutes were also examples of institutional networks formed by these companies. Each company was a member of at least one main domestic industry association. When asked about the importance of these associations, the companies mentioned that the memberships have provided companies with useful market information, particularly from those markets where the company itself is not operating. Associations systematically provide information to companies, directly through statistics, and indirectly via seminars and other events organized by the associations. Social contacts formed at events in particular, have led to new international business opportunities.

One case company additionally has a membership in an international association. This has given the SME a label of certificate for their product, which is regarded as a necessity for international entrepreneurship. The same company has actively formed networks in R&D activities with a domestic university and research institute, further facilitating the SMEs international opportunity recognition and exploitation.

4 Discussion and conclusions

4.1 Development of propositions

Our study tries to fill the gap in the literature concerning sawmill industry business development from the viewpoint of international opportunity recognition. According to internationalization theory (Johanson and Mattson 1988; Johanson and Vahlne 2009; Hohenthal et al. 2014) companies can, with the use of networks, gain access to international markets by decreasing associated risks or by gaining access to external resources. By building on the empirical analysis, we have developed the following five propositions, which could be validated in more quantitatively oriented future research. To conduct international market opportunity recognition, firms require information that is not easily available in the markets. Especially for SMEs, collecting and processing market and customer information tends to be limited by available firm resources and capabilities (Angelsberger et al. 2017; Zaefarian et al. 2016).

Also in this study, we found the case companies to screen their international markets to some degree, but the process cannot be described as active (with the exception of one company). During the interviews on international opportunity recognition, managers typically referred to lacking resources. All companies focused on maintaining established long-term customers, and certain even questioned their need to find new clientele. Direct contacts, and pure serendipity, were mentioned as sources for finding novel market opportunities. Based on this, we conclude that the case sawmills in Finland have a predominantly reactive mode for recognizing international market opportunities, and we therefore arrive at our first proposition:

Proposition 1. Recognizing international opportunities among wood industry SMEs is more likely reactive than proactive.

SMEs in the sawmilling industry are currently not restricted by physical or psychic distance to markets. In fact, overseas trading has become increasingly common with the accumulated knowledge and experience. Intra-organizational resources can also be expanded with the use of vertical networks. Based on our study, the use of sales agents were justified by the managers based on the language and cultural diversity between home and the export country. This is in line with e.g. Hurmerinta et al. (2015), who found that personnel using the local language were better equipped to recognize international market opportunities. Business processes related to value-adding production are typically outsourced to occur in the export markets.

Our results on the use of vertical networks are in line with network-based internationalization theories, suggesting that access to markets is enhanced by network participation. In addition, according to Jarillo (1993), business networks can be a more capable form of organization in comparison to vertically integrated companies with respect to rapid market changes. According to the resource-based theory of the firm, the use of complementary resources can increase competitiveness, which has also been identified among the Finnish sawmills (Lähtinen et al. 2009). The long distance to the markets and end-customers, may concurrently lead to a situation where a company may not diffuse all relevant information on market (Husso and Nybakk 2010), which acts as a barrier to international opportunity recognition. Physical distance to markets also calls for more intense communication in the downstream value chain partners. Excessive reliance on sales agents may also restrict the recognition of new opportunities in the existing markets, because of their market-specific knowledge and limited geographic mobility. Sales agents may also lack proper incentives to search for new customers. This became evident during the interview discussions on the importance of finding the right type of agents, and we conclude by providing the second proposition as follows:

Proposition 2. Vertical business networks – if not used too extensively – facilitate more efficient market presence and international opportunity recognition among wood industry SMEs.

In the literature, the business network concept typically refers to business-to-business type vertical networks. However, horizantal networks can also increase firm resources and capabilities, and facilitate opportunity recognition. According to Huggins et al. (2012), these forms are often related to inter-organizational process-based cooperation, aiming at expanding firm business and profitability levels.

In our study, we identified one long-term formal horizontal business network among the case sawmills, with the addition of few shorter-term informal ones, related to increasing international business opportunities. These network activities have increased the cost-efficiency of sawmills (Lähtinen and Toppinen 2008) by expanding resources required for international market presence or by attracting a larger clientele, or simply enabled to meet customer requirements (Husso and Nybakk 2010). In line with Mort and Weerawardena (2006), network rigidity was seen as a possible obstacle when forming formal horizontal business networks. Regardless of the formality or informality of the horizontal network, a high level of trust and ability to create mutual benefits to network participants are elementary ingredients in successful cooperation. Thus we arrive at our third proposition:

Proposition 3. Horizontal business networks can help integrate firm-specific resources among wood industry SMEs, and thereby facilitate international opportunity recognition in the network.

According to previous literature, weak social ties (such as between business partners, competitors, or agents) are able to provide information that facilitates opportunity recognition. Also in our study, interviewees mentioned beneficial information from informal social networks, formed for example during trade fairs. Also, a previous study by Ozgen and Baron (2007) found a positive correlation between intra-industry social networks, and professional forums and opportunity recognition. Long-standing business relationships indicate that companies have managed to form strong ties from initially weaker social networks, as also observed in a study by Kontinen and Ojala (2011b). Thus, we arrive at our fourth proposition:

Proposition 4. The number of informal social networks among wood industry SMEs seem to effect positively on international opportunity recognition.

Domestic institutions may both support and void international opportunity recognition in multiple ways. In our study, the role of institutional support was evident and was especially mentioned in the case of establishing market position in China. Wood from Finland by Finpro appeared to create necessary support and a platform by bringing various competitors together with potential clients. In a large growth market, this has accelerated opportunity recognition and utilization. As key strategic resources, the expertise of program personnel was emphasized, confirming earlier findings by Oparaocha (2015). Based on our interviews, we realized that the importance of domestic institutions is likely to diminish over maturing market presence and the emergence of other networks. This finding is in line with Oparaocha (2015), suggesting that market entry is the most critical phase where institutional networks can be beneficial. This leads to our fifth proposition:

Proposition 5. Domestic institutional networks facilitate initial opportunity recognition in large international markets.

In line with earlier literature, we found the networks in our study to positively impact international opportunity recognition. The use of social networks increased both business contacts and access to market information, while the use of vertical networks enabled better market presence and knowledge, with firms being able to free company resources to other activities. Sales agents improved information flows, yet we concurrently observed an increased risk of losing relevant information, such as in the form of ”a broken telephone”. The dual, either formal or informal, networks have enabled direct and indirect international opportunities. The more recent institutional network around promoting wood product exporting is an example of successful systematic effort. On the downside, reliance on networks can also weaken international opportunity recognition by linking to specific strategic choices (e.g. Mort and Weerawardena 2006) or commitment to weak partners (Eriksson et al. 2014). Also in our study, one of the case companies expressed a view that formal horizontal networks can negatively impact firm’s operational structures. Generally speaking, observing opportunistic behavior, and even the emergence of negative feelings, such as envy, is possible among partners.

Despite the reliance on various network forms and levels, a strategic stance towards opportunity recognition can be characterized as being more reactive than proactive. When interpreting the findings e.g. in light of the Finnish government’s bioeconomy ambitions, the goal of increasing the export value of value-added products will not be easily met. For example, we noted that the R&D activities nearly completely lacked an emphasis on sawmills, and it was perceived as the responsibility of the downstream wood industry. This finding is also in line with results from Makkonen and Sundqvist-Andberg (2017) concerning the weakly developed customer orientation among the Finnish sawmill industry.

4.2 Future research needs

Our study brought out new empirical information on international opportunity recognition, stance towards international growth, and the accrued benefits from various network structures. Based on our results, it is not yet possible to conclude in which specific ways Finnish SME sawmills will recognize their future international market opportunities. However, the study enabled forming a holistic picture around the topic of international opportunity recognition. In addition to exploring the validity of five propositions developed from our data and analyses using more extensive data sets and in different contexts, we can recommend certain areas for future research. The role of cross-sectoral collaboration is likely strengthening as an avenue for building sustainable competitiveness with the emergence of the bioeconomy era, but this topic has currently not been studied empirically (see a review of literature by Guerrero and Hansen 2018). In addition, future research would be needed concerning company-level processes and strategies towards international opportunity recognition among larger-scale businesses. This may also be more embedded in the more systematic use of various network types, and thus provide a more elevated view on the phenomenon. Finally, research could also act as a stimulus for collaboration between more agile companies and the more risk-aversive large-scale incumbent firms in the context of bioeconomy.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge financial support received from three foundations, namely Marjatta ja Eino Kollin säätiö, Puumiesten Ammattikasvatussäätiö and Niemi-säätiö. We also appreciate editors and anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments.

References

Agndal H., Chetty S., Wilson H. (2008). Social capital dynamics and foreign market entry. International Business Review 17(6): 663–675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2008.09.006.

Angelsberger M., Kraus S., Mas-Tur A., Roig-Tierno N. (2017). International opportunity recognition: an overview. Journal of Small Business Strategy 27: 19–36.

Ardichvili A., Cardozo R., Ray S. (2003). A theory of entrepreneurial opportunity identification and development. Journal of Business Venturing 18(1): 105–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(01)00068-4.

Brege S., Nord T., Sjöström R., Stehn L. (2010). Value-added strategies and forward integration in the Swedish sawmill industry; positioning and profitability in the high-volume segment. Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research 25(5): 482–493. https://doi.org/10.1080/02827581.2010.496738.

Burt R.S. (2004). Structural holes and good ideas. American Journal of Sociology 110(2): 349–399. https://doi.org/10.1086/421787.

Chandra Y., Styles C., Wilkinson I. (2009). The recognition of first time international entrepreneurial opportunities: evidence from firms in knowledge-based industries. International Marketing Review 26(1): 30–61. https://doi.org/10.1108/02651330910933195.

Ciravegna L., Majano S.B., Zhan G. (2014). The inception of internationalization of small and medium enterprises: the role of activeness and networks. Journal of Business Research 67(6): 1081–1089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.06.002.

Coviello N.E., Cox M.P. (2006). The resource dynamics of international new venture networks. Journal of International Entrepreneurship 4(2–3): 113–132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10843-007-0004-4.

Crick D., Spence M. (2005). The internationalization of ‘high performing’ UK high-tech SMEs: a study of planned and unplanned strategies. International Business Review 14(2): 167–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2004.04.007.

Ellis P. (2000). Social ties and foreign market entry. Journal of International Business Studies 31(3): 443–469. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490916.

Ellis P.D. (2011). Social ties and international entrepreneurship: opportunities and constraints affecting firm internationalization. Journal of International Business Studies 42(1): 99–127. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2010.20.

Eriksson K., Jonsson S., Lindbergh J., Lindstrand A. (2014). Modeling firm specific internationalization risk: an application to banks risk assessment in lending to firms that do international business. International Business Review 23(6): 1074–1085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2014.06.011.

European Commission (2003). European Commission recommendation 2003/361/EC.

The Finnish bioeconomy strategy (2014). http://www.bioeconomy.fi/facts-and-contacts/material-bank/.

Granovetter M.S. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology 78(6): 1360–1380. https://doi.org/10.1086/225469.

Guerrero J., Hansen E. (2018). Cross-sector collaboration in the forest products industry: a review of the literature. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 48(11): 1269–1278. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjfr-2018-0032.

Hetemäki L., Hurmekoski E. (2016). Forest products markets under change: review and research implications. Current Forestry Reports 2(3): 177–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40725-016-0042-z.

Hietala J., Hänninen R., Toppinen A. (2013). Finnish and Swedish sawnwood exports to the UK market in the EMU regime. Forest Science 59(4): 379–389. https://doi.org/10.5849/forsci.10-122.

Hohenthal J., Johanson J., Johanson M. (2014). Network knowledge and business-relationship value in the foreign market. International Business Review 23(1): 4–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2013.08.002.

Huggins R., Johnston A., Thompson P. (2012). Network capital, social capital and knowledge flow: how the nature of inter-organizational networks impacts on innovation. Industry and Innovation 19(3): 203–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/13662716.2012.669615.

Hurmekoski E., Jonsson R., Nord T. (2015). Context, drivers, and future potential for wood-framed multi-story construction in Europe. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 99: 181–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2015.07.002.

Hurmerinta L., Nummela N., Paavilainen-Mäntymäki E. (2015). Opening and closing doors: the role of language in international opportunity recognition and exploitation. International Business Review 24(6): 1082–1094. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2015.04.010.

Husso M., Nybakk E. (2010). Importance of internal and external factors when adapting to environmental changes in SME sawmills in Norway and Finland: the manager’s view. Journal of Forest Products Business Research 7: 1–14.

Jarillo J.C. (1993). Strategic Networks: creating the borderless organisation. Butterworth Heinemann, Oxford.

Johanson J., Mattsson L.-G. (1988). Internationalization in industrial systems – a network approach. In: Hood N., Vahlne J.-E. (eds.). Strategies in global competition. Croom Helm, New York. p. 303–321.

Johanson J., Vahlne J.-E. (1977). The internationalization process of the firm – a model of knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitments. Journal of International Business Studies 8(1): 23–32. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490676.

Johanson J., Vahlne J.-E. (1990). The mechanism of internationalisation. International Marketing Review 7: 11–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/02651339010137414.

Johanson J., Vahlne J.-E. (2006). Commitment and opportunity development in the internationalization process: a note on the Uppsala internationalization process model. Management International Review 46(2): 165–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-006-0043-4.

Johanson J., Vahlne J.-E. (2009). The Uppsala internationalization process model revisited: from liability of foreignness to liability of outsidership. Journal of International Business Studies 40(9): 1411–1431. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2009.24.

Kirzner I.M. (1973). Competition and entrepreneurship. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL. 246 p.

Kontinen T., Ojala A. (2011a). International opportunity recognition among small and medium-sized family firms. Journal of Small Business Management 49(3): 490–514. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627X.2011.00326.x.

Kontinen T., Ojala A. (2011b). Network ties in the international opportunity recognition of family SMEs. International Business Review 20(4): 440–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2010.08.002.

Lähtinen K., Toppinen A. (2008). Financial performance in Finnish large and medium-sized sawmills: the effects of value-added creation and cost-efficiency seeking. Journal of Forest Economics 14(4): 289–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfe.2008.02.001.

Lähtinen K., Toppinen A., Leskinen P., Haara A. (2009). Exploring the connection between resource usage decisions and business success in case of Finnish large and medium sized sawmills. Journal of Forest Products Business Research 6.

Makkonen M., Sundqvist-Andberg H. (2017). Customer value creation in B2B relationships: sawn timber value chain perspective. Journal of Forest Economics 29(2): 94–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfe.2017.08.007.

Marttila J., Ollonqvist P. (2010). Puurakentamisen suomalais-venäläinen liiketoiminta Venäjällä -vientikaupasta verkostoihin. [Finnish-Russian wood construction business in Russia – from export to networks]. Metlan työraportteja/Working Papers of the Finnish Forest Research Institute 151. 73 p. [In Finnish]. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-40-2226-5.

Mattila O., Hämäläinen K., Häyrinen L., Berghäll S., Lähtinen K., Toppinen A. (2016). Strategic business networks in the Finnish wood products industry: a case of two small and medium-sized enterprises. Silva Fennica 50(3) article 1544. https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.1544.

Miles M.B., Huberman A.M. (1994). Qualitative Data Analysis: an Expanded Sourcebook. Sage Publications, Los Angeles, CA.

Mort G.-S., Weerawardena J. (2006). Networking capability and international entrepreneurship: how networks function in Australian born global firms. International Marketing Review 23(5): 549–572. https://doi.org/10.1108/02651330610703445.

Mutanen A., Viitanen J. (2015). Suomen sahateollisuuden kansainvälinen kustannuskilpailukyky 2000-luvulla. [International cost competitiveness of the Finnish sawnwood industry in the 2000s] Metsätieteen aikakauskirja 2/2015: 69–85. [In Finnish]. https://doi.org/10.14214/ma.6530.

Narooz R., Child J. (2017). Networking responses to different levels of institutional void: a comparison of internationalizing SMEs in Egypt and the UK. International Business Review 26(4): 683–696. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2016.12.008.

Natural Resources Institute Finland. Finnish bioeconomy in numbers. https://www.luke.fi/en/natural-resources/finnish-bioeconomy-in-numbers/.

Nybakk E., Crespell P., Hansen E. (2011). Climate for innovation and innovation strategy as drivers for success in the wood industry: moderation effects of firm size, industry sector, and country of operation. Silva Fennica 45(3): 415–430. https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.110.

Ojala A. (2009). Internationalization of knowledge-intensive SMEs: the role of network relationships in the entry to a psychically distant market. International Business Review 18(1): 50–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2008.10.002.

Oparaocha G.O. (2015). SMEs and international entrepreneurship: an institutional network perspective. International Business Review 24(5): 861–873. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2015.03.007.

Ozgen E., Baron R.A. (2007). Social sources of information in opportunity recognition: effects of mentors, industry networks, and professional forums. Journal of Business Venturing 22(2): 174–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2005.12.001.

Piantoni M., Baronchelli G., Cortesi E. (2012). The recognition of international opportunities among Italian SMEs: differences between European and Chinese markets. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business 17(2): 199–219. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJESB.2012.048847.

Pöyry (2013). Suomalaisen saha- ja puutuoteteollisuuden toimintaympäristön vertailu keskeisimpiin kilpailijamaihin nähden. [Comparison of the operating environment of the Finnish sawnwood and wood products industry with its main competitors]. Pöyry Management Consulting Oy/Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment of Finland. Loppuraportti. 56 p. [In Finnish]. https://zapdoc.site/tyo-ja-elinkeinoministerio-suomalaisen-saha-ja-puutuoteteoll.html.

Rangan S. (2000). The problem of search and deliberation in economic action: when social networks really matter. Academy of Management Review 25(4): 813–828. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2000.3707731.

Räty T., Toppinen A., Roos A., Riala M., Nyrud A.Q. (2015). Environmental policy in the nordic wood product industry: insights into firms’ strategies and communication. Business Strategy and the Environment 25(1): 10–27. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.1853.

Santos-Álvarez V., García-Merino T. (2010). The role of the entrepreneur in identifying international expansion as a strategic opportunity. International Journal of Information Management 30(6): 512–520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2010.03.008.

Schumpeter J.A. (1934). The theory of economic development. Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

Shane S. (2000). Prior knowledge and the discovery of entrepreneurial opportunities. Organization Science 11(4): 448–469. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.11.4.448.14602.

Shane S. (2003). A general theory of entrepreneurship: the Individual-Opportunity Nexus. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK. 352 p.

Shane S., Venkataraman S. (2000). The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Academy of Management Review 25(1): 217–226. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2000.2791611.

SME Sector Report (2017). Wood industry sector. Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment of Finland.

Statistics Finland. Structural business and financial statement statistics 2012–2017.

Toppinen A., Lähtinen K., Leskinen L., Österman N. (2011). Business networks as a source for competitiveness of the medium-sized Finnish sawmills. Silva Fennica 45(4): 743–759. https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.102.

Toppinen A., Wan M., Lähtinen K. (2013). Strategic orientations in global forest industry. Chapter 17. In: Hansen E., Panwar R., Vlosk R. (eds.). Global forest industry: changes, practices and prospects. Taylor & Francis Ltd.

Toppinen A., Röhr A., Pätäri S., Lähtinen K., Toivonen R. (2018). The future of wooden multistory construction in the forest bioeconomy – a Delphi study from Finland and Sweden. Journal of Forest Economics 31(1): 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfe.2017.05.001.

Vasilchenko E., Morrish S. (2011). The role of entrepreneurial networks in the exploration and exploitation of internationalization opportunities by information and communication technology firms. Journal of International Marketing 19(4): 88–105. https://doi.org/10.1509/jimk.19.4.88.

VTT (2018). Growth by integrating bioeconomy and low-carbon economy. Scenarios for Finland until 2050. VTT Visions 13.

Wood from Finland. http://www.woodfromfinland.fi.

Yin R.K. (2014). Case study research design and methods. 5th ed. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, California. 282 p.

Zaefarian R., Eng T.-Y., Tasavori M. (2016). An exploratory study of international opportunity identification among family firms. International Business Review 25(1B): 333–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2015.06.002.

Zahra S.A., Korri J.S., Yu J.F. (2005). Cognition and international entrepreneurship: implications for research on international opportunity recognition and exploitation. International Business Review 14(2): 129–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2004.04.005.

Zain M., Ng S.I. (2006). The impacts of network relationships on SMEs internationalization process. Thunderbird International Business Review 48(2): 183–205. https://doi.org/10.1002/tie.20092.

Total of 67 references.